The Celtic Church is a Christian sect created shortly after Doomsday. It is prominent in the Celtic Alliance, though it has begun branching out into other countries since the Alliance renewed with contact the rest of the world in 1992.

Post Doomsday

The various Christian churches became a useful tool in maintaining communication across the country in the aftermath of Doomsday. Nevertheless, the Irish Government, in its first emergency meeting, surprisingly disestablished its historical links with the Roman Catholic Church to ensure full freedom of religion in the North and to try to quell rebels there.

In the aftermath of Doomsday, the unification of many of the remaining churches has brought about the re-emergence of the Celtic Church. Until 1992, no contact with other religious leaders from outside the British Isles was possible and a redesigned and reformed church emerged from the isolation. The principle Primate of the Roman Church, the Archbishop of Armagh, placed the decrees of Pius XII as lapsed, since no communication was forthcoming from the appropriate corners, with similar beliefs being expressed by the Anglican community.

In addition, the General Assemblies of the remaining Free Presbyterian Churches and the State Church of Scotland met at an emergency joint session in Armagh. The overall General Assembly agreed to a text of unification, with the remaining Roman Catholic and Anglican dioceses, so long as their core beliefs were respected, though not without very serious dissent in some corners, especially from the delegates of the Free Presbyterian Church, not one of whom voted for it.

Unification

Emblem of the Celtic Church

The Synod of Armagh Easter April 22 1984: Tomás Séamus Ó Fiaich Primate of Ireland convenes the 1st Synod of the Celtic Church since Whitby in 644 with unification of the Christian faithful its first and only agenda item. The following declaration was signed by Tomás Séamus Ó Fiaich, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh, James G. Matheson, former Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, Henry Robert McAdoo, Anglican Archbishop of Ireland, and Gaetano Alibrandi, Papal Ambassador to Ireland.

Declaration of Armagh: "We the Christian faithful of the West rejoice and proclaim Christ at this our family unity. Sourced from pain and grief we embrace and celebrate our diversity and oneness. Let us proclaim with many voices in unison Christ be with me, Christ within me, Christ behind me, Christ before me, Christ beside me, Christ to win me, Christ to comfort and restore me.Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ in quiet, and in danger, Christ in hearts of all that love me,Christ in mouth of friend and stranger. We bind to ourselves today The strong virtue of the Invocation of the Trinity: we believe in the Trinity in the Unity The Creator of the Universe."

It was agreed that the new church would use a combination of the structure of the Presbyterian, Anglican, and Catholic Churches, in that the overall structure would be a mix of Anglican and Catholic styles, but new posts would be done much like the Presbyterian Church, with the local parishes getting to choose their own priest from those in the Church who are available when an opening occurs. Services would be High Anglican, with the Presbyterian simplicity put into the Churches themselves, where possible, with all the Catholic rituals in existence, but voluntary. Bishoprics and Archbishoprics would be held by the holders of such posts, who went along with the declaration, in all the Churches jointly, until they all retired and a new churchman could be appointed to the post that would be on their own and purely Celtic in faith. In most regards, it resembles what would otherwise be known as a "High Anglican" Church, with elements from both Scottish Presbyterianism and Catholicism.

Disagreement and Expansion

However, many did not go along with the Declaration. The more radical and conservative Protestants of the north, along with many Catholics, declined to do so, violently in some cases. The net result was the establishment of the Celtic Church, but with adjusted Catholic and Protestant hierarchies still intact. Motivation for the Protestants was obvious, given the years of trouble in Northern Ireland. Many Anglicans, or members of the Anglican-related Churches, simply dropped the their ties to the state, much like the American Episcopal Church did after the American Revolution.

These opponents, varying from the extreme radicals that acted violently in opposition to the declaration to the conservatives who simply opposed it, did not just roll over and accept it. As the IRA grew weak and disbanded, the Protestant organizations that had once opposed it with violence grew, taking up much the same role. However, general disillusionment with them, especially following attacks that they made, and a lack of funding and arms, had made them essentially powerless by 1992. Politically, however, there remains groups in the legislative body that are opposed to both the Alliance and the Celtic Church, largely from the conservatives.

For the Catholics, however, it was felt that the Archbishop was jumping the gun, so to speak, in many corners, leading to several Catholic bishops, led by the Archbishop of Dublin, Dermot J. Ryan, along with many of their priests, making what amounted to a schism in Ireland by refusing to go along with it. As a result, a Catholic Church structure remained after 1984, though it got weaker each year, as more came to believe that the Catholic Church was gone. For a short time, as well, the more radical members of the IRA, viewing this as a takeover of Ireland by the Protestants, continued to bomb the north, until Pressure from the Celtic government and a lack of both arms and funds forced them to stop. However, when contact with the world was restored in 1992, they were proven to be right, that it had remained intact. From there, it has rebounded.

Since 1992, the Celtic Church has bled members to some degree in its main territories, though they have canceled that out somewhat by expanding to other countries, largely inside of the British Isles but also to some degree elsewhere. Primarily, this means former France and Canada, though larger Congregations also exist in Africa and the ANZC, with smaller ones elsewhere. Also, before his death in 2003, Gaetano Alibrandi, the former Papal Ambassador and one of the signatures of the Declaration, renounced it, saying that it had been made in haste and in what amounted to a state of panic.

Partially as a result of this, in 2010 the Churches of Albion and Northumbria, in the English successor nations of Cleveland and Northumbria, approached the leadership of the Celtic Church with the hope of unifying into one church in 2020, agreeing provisionally with the context of the Declaration, which would bring back into the control of the church the Abbeys of Whitby and Lindisfarne.

Iona-Ì Chaluim Chille

Iona during restoration 1990

Iona (Scottish Gaelic: Ì Chaluim Chille) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland that is the home of modern Celtic Christianity as well as an important place in the history of Christianity in Europe and is renowned for its tranquility and natural beauty. Its modern Gaelic name means "Iona of Saint Columba". Due to its geography the Isle of Iona is once again plays a central role as a port and emergency landing for supplies to the Scottish fringe. In addition, the Celtic Church has re-appointed the 1st Abbot of Iona since 1498, the new Abbess is Naomh Bríd.

The main settlement, located at St. Ronan's Bay on the eastern side of the island, named Baile Mòr and is also known locally as "The Village". The new primary school, post office, the island's two hostels, the Abbots House and the restored Nunnery are here.

Iona Bay

The Abbey is a short walk to the north. Port Bàn (white port) beach on the west side of the island is home to the main freight terminal. Iona Abbey, is now the mother Abbey of the Celtic church, is of particular historical and religious interest to pilgrims and visitors alike from across the Celtic Alliance. It is the most elaborate and best-preserved ecclesiastical building surviving from the Middle Ages in the Western Isles of Scotland. Though modest in scale in comparison to medieval abbeys elsewhere in Western Europe, it has a wealth of fine architectural detail, and monuments of many periods and is one of the few remaining ancient buildings in Europe.

In front of the Abbey stands the 9th century St Martin's Cross, one of the best-preserved Celtic crosses in the world, and a replica of the 8th century St John's Cross (original fragments in the Abbey museum). The ancient burial ground, called the Rèilig Odhrain (Eng: Oran's "burial place" or "cemetery"), contains the 12th century chapel of St Odhrán (said to be Columba's uncle), restored at the same time as the Abbey itself. It contains a number of medieval grave monuments. The abbey graveyard contains the graves of many early Scottish Kings, as well as kings from Ireland, Norway and France. Iona became the burial site for the kings of Dál Riata and their successors. Notable burials there include:

- Cináed mac Ailpín, king of the Picts (also known today as "Kenneth I of Scotland")

- Domnall mac Causantín, alternatively "king of the Picts" or "king of Alba" (i.e. Scotland; known as "Donald II")

- Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, king of Scotland ("Malcolm I")

- Donnchad mac Crínáin, king of Scotland ("Duncan I")

- Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, king of Scotland ("Macbeth")

- Domnall mac Donnchada, king of Scotland ("Domnall Bán" or "Donald III")

In 1549 an inventory of 48 Scottish, 8 Norwegian and 4 Irish kings was recorded. None of these graves are now identifiable (their inscriptions were reported to have worn away at the end of the 17th century). Saint Baithin and Saint Failbhe may also be buried on the island.

Other early Christian and medieval monuments have been removed for preservation to the cloister arcade of the Abbey, and the Abbey museum (in the medieval infirmary). The ancient buildings of Iona Abbey are now cared for by the Celtic Church

Whitby/Lindisfarne

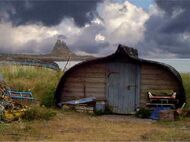

Lindisfarne in the distance with survivor camps

In mid 2007 a Celtic Church funded travel company based in Dublin begins approaching the governments of Northumbria and Cleveland with the hopes of starting pilgrimage visits to Holy Island (Lindisfarne) and the monastery of St Hilda's at Whitby due to there links to the ancient Celtic Church.

The monastery of Lindisfarne was founded by Irish born Saint Aidan, who had been sent from Iona off the west coast of Scotland to Northumbria at the request of King Oswald around AD 635. It became the base for Christian evangelizing in the North of England and also sent a successful mission to Mercia. Monks from the community of Iona settled on the island. Northumberland's patron saint, Saint Cuthbert, was a monk and later Abbot of the monastery, and his miracles and life are recorded by the Venerable Bede. Cuthbert later became Bishop of Lindisfarne. Recently Lindisfarne has become the centre for the revival of Celtic Christianity in the North of England. Following DD, Lindisfarne has become refugee centre, as well as pilgrimage destination.

In 2008 an expedition to London was undertaken to search the ruins of the British Library for the Lindisfarne gospels. Almost miraculously the gospels were discovered almost intact, there had been some water and light damage to the pages that had been open at the time of the DD attack, but after 18 months of restoration in Dublin by the conservators who worked on the book of Kells the book is due to be returned to the Lindisfarne church with great fanfare on the 2nd of May 2010.

Relations with the State

Since its inception as a republic the Celtic Alliance has made it clear to Christians that unification would be the preferred option as the state will have no dealings with disparate and arguing Christian factions, preferring only the one. Nevertheless, the republic proclaimed religious freedom through its constitution and accepted that not every Christian would follow the unified church. The Alliance is a secular state, officially, as a result, and many other churches remain preaching today in Alliance territory. Its following inside of former areas of France that are part of the alliance is minimal as well, though they did for a while depend on Celtic clergy for their services, along with several other areas of former France.

Structure

Structurally, the Church is much like the old Anglican Church, though it contains many more Catholic influences than that Church has had since its founding. Led by the Archbishop of Armagh, it has divided itself into the following dioceses and Provinces:

Province of Armagh

- Archdiocese of Armagh

- Diocese of Achonry

- Diocese of Clogher

- Diocese of Derry

- Diocese of Dromore

- Diocese of Elphin

- Diocese of Galway

- Diocese of Kilmore

Province of Cashel

- Archdiocese of Cashel

- Diocese of Clonfert

- Diocese of Cork

- Diocese of Kerry

- Diocese of Killaloe

- Diocese of Limerick

Province of Dublin

- Archdiocese of Dublin

- Diocese of Meath

- Diocese of Ferns

- Diocese of Ossory

- Diocese of Ardagh

Province of Glasgow, covering Scotland

- Archdiocese of Glasgow

- Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney

- Diocese of Argyll and the Isles

- Diocese of Brechin

- Diocese of Moray, Ross and Caithness

- Diocese of St Andrews

Province of Liverpool, covering England, Cornwall, Wales, France, and the Nordic Union

- Archdiocese of Liverpool

- Diocese of Besancon

- Diocese of Brest

- Diocese of Cherbourg

- Diocese of Holyhead

- Diocese of Lille

- Diocese of Penzance

- Diocese of Stockholm

In addition, the following dioceses, being small, are not under any province, but fall under the authority of the Head of the Church:

- Diocese of Ceylon, located in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, covering Asia

- Diocese of Delmarva, located in Easton, Delmarva, covering most of the former United States along with Mexico

- Diocese of Gambia, located in Serekunda, The Gambia, WAU, covering most of Africa

- Diocese of Jamaica, located in Kingston, Jamaica, ECF, covering the Caribbean and Central America

- Diocese of Jerusalem, located in Jerusalem, Israel, covering North Africa and the Middle East

- Diocese of Malta, located in Valletta, Malta, covering most of Europe

- Diocese of Newfoundland, located in Gander, Newfoundland, Canada, covering Former Canada, Alaska, and New England

- Diocese of Pelotas, located in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, covering South America

- Diocese of Tasmania, located in Hobart, Tasmania, ANZC, covering Oceania

Governance

When the Church was first founded, it fell to a joint leadership of the three signers of the Declaration. Since they retired, it has been governed by a member of one of the former Churches that signed the Declaration, with members of the other two being their deputies. When the head of the church retires, it passes to a former member of another branch, with the other two being his deputies, with the three former Churches taking turns at its head. As soon as the new Celtic Clergy are voted in, the arrangement will cease and it will from there on function like the Anglican Church did at the top. Heads of the Church have been:

- Tomás Séamus Ó Fiaich, James G. Matheson, and Henry Robert McAdoo, 1984-1985

- Tomás Séamus Ó Fiaich and James G. Matheson, 1985-1990

- James G. Matheson, 1990-1992

- Donald Caird, 1992-1995

- Thomas Winning, 1995-2000

- James Simpson, 2000-2006

- Robin Eames, 2006-Present

It is expected that the first purely Celtic Head of the Church will come to power at some point around when the Churches of Ablion and Northumbria merge with it in 2020.

Below the dioceses, the Church is governed on a model very similar to the Scottish Kirk system.

Worship

The Churches themselves in the Celtic Church function and preach today, in many ways, similarly to more conservative Anglican Churches from before Doomsday.

This has not always been the case, as for a number of years after the merging of the churches there remained several distinct branches to its operations. As new clergy were brought up through the new system, and the new schools for there training got going, this began to change.

It is estimated that purely Celtic services account for around half of services conducted in the Church today. The remainder have varying degrees of this in their services.

Overall, the Church has adopted the sacraments from both the Catholic and Anglican Churches. But, in a nod to the other branches of Protestantism, especially the Presbyterians, it is explicit that they are not mandatory, to the point where it is expressly stated in the founding church documents.

The basic rituals of the church, along with the environment and decorations in the churches themselves, have been scaled back as well, becoming far more basic.