|

25th President of the United States | |

| Predecessor | George Gray |

| Successor | Henry Cabot Lodge |

| Vice Presidents | Robert R. Hitt (1905-06)

Robert M. La Follette (1909-13) |

|

US Senator from Indiana | |

| Predecessor | William D. Bynum |

| Successor | James A. Hemenway |

| Born | May 11, 1852 Unionville Center, Ohio, US |

| Died | June 4, 1918 (aged 66) Indianapolis, Indiana, US |

| Spouse | Cornelia Cole |

| Political Party | National American |

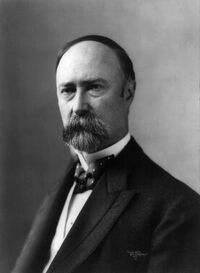

Charles Warren Fairbanks (May 11, 1852 – June 4, 1918) was an American politician who served as the 25th President of the United States.

Early Life[]

Political Career[]

After working as a journalist and railroad manager, Fairbanks was elected to the United States Senate in 1897. It didn't take long for him to increase his profile in national politics, becoming a candidate for president in the election of 1900. However, he was dismissed by most as still too inexperienced for the job, having been in government for only three years at that time. Joseph B. Foraker won the nomination.

The National American loss in 1900 allowed Fairbanks and his political allies to immediately begin preparing another candidacy for 1904. By the time the 1904 National American Convention rolled around, he was widely seen as the frontrunner, with his conservative ideas and his relatively fresh face in politics combining to make him an attractive candidate. His main competition going into the event was the progressive and charismatic Theodore Roosevelt, a representative from New York. The convention, firmly controlled by conservative delegates, gave Fairbanks the nomination on the first ballot. He feigned surprise at victory in his message to the convention and then went on to run a very traditional front porch campaign, while also continuing to work in the Senate. Going against President George Gray, who carried the legacy of the slain William Jennings Bryan's progressive ideas, Fairbanks campaigned on a message of returning to normalcy, both in society and economics. He pledged to boost the economy with protectionist policies to let it soar to new heights after the long economic depression of the 1890's, and also a return to the calmer politics of the 1800's, moving on from the progressive agitation of the recent past. Though Gray was just as much of a conservative as Fairbanks, it was impossible for voters to separate him and his party from President Bryan and progressive policies. Fairbanks won the presidency by a firm margin of 78 electoral votes and 4.6% in the popular vote.

Presidency[]

Backed by a National American majority in both houses of Congress, President Fairbanks set right to work in passing his protectionist economic agenda, instituting tariffs on foreign goods that he thought would propel the economy to heights it had not seen since before the Southern Rebellion. Tariffs were especially targeted at the Confederacy, which was experiencing a much worse and longer economic panic. Some at the time believed that Fairbanks was trying to continue to weaken the United States' southern neighbor in hopes that the nation would collapse and allow the US to regain its long lost territory. This never happened, and it is unclear if it was ever actually in Fairbanks' agenda at all.

Though it is unclear how much of it was directly due to his policies, the economy did indeed improve markedly under Fairbanks. The rise in the economy created general prosperity not seen in generations, leading to a renewal in the American spirit and a cultural renaissance of sorts. Many citizens of the time remarked that, for the first time since their loss in the war, it felt like America was truly a living country again, and not one trying unsuccessfully to move on from its depressing past. Fairbanks embraced the feeling of optimism and sponsored several programs meant to reward the creation of art and new architectural works, including successfully lobbying for a world's fair to be held in St. Louis in 1907.

With his country's economy and morale flying high at the end of his first term, it was expected that the president would easily win reelection in 1908. The only debate at the 1908 National American Convention was who would be nominated for vice president. Fairbanks' first vice president, Robert R. Hitt, had died in 1906, leaving the position open. Party leaders could not decide if they wanted a progressive or conservative in the role. There was still a sizeable progressive faction in the party, but Fairbanks' success had seemed to usher in a new era of conservative dominance, one that might be cemented further if the presidential ticket was entirely conservative. In the end, Robert M. La Follette, a prominent progressive from Wisconsin, was nominated.

The Democratic Party, briefly controlled by progressives again, put forth William Randolph Hearst as Fairbanks' opponent. He ran an energetic campaign, speaking all across the country, trying to link himself to the progressive legacy of President Bryan. Fairbanks, on the other hand, did virtually no campaigning, confident that he would win the election by a wide margin no matter what. La Follette, then, took up that task, traveling around much like Hearst in hopes of siphoning away progressive votes. In order to do this, he often spoke only for himself, rather than the conservative policies endorsed by the Fairbanks administration as a whole. This angered the president, who thought La Follette was trying to build up his own legitimacy by covertly challenging him, perhaps in hopes of a presidential run in 1912. This soured the two men's relationship from the beginning.

Despite the internal fracture, which was never revealed to the public, Fairbanks and La Follette won a landslide victory as expected, taking 306 of 356 electoral votes and 56% of the popular vote. From the beginning, La Follette was almost completely excluded from the Fairbanks administration and had little to no influence in the president's decision making. This led to him spending as much time as possible presiding over the Senate, a job that had been increasingly neglected by most vice presidents in recent decades.

The economy continued to roar in Fairbanks' second term, and this led to the president becoming less and less involved in policy affairs. He spent much of his time vacationing away from the swampy Washington heat and meeting with party leaders to discuss the 1912 presidential race. There were some who suggested that he should consider running for an unprecedented third term due to his impressively high popularity, but he disregarded such ideas as he was actually becoming quite bored with the job, longing to return to private life. With the incumbent president decisively out of the race, a long line of candidates lined up to run for both sides, or, rather, all four. Fairbanks was not especially interested in picking his own successor and so stayed out of the race, not making any endorsements as the National American Convention approached. The convention was dominated by a struggled between conservative and progressive delegates, with Theodore Roosevelt being the primary candidate for the progressives and Henry Cabot Lodge being the most prominent conservative candidate. When the progressives finally united on the 18th ballot to make a push for victory, Fairbanks changed his mind and decided to endorse Lodge for the presidency, sending in a telegram saying so before the 22nd ballot. This propelled Lodge to victory.

Fairbanks was content to stay out of the complicated and heated four-way race between his party, the Democrats, the Progressives, and the Socialists, but party leadership continually pressured him to help Lodge's campaign with statements and speeches of support. The president complied, releasing periodic messages to the public which reinforced his endorsement of Lodge, and he soon came to regret getting personally involved at all. When the results from the election came in, though, it became clear that his words might actually have been the difference between victory and defeat for his party- Lodge won only 19 more electoral votes than necessary to win an outright majority, propelled by slim victories in several key states.

Fairbanks retained almost all of his popularity all the way up to the end of his term, when he handed the job off to Lodge at the inauguration.

Post-Presidency[]

Fairbanks returned to Indiana, very happy with his presidency but eager to be home and have a free schedule again. His popularity remained high throughout this time, and he saw exuberant receptions in almost every town he visited. After almost a year of retirement, the former president followed in many of his predecessor's footsteps and returned to the practice of law, though the frequency of his cases was not high.

Fairbanks was generally supportive of President Lodge's entry to World War I in 1915 and also helped with recruitment efforts once the Confederacy declared war on the US in 1916. He did not live to see the end of the war, dying in 1918 at the age of 66. His funeral was as grand an affair as it could be during wartime, with thousands of Americans turning out to mourn the loss of their most beloved president in the post-war era.

Legacy[]

Fairbanks remained highly respected and liked by the public for several years after his death, but perception of his legacy began to change in the early 20's as more of the country turned to socialism. Socialists and leftists in general resented his presidency because of the era of conservative politics it ushered in, and also blamed him for the oppressive lack of workers' rights both during and after his presidency. When the socialists took control of the country after the Second American Revolution, his legacy was deliberately beaten down as a way to remove memories of America's capitalist past as its new leaders reoriented it in a different direction.

Taking a neutral view in the present day, most historians simply describe Fairbanks' legacy as "complicated." He was considered a great president in his time, probably the greatest in the post-war years of 1865-1928. His time in office saw a revival of the American spirit and, of course, a very productive economy. However, his conservative beliefs hampered the passage of many needed workers' rights reforms, leading a large portion of workers to radicalize and move away from the traditional parties they felt weren't helping them. This has led to both leftist and capitalist-oriented historians to see him as a negative historical figure overall, helping to start the downward trend of the country towards unrest and revolution, along with his predecessor George Gray. Some conservative historians, on the other hand, continue to praise his presidency, saying he did everything that could be expected out of a president- he maintained a great economy and lifted American morale. The mistakes which led to revolution, they contend, were made later on and had more to do with the refusal of American leaders to aggressively fight against socialist agitation, eventually leading to open revolt. These debates continue to rage on in scholarly circles, but to the average American, he is mostly just forgotten, overshadowed by the tumultuous 20th Century that followed him.

| ||||||||||||||||||||