|

4th President of the Confederate States | |

| Predecessor | Thomas Jackson |

| Successor | P.G.T. Beauregard |

| Vice President | P.G.T. Beauregard |

|

1st Vice President of the Confederate States | |

| Predecessor | Position established |

| Successor | Judah P. Benjamin |

|

C.S. Senator from Georgia | |

| Predecessor | Herschel Vespasian Johnson |

| Successor | John Gordon |

|

U.S. Representative from Georgia's 8th district | |

| Predecessor | Robert Toombs |

| Successor | John Jones |

|

U.S. Representative from Georgia's 7th district | |

| Predecessor | Constituency established |

| Successor | David Reese |

| Born | February 11, 1812 Taliaferro County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 1883 (aged 71) Richmond, Virginia, C.S. |

| Political Party | Whig (1836–51), Unionist (1851–60), Constitutional Union (1860–61), Southern (1876-83) |

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (born February 11, 1812 – October 14, 1883) was an American and Confederate politician who served as the 4th President of the Confederate States. He is also considered to be one of the founding fathers of the Confederacy, as well as the founder of the Southern Party.

Early Life[]

Early Political Career[]

Vice President of the Confederate States[]

Alexander Stephens was selected as the provisional vice president of the Confederacy and was later elected to a full term in the 1861 presidential election. He often clashed with President Jefferson Davis, disagreeing with Davis's policies such as the military draft that Stephens saw as tyrannical. Stephens opposed Davis's continued expansion of governmental powers during and after the war, a stance that would later lead him to form the Southern Party and run for president.

C.S. Senator[]

After leaving office as vice president, Stephens spent two years resting at home. He decided to run for C.S. senator in 1870, with the approval of the incumbent Herschel Vespasian Johnson. While in the Senate, Stephens mostly supported the status quo. He was privately against the Mexican-Confederate War, but he supported every measure put before the Senate that supported the war. Stephens recognized that the Confederate public wanted no part in political parties or political disputes in their post-war afterglow, and so he tried to remain quiet and unoffensive during his early years as senator. In 1873, he decided to run for president against Stonewall Jackson. He claimed that he was not running "against" the popular general, but actually running "alongside" him, as an alternative to the increasing power of the federal government and military. He published several editorials about his views and managed to win over some voters, but he never attacked Jackson directly. He won more electoral votes than expected but still didn't come close to winning the election.

As time went on, Stephens and other senators became more and more opposed to President Jackson's policies. The main breaking points were in 1874 when Jackson announced that he had successfully negotiated with the United States, securing a strong U.S. fugitive slave act, and in 1876 when he visited U.S. President Pendleton in Washington. In the months before his ill-fated visit, outraged Southern politicians urged the president not to go and "bend the knee to the North." When he actually appeared in public with the Northern president, the outrage was magnified. Only a few months after this incident, Senator Stephens and several other leaders like Robert M.T. Hunter and Vice President Albert G. Brown met and founded the Southern Party. By the end of 1879, most of Congress had joined this new party even while the old guard protested the very concept of political parties in the C.S.

Stephens was offered his party's presidential nomination in 1879, but he initially turned it down due to his declining health and old age. He was eventually convinced that the Southern Party needed its most popular leader to run as its first presidential candidate. He tried to campaign, but an illness sidelined him in September. He won a narrow victory over James Longstreet anyway.

President of the Confederate States[]

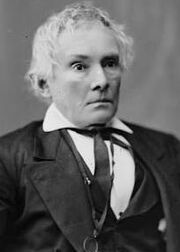

Stephens as President

At his inauguration, President Stephens promised to reduce the power of the federal government and the executive branch, and also reduce the size of the standing military. Backed by a Southern Party-controlled Congress, he was able to accomplish much of his agenda. Taxes were lowered, military men were sent home, military drafts were outlawed, settlement efforts in the Mexican territories were supported, and the institution of slavery was strengthened.

Unfortunately, Stephens continued to experience failing health all throughout his term. He was bedridden by mid-1883 and passed away on October 14, 1883 at age 71. He was the first Confederate president to die in office. His vice president P.G.T. Beauregard took over and went on to have a mediocre 2.5 years in office.

Legacy[]

While somewhat controversial in his time, today Alexander Stephens is universally recognized as a hero of the early Confederacy. He is remembered as the founder of the Southern Party, a party that still endures in the modern era. Since his death, Stephens has been heralded as a champion of limited government and Southern pride. Successive Southern Party candidates often tried to portray themselves as successors to Alexander H. Stephens. Stephens also appears on the Confederate five dollar bill.

| ||||||||||||||||||||