| The following page is under construction.

Please do not edit or alter this article in any way while this template is active. All unauthorized edits may be reverted on the admin's discretion. Propose any changes to the talk page. |

| Anna II | |

|---|---|

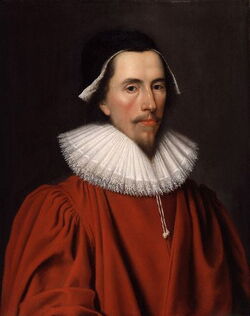

| Portrait of Anna II by Lucas Vergouwen (c. 1606) | |

| Portrait of Anna II by Lucas Vergouwen (c. 1606) | |

| Queen of Anglia | |

| Reign | 9th April, 1603 - 24th September, 1610 |

| Coronation | 1st August, 1603 |

| Predecessor | William IV |

| Successor | John IV |

| Born | 15th May, 1580 Ljouwert, Fryslân |

| Died | 6th June, 1643 Kassel, Hesse-Kassel |

| Burial | 9th June, 1643 St. Martin's Church, Kassel, Hesse-Kassel |

| Spouse | Johann of Katzenelnbogen |

| Issue | Ottolie William |

| House | Norfolk |

| Father | William IV |

| Mother | Catherine of Hesse |

The first real Queen Regnant of Anglia, Anna II was the last monarch from the House of Norfolk, itself a distaff branch of the originally Danish Estridsson dynasty.

Her reign, although short would be instrumental in defining Anglian policy for much of the 17th century. It saw intense political manoeuvering over Anglia's political and religious situation, a process which left her exhausted and would lead directly to her abdication.

Well-educated, and a talented scholar, Anna would preside over a flowering of culture in Anglia which had been left poor and isolated in Europe during the turbulent 16th century. She herself would write several widely distributed books during her 'retirement'.

Birth

Anna (or Anke, or Anissa) was born in May 1580, in Ljouwert, Fryslân, the eighth child of the then heir apparent, William of Durham, and third child with his third wife, Catherine of Hesse. Most contemporary reports suggest William received news of the birth of a healthy girl with 'good joy' some 20 kilometres away in the port of Harns on the morning of the 16th May suggesting Anna was either born early that morning or late the previous night, most historians agreeing she was born late on the 15th. William was about to embark on the reinforcement of his father's forces, currently campaigning in Suffolk and Essex and, despite the advanced state of preparations, he donated a barrel of beer from his flagship to the town so that her birth could be celebrated.

She would be baptised by Jemme Homminus, the Lutheran bishop of Groningen, on 12th September 1580 in a ceremony in the chapel of Ljouwert Palace. This was attended solely by a sprinkling of minor Frisian and Hessian nobles, amongst them her godparents, Anna van Egmond, William of Drenthe and Elizabeth von Dillenburg.

Early life

As both William and Catherine were Lutheran, and Anglia was currently in the grip of civil war between Catholic and Lutheran lords, Anna would be brought up within the confines of William's loyal territory of Fryslân. Her childhood was spent either in the grand hunting lodge at Oerterp or more usually at the royal castle at Ljouwert, and most early records of her refer to her as 'Anke of Ljouwert'. This did not change after 1590 when William ousted his cousin and Catholic rival Richard III and secured the throne. While William and Catherine moved permanently back to Anglia, Anna and her elder brother Henry of Ipswich remained in Fryslân.

The Frisian courtier Lieuw Huber described her as short, pallid, and frequently ill but 'possessed of a curiosity unmatched in the kingdom'. In 1586 she caught smallpox and narrowly survived, though she would be 'considerably' scarred by the disease.

Henrikus Jelckama, Anna's tutor

Charged with arranging the education of her two surviving children in Frisia before leaving to join William in Lincoln, Catherine of Hesse appointed the mathematician and astronomer Henrikus Jelckama as Anna and Henry of Ipswich's tutor. Whether a result of her natural thirst for knowledge or the talent of her tutor she flourished, understanding and debating the latest theories in various fields. By the

age of fifteen it was said she could speak Anglian, Frisian, three types of German (probably High, Dutch and Luxembourgois), Latin, Greek, Aramaic, French and Danish. She also took an interest in music, becoming proficient in the lute and virginals. It is generally accepted she was the best educated monarch of Anglia, at least since Henry III.

Succession

Despite William's considerable family only four of Anna's older siblings had survived into adulthood. The trauma of childbirth had killed William's second wife Margaret of Luneberg, and a daughter, Elizabeth, had been lost at sea in an ill-advised sailing across the Channel. The pool of heirs was further narrowed by William's second eldest son John publicly converting back to Catholicism and his subsequent campaigning for his cousin Richard III. Both John III and William would commit considerable time and effort striking whole swathes of their family tree from the succession, arguing treasonous sympathies, allegiance to the Papacy or dubious accusations of illegitimacy, an effort which culminated in the Act of Succession (1593) which legally placed a bar on Catholics inheriting Anglia.

The king and the Witenage considered this necessary to safeguard the status of Lutheranism in Anglia (and also make the massive strain and bloodshed of the previous decades worthwhile) but it considerably constrained the number of potential heirs. By 1600, following the death of Nicholas of Ely, Anna was second in line. A year later Prince Henry of Ipswich had died, leaving Anna as the sole Lutheran heir, her two younger siblings also having passed away in the 1580s. Anna was brought from Fryslân to Lincoln to be close to her father and there was tutored in statecraft by William's outgoing Chancellor, Christopher Mynn.

Mynn had retired from front-line politics ostensibly because of poor-health; he had suffered a wound in the Battle of Newark and by 1600 could walk only with difficulty. In a sense while Jelckama had tutored Anna to understand the natural world, Mynn taught her about the political one, imbuing her with a keen appreciation of Anglia's strengths and weaknesses and tutored her through the finer workings and rituals of the privy council and Witenage.

On 9th April 1603 William IV died. Anna wore mourning dress for much of the spring (at least until her coronation) but seemed more affected by the death of Mynn in November. The Witenage gathered in Lincoln three days later to exercise 'their right as electors' but Anna's succession was unanimously accepted. The privy council reconvened with William IV's favoured chancellor Thomas Finch at its head and the work of government began again. And it appeared Anna thoroughly understood the stakes. She had succeeded to an Anglia which was isolated in Europe, still wallowing in debt caused by war, famine and mismanagement and was still potentially religiously fractious.

Her coronation was on 1st August, 1603. An outbreak of plague in the summer threatened to disrupt proceedings but the population of Lincoln, indeed much of the County of Lindsey, thronged to see the twenty-three year old queen. Several poets left florid records of the coronation and descriptions of the young queen which verged on the fanciful.

Her reign marked the first time Anglia had been ruled by a queen regnant in her own right. Certainly, previous women had exercised power in Anglia; Laurette of Hainault wielded considerable power in the 1220s during the revolt against her husband. Elizabeth Betun effectively ruled jointly with William I during Henry III's period of insanity. Even her namesake Anna I, although titular queen for 24 years, only officially ruled as regent for her Danish relations Eric IX and Christopher II and exercised no power at all over Anglia's continental territories. Yet these women were not recognised by the entire Witenage and the full breadth of government power were withheld or were simply out of reach.

Anglia

Though the legacy of her reign would mainly affect the religious life of Anglia most of her original actions were driven by a desire to drastically improve Anglia's economic outlook. However this in itself would provoke dissent from the Witenage which was looking to change the relationship between itself and the crown.

In the main the Norfolk kings had treated both halves of the Witenage as a mere 'lower court' ruling through a small privy council. The Lords had been through wildly swinging purges throughout the War of Religion whilst under William IV the Commons had been shorn of its Catholic majority by natural attrition rather than coercion.

Religion

William IV had been very careful not to provoke Catholic passions considering they still made up a considerable percentage of Anglia's population, with some western and northern counties still mostly Catholic in the rural areas. While government had largely shifted into the hands of Lutheran ministers, out in the shires justice was dispensed by a mixture of Lutheran and Catholic judges and sheriffs, potentially open to accusations of favouritism or should they not act with absolute fairness. Perhaps misreading or ignoring this delicate situation Chancellor Finch thought that now was the time to push further, taking advantage of Anna's perceived popularity to argue for the dissolution of the remaining monasteries and chantries. This came at the same time as a new 'Book of Common Prayer' which was to be used at all services. This would backfire drastically and the Catholic lords in the Witenage all but revolted. Finch was told in no uncertain terms 'you may have won the war but do not assume you have won the peace'. Anna, coached from behind the scenes, forced Finch into a reversal and then effectively forced him out of power. She would then promote her favourite, Mynn's protégé, Henry Apethorpe, to the privy council and by 1605 he was in control of the government controlling access to Anna.

Henry Apethorpe

Henry Apethorpe, Anna II's most trusted advisor

The son of a baker from Ripon, Apethorpe had risen quickly within Mynn's household despite his lowly background. His keen mind had been recognised, becoming well-versed in the legal code of Anglia while he worked his way into politics after being made Exchequer of Kesteven in 1594. He had joined Mynn in Anna's household when she arrived in Anglia and assisted with her lessons in statecraft, the two soon becoming firm friends and allies. Therefore it seemed he was the natural choice to replace Finch after the Prayer Book debacle. Once Finch had been pushed out Apethorpe would largely backtrack on the attempted reforms.

The Common Prayer Book would still be implemented though much of the anti-papal language was largely removed from the litany. The still extant monastaries would continue but chantries were mostly shut in all but the most Catholic areas. Still, the quite formidable Catholic minority now felt as though they had been targeted and were now less willing to co-operate with government policy. To counter this he formed an alliance with the Speaker of the Commons, Edward Knole. Knole was a moderate Catholic (some might say crypto-Lutheran) and was distrusted by several lords in the privy council, however he worked effectively to pass laws and often roved instrumental in foiling Catholic plots against Anna. As a 'triumvirate', Anna, Apethorpe and Knole would steer Anglia into a short period of prosperity.

Woodcut from a pamphlet describing the events of the Newark Witch Trial

Aside from the wider Catholic vs. Lutheran issues in Anglia there was an increased number of accusations of witchcraft, events which excited public opinion and filled endless number of pamphlets. Whilst most ended relatively briefly some dragged on becoming sensations. Anna, despite her worldly knowledge was not immune from believing the tales either and, considering her bouts of illness, would often accept her courtiers' suggestions that malicious parties had set curses upon her. The most prominent case of her reign began in Newark in 1608 with the arrest of Gillis Smout who, her accusers alleged, had been responsible for several thunderstorms which had damaged buildings and crops. Under torture Smout confessed but also named numerous conspirators, and the pursuit and trial of all of these meant the case would not wrap up its findings until 1614. Anna even presided over several questions of the numerous accused and was said to 'be fond of prescribing the bridle (an instrument locked on to the head which held sharp prongs in the mouth preventing speech) until the truth could be gleaned'. Anna would in her retirement also write extensively on the subject, beginning with Daemonologie in 1615.

Frisia

Despite the fact Anna had been born in Fryslân and Frisian was her first language, her relationship with the county was occasionally fraught. This mostly revolved around the well-intentioned plan to integrate the county more within the Anglian realm which began soon after her formal election and coronation. Effectively the privy council simply wished the spending of the county to be reviewable by the Witenage in Lincoln and in return, space would be made in the commons for Frisian representatives. This they argued was necessary thanks to William IV's generous grants, in part of the county's loyalty to him and his father during the civil war period. Yet in practice much of this came from the royal purse not the witenage. The Frisian nobles feared their rights would be taken away and dug their heels in. The Frisian nobles, and indeed the Anglian kings, had enjoyed considerable freedoms without having to answer to a parliament of any kind. While the towns had little issue in sending representatives to Lincoln formally making the nobles and their lands open to scruntiny was a step too far. It was not helped by the fact Anna was frequently too unwell to visit the county in person, leaving the discussions to lawyers, who themselves were given little leeway by the privy council. Eventually in 1608 Anna reluctantly abandoned the effort.

Foreign Relations

Europe had spent the latter half of the sixteenth century dividing itself into heavily armed and mutually distrustful religious camps. The Holy Roman Empire itself had been divided following the First and Second Schmalkaldic Wars. Luxembourg had too become Lutheran, though had been wounded by the loss of Hungary and Bohemia and stayed aloof from the Schmalkaldic states due to long-standing disagreements with Denmark. Leifia too had only recently emerged from a corrosive religious war between Vinland and Álengiamark, a conflict which had shown that the enormously wealthy states of Iberia were only too willing to put aside their differences momentarily and use force on behalf of the pope.

In general Anglia's foreign relations were a mess thanks to the civil war. The Catholic kings had firmly cut ties with Kalmar whilst the Lutheran ones had broken links with the Holy Roman Empire. Although William had had no desire to get involved in German disputes he did want to secure alliances with individual Lutheran German states, most notably Hesse-Kassel. This led to marriage to Catherine of Hesse, and Anna's birth. Anna, slightly estranged from her mother considering the separation in 1590 relied more on the guidance of her privy council but relied on her familial connections to maintain the Hesse-Kassel alliance. Elsewhere the privy council was aware Anglia needed friends and this would be sought out in two competing ways.

Marriage

Anna's mother, Catherine of Hesse

Short, scarred from smallpox, and frequently ill, Anna did not cut a striking figure within the eligiable pool of European princesses. The future Gustav III of Svealand met her in early 1595 and apparently, and ungraciously, referred to her as the 'Frisian Mare' and the 'runt of the Anglian litter'. Her elder sisters had entered into marriage contracts across Europe but it seemed as though Anna would have to wait a while for her turn. As the pool of Anglian heirs narrowed however her hand was effectively worth more and Catherine of Hesse took control of her daughter's fate, or at least tried to. While she entered negotiations with several continental royal houses the Witenage and the privy council would decide the mater was far too important to leave to dynastic vissitudes. In March 1604 they began to increasingly isolate Catherine from her daughter couching it in terms of being for the greater good of Anglia. As time went on Anna herself found it politically expedient to also rebuff marriage proposals.

Whilst many in the Witenage wished her to marry to further Anglia's security within Europe, within her own privy council it was felt that her position was actually strengthened by not arranging a marriage or declaring an heir. Either option, they argued, had the potential to lead to a coup and Anna's (and their) probable replacement, imprisonment and perhaps even execution. However it is unclear whether this policy was a result of Anna's own position or a driver of it. By the evidence of her earlier life, and her post-abdication career, it seems unlikely that she flatly refused marriage for the sake of it. More likely she, and her mother, distant but continually writing letters, still held out for a grand alliance with another Lutheran kingdom.

Despite her championing of Lutheranism at home she was cool about committing Anglia's forces and its reduced treasury in foreign adventures for the religion. Overtures from Schmaldkaldic diplomats to join their alliance were quietly rebuffed though she maintained close relations with individual states. Luxembourg was quietly courted but again, no firm alliance was offered. It was simply enough for Luxembourg's ports, some the richest in Europe, to be open and receptive to Anglian shipping.

Trade

Indeed the privy council reoriented Anglia's foreign policy toward trade, or at least the desire to wean the country off a narrow fixation on the wool trade. The cross-channel export of wool had sustained the Anglian economy for centuries however the lustre was dimming compared to the more exotic goods now regularly appearing in the channel ports courtesy of Iberian, Leifian and Luxembourg traders. In 1604 Anna and the court would be approached by a company of merchants looking for royal protection for their new joint-stock company. Trading companies were not a new invention; Thorey IV had helped create a 'Northern Company' and a 'Southern Company' for Vinlandic merchants to pool their risks and vessels in the 1540s whilst Luxembourg had set up the joint-stock Flemish East India Company in 1599. Eager to emulate these examples Anna agreed to the creation of three companies; the 'African', tasked with muscling in on the spice trade out of West Africa; the 'Egyptian' tasked with handling silk and spices in the Mediterranean; and the 'Occidental' whose target was Leifian furs, Mexic silver and Carib tobacco. The crown granted each company a significant seed fund and took about 50% of all profits, a huge income for the country by the early 18th century.

The 'African' Company would flourish dramatically under Anna's successors, extending its remit to South-East Asia before declining in the 18th century. The 'Occidental' never really took off, as the Iberian states already controlled much of the trade. The 'Egyptian' however would prove durable, eventually branching out into the Baltic and still trades today.

Kalmar and Scotland

Anglia had had an awkward relationship with the Kalmar Union during the 16th century. The long period while the two followed different versions of Christianity had not helped and then Denmark's long-burgeoning distaste for Luxembourg made Anglia's incompatible with rejoining the Kalmar sphere. However Denmark was thoroughly engaged with German affairs and its Scandinavian partners were perhaps left to follow their own policies. Anglia therefore re-engaged with Scandinavia by simply avoiding Denmark. In this way it would renew friendships with Hordaland and Svealand whose interests avoided potential German pitfalls. Hordaland's Manx lands were important for Anglian defense while Svealand (and Saaremaa) were eager to improve their own trading links out into the Atlantic.

This would also see a certain degree of warming relations between Anglia and Scotland as the Scottish crown had passed into the Svealandic Leijonhufvud family in 1600. John IV's long minority gave Anglia ample room for manoeuvre and the potential to resurrect its old dominance north of the border. In April 1606 Anna was petitioned to assist in quashing the revolt of the Lowlands against the regency of John IV's father, John of Leijonhufvud, a revolt which soon aligned itself with the Stewart family who themselves wished to oust the Svealanders and reclaim the throne for themselves. Svealandic irregulars were already present but poorly led and not in enough numbers to secure the royal family's safe passage out of Scotland.

The lords in Anglia were unsure of how Wessex would react to such a move. Their spies had made it clear Wessexian money and arms had been flowing northwards and many felt that action in Scotland would provoke a direct war. Moreover, while they feared a defeat which could have led the exiled Richard III to reclaim the throne, they were afraid of what a war in itself might mean for Anna's health. She had been much distressed by the build up to war and it appears she often worked herself into a states of insensibility, states which she would apologise for later.

Apethorpe dismissed fears that this showed nervousness and a lack of stomach for war, writing to the Schmalkaldic envoy, Jens Maartmann, that

'her Highness wishes an intimate knowledge with every facet of our kingdom and though maintains the course of action is the best one, is much distressed by the knowledge at least some of our men shall be sacrificed for the cause. She questions the manpower and equip of every fort along our long borders as well as the armament of every ship in our dear navy. The incident [fit] of which you refer to is not a nervous compliant, this is an utter dedication to the preparedness for the worst of all possible outcomes, outcomes which she has already formulated, reckoned with, and dismissed.'

Despite Apethorpe's best protestations to foreign interests Anna was plainly ill during the 'Scottish Emergency', the Privy Council deliberately withheld certain facts, allowing Apethorpe or Knole to deliver them once danger had past.

In late May a large army was sent into the Scottish Lowlands to help bolster the royalist forces. Meanwhile the bulk of the Anglian forces were held back in Anglia itself, to protect Lincoln, or any other vital city, from attack. Dividing the forces was, of course, hugely expensive leading to a severe build up of debts with Anglia's German bankers but was deemed necessary. By leaving Wessex to make the first move it left open the possibility that Kalmar would be enticed to react. Spies, supposedly including the playwright Christopher Marlowe, made it clear both the Catholic Emperor in Vienna and the Papacy supported Wessex and for a nervy few weeks of 1606, while the Anglian forces fought successfully against the Scottish rebels, it seemed as though a general war would be imminent.

Indeed within Wessex anti-Lutheran passions were pushing opinions there toward war. Not only were the supporters of the ex-king Richard III in Wessex finding favour at court, but Thomas I seemed to be eager to renew the alliance with Scotland to help oppose Hordaland's ambitions in Ireland. The Wessex army under the Duke of Évreux crossed the Anglian border on 3rd June heading northwards, avoiding the main Jorvikshire towns to rendezvous with their Scottish allies. The main Anglian defending Lincoln under the Earl of Holland quickly reacted and the army was forced marched northwards to chase Évreux down. Évreux had warning that Holland was approaching however and the tired Anglians met a well-positioned force at Mæssham on the River Jore.

Évreux narrowly won the battle and Earl Holland was forced to retreat. However the advance toward Scotland had been disrupted and Anglia's militias in the south were being mobilised. Having been told not to act too rashly, Évreux abandoned the quick-march strategy and instead settled in for a more traditional attempt at grabbing Jorvik and holding the north.

This would give Holland the opportunity to rest and recover his forces. Évreux was driven away from the approaches to Jorvik in September by which point a battle between the Anglians and Leijonhuvuds and the Stewarts at Leith had defeated the rebellion in Scotland. However the presence of a Catholic force in northern Anglia had stirred passions and as the false rumour that Richard III had returned spread, there would be pro-Richard uprisings in southern Jorvikshire, Nottinghamshire and Ketteringshire. These revolts would be put down as Holland and Évreux fought their back toward the border and then on to Coventry in Wessex. The defeat of Stewart family had removed much of Wessex's motivation for war and Thomas I's diplomats arranged a peace before any dramatic losses could occur on Wessex's soil. And knowing what he did about Anglia's finances, Apethorpe was eager to accept it. It is entirely resonable to suggest that if Évreux had not been so cautious and had followed up Holland's army after Mæssham then the war could have swung in a very different direction.

The firm defeat of the Stewart family spurred a change in leadership largely weaning Scotland off its remaining Wessex alliance and normalised its relationship with its Kalmar neighbours, at least for now. And although Scotland would, in time, largely be cemented as a Calvinist kingdom then at least the Anglian ministers could content themselves that it was not Catholic. However the cost of the war, completely out of scale with its actual achievements left the economy shaky. This coupled with a famine in 1608 restricted the money Anna could spend on the kingdom. Poor relief was restricted, all court 'masques' were curtailed, no warships would be constructed for the remainder of her reign. Beyond the economic sphere focus returned to Anglia's Catholics and, more specifically, their loyalty.

Poland

Poland had been cultivated as a potential ally by William IV and Anna continued the wooing of the country. She would often write to its king, Wladyslaw IV. Wladyslaw would be much annoyed by Anna and her ministers' rigid focus on trade. Even so, Wladyslaw would propose a marriage in 1605, an offer which was eagerly seized upon by Catherine of Hesse but debated for four straight days in the Witenage. Of course in the end Anna politely declined the marriage, and avoided committing Anglia to any military adventures. The friendship was cooling anyway as Poland's focus shifted more to a Catholic alliance with Austria.

Caliphate & Iberia

The activities of the Egyptian company coincided with one of Morocco's periodic bouts of independence from the Caliphate. As Anglian merchants wished access to Egypt it began to supply the Caliphate with arms, especially cannon, and opened a consulate in Aleppo. This was in direct opposition to Castile, Naples and Arles who were haphazardly nurturing rebellious movements across North Africa and the shipping of the Egyptian Company was regularly attacked by fleets aligned to the Catholic powers. The Caliphate would even send a diplomat, Ibrahim Al-Ghazzi, to negotiate a firm alliance between the two against Naples. However Anna would abdicate, and Al-Ghazzi would die in St. Botolphs, before any treaty could be formalised.

Even without this formal alliance relations with Iberia remained poor. Competition over trade would push Castile and Leon into a state of undeclared war with Anglian shipping. This was certainly provoked by the decision to allow the navy to indulge in piracy against certain nations' shipping and in this there was a certain sense of encouragement from Portugal and Granada; both eager to maintain their respective holds on trade routes. While Anna perhaps avoided any repercussions from the policy it would lead to issues for John IV and V's regimes.

Later Reign

Edward Knole, Anna's Chancellor during the final years of her reign

Following the uprisings in Nottinghamshire and Ketteringshire there was a renewed effort to deal with the Catholic issue but Apethorpe was hesitant to repeat Finch's mistakes only a few years earlier. Rather than attacking the institutions directly, the Witenage passed the Recusants Act which banned Catholics from certain professions and legal rights unless they pledged an oath of allegiance to the monarch and not the pope. Anna was generally tolerant of any prominent Catholic once the oath had been declared however this only really applied to the nobility.

The economic effects of the Scottish Emergency put an immediate halt to any hopes of exploiting the general upturn in the economy for general benefit. And while the yeomen and nobles may have felt slightly better off than previously for the vast majority of the country it probably felt like a hard time to live through. There was considerable inflation in the latter half of her reign. The virtual eradication of poor relief plus the near-total closure of the traditionally charitable monasteries would have many of the poorest in society left on less sure sources. Begging, already an issue back in Henry IV's reign, was a much commented (and complained) upon issue and inevitably increased religious tensions as rural (and often Catholic) populations came into the more likely Lutheran towns.

Increasingly ill, Anna's actual involvement in the workings of government continued to decline. While the privy council, with Apethorpe and Knole at its head, continued to conduct much of the business in her place the monarch's apparent weakness led to the Witenage to exercise some of its long-lost powers once more, particularly with regards to scruntinising the kingdom's finances. This was aided by Apethorpe's downfall in the Spring of 1608 as Knole in general thought there needed to be a firmer balance between 'the queen, the people and the privy'. Apethorpe had built up a considerable personal debt having invested in a mismanaged scheme to drain fenland in Holland. His wife was then accused of sending letters to his creditors, threatening to use his leverage with Anna to ruin them. Anna immediately distanced herself from Apethorpe and he was soon pushed out of government.

Following this Knole was appointed Chancellor and convened the Witenage to attempt to gain further grants of taxation. Whereas Apethorpe's relationship with Anna could sometimes be described as over familiar, Knole took a more 'fatherly' approach and coached her through a dramatic address to the Commons. The so-called 'x Speech'... The speech failed in its aims to sway the Witenage's opinion however and the chamber was dissolved in October having failed to pass any of the proposed grants but, importantly, having extracted (or regained) the right to recall itself in the spring without expressly being asked for by monarch or chancellor.