| Anglian War of Religion (The Kalmar Union) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

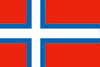

Romantic depiction of John III's landing at Harvik, May 1577 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John III Henry of Ripon | Richard II |

||||||

The Anglian War of Religion was a long period of civil war within Anglia which pitted the Catholic and Lutheran members of the Norfolk dynasty against one another for the future of their respective faiths.

Causes[]

Unlike his father, Henry IV had not really grasped the issue of the Reformation, he neither lent on the Lutherans as many of his advisors may have wished him to, nor had he allowed them free worship. The result was a quasi-official religion whose leaders were quietly emboldened by the lack of repression, unlike in Wessex where the two faiths would soon explode into war. Henry died a Catholic monarch but, having outlived all of his children, in his last year he lamented that perhaps God would not have taken them had he been more hard on the heretics.

Henry's younger brother, John of Northampton had succeeded him, crowned in 1563 in a perfectly Catholic ceremony but had, along with his sisters, Elizabeth and Estrid, undergone a secret conversion. In office his religious inclinations were kept quiet at first; a slow promotion of Lutheran, or Lutheran-friendly men to the privy council was all that really showed. The public conversion of several lords went unpunished and many remained in good standing with the king though overall he showed no particular preference to nobles of any one faith. His second marriage, to Antoinette of Auvergne in 1566, may have raised eyebrows considering that duchy's militant embrace of Lutheran faith, yet it was explained away as supporting Luxembourg's anti-French alliance.

John III

Richard II

In 1574 this balance was upset however, and the tension in Anglian society was definitively unleashed. In May of that year he set his privy council to work toward a Polish-style religious tolerance, enshrined in law. The Archbishop of Jorvik, Thomas Sampson, was instantly against the action, as were several of John leading ministers and his younger brother Richard of Jorvikshire. With a clear militantly pro-Catholic faction building at court the search for tolerance abruptly ended. At this point Thomas Sampson promptly died and, without recourse to Rome, John promoted a Lutheran, Edward Parker, to the post. The papacy complained of course, to which John expelled the papal legates and on the 6th of July made it clear he intended Anglia to be a Lutheran country.

John's move was perhaps perfect timing; Wessex was in civil war and could hardly raise any forces for the pope, Henry VIII of Luxembourg had also publicly converted ensuring at least for now there would be little foreign involvement; after all, every other state in Northern Europe had rejected Rome. However the pro-Catholic faction had grown, taking a majority of the Witenage and, with the pope's blessing, by the end of July had elected Richard of Jorvikshire as the rightful king, deposing the 'heretical' and 'poorly advised' John.

The War[]

John fled Lincoln as it erupted into riots and it was soon clear he could not rely on the militia there and rode south to Grantbridge where the forces of Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex could gather, and was soon joined by Archbishop Parker. Richard meanwhile had raised a force from Jorvikshire and the western counties and secured the centre of the country. The Lutheran forces however were either too disorganised or under-equipped and suffered a series of defeats. John and Archbishop Parker would eventually have to flee across the sea to Fryslân. John's eldest son Henry of Ripon attempted to hold Anglia north of the Tees but was outmanned and was captured at the Battle of Stockton.

Some now expected the war to follow the pattern of the Wessex War of Religion, however unlike Normandy, which was divided in its loyalties, Fryslân was united behind John and committed to its Protestant faith. Moreover the majority of Anglia's navy was, as Richard quickly found, Lutheran. Crews mutinied against Catholic captains, fired on their own ships and made sure John got to the continent safely. Richard would never be in a position to oust him from his Frisian stronghold.

Lutheran burnings in Jorvik, midsummer 1576

Henry of Ripon meanwhile had died in captivity at Jorvik in March 1575 having refused to recant. It was probably of natural causes but the rumour quickly spread that Henry had been executed without trial. Even as the militia of the County of Holland rose in revolt massacring the Catholic garrison at Lynn Richard seemed to embrace the rumour adding to the Lutheran fear of repression. The Witenage quickly passed laws banning Protestants from office and with little delay a purge of Lutherans or Lutheran sympathisers from public office began. Burnings of unrepentant Lutheran priests were introduced in late 1576 and these highly public events revolted opinion and further enflamed Lutheran dissent. Lutheran churches now read out the names of the 'martyrs'. Lutherans made up almost half of the population and even in supposedly staunchly Catholic Jorvikshire there was a considerable following. In many places worship in previously catholic churches was practiced openly. And while the vast majority of the population was not radicalized during 1576 there were three separate attempts on Richard's life as well as popular revolts in Norfolk and Dunholm which rumbled on into 1577.

Richard III

Bolstered by Richard's precarious position and spending most of his treasury on Hessians John stormed back into Anglia in the spring of 1577. A series of closely fought engagements ended in the Battle of Stamford on 8th June in which Richard II would die of wounds. However John's forces failed to follow this up successfully and though John would nominally reclaim the throne he failed to win Lincoln back and was pushed back to the eastern coast as a wet autumn gave way to an early winter. In Richard II's place came his son Richard III, quickly crowned by the still Catholic Witenage. Richard had none of the charisma of his father but was even more fervently Catholic. Brutal repressions quashed the rebellions simmering in the hinterlands and held John's forces to the Suffolk and Essex coast. A massive force of mercenaries, this time funded by promising 'futures' to several German and Italian banking houses delivered John decisive victories in 1580 which would briefly oust Richard and he fled into friendly arms in Catholic Wessex.

John III would die in Lincoln in October 1581 having spent a year unhappily attempting to restore his total authority and extract the money needed to pay his creditors. Shutting the Catholics out of the Witenage he attempted to rule through the privy council issuing the so-called Peace of Hykeham which promised equality and protection to both faiths. The Catholics were not convinced however and, as his mercenary force had disappeared earlier in the year, Catholic counter-revolts in Ely and Hertfordshire proved too much for him to put down. Once again Richard III could return from exile and took up the crown unleashing another round of violent repression against Lutherans before the restored Witenage begged him to ease up.

William of Dunholm, William IV

John's eldest surviving son William of Dunholm still held on to Fryslân and had made sure to forge links with Luxembourg and some German states, giving him access to diplomatic support and closing down Richard's trading options. While it was clear William could not afford to raise another invasion force just yet he instead made full use of the navy to frustrate Richard's attempts to gain the upper hand. Some ships would even be authorised to indulge in piracy against Anglian merchants. And despite Richard III's repression the Lutherans refused to convert back to Catholicism in large numbers. He had effectively bludgeoned them into an unyielding mass which would oppose his every move. When in 1589 a Catholic mob attempted to oust the Lutheran mayor of Norwich it was met with an even larger Lutheran mob which took over the city and sparked similar outbreaks of violence across the east and the north. It was a signal for all-out war to begin again. William of Dunholm had shrewdly built up a purse over the preceding years to pay for a war and now spent it launching his army in the Lutheran-friendly east. Over the next eight months there was near-constant fighting and a high death toll with losses of nobles on both sides. It ended however with William retaking Lincoln in April 1590, the Battle of Newark sealing the victory and Richard going into exile yet again.

Aftermath[]

William looked to resurrect his father's attempt at tolerance though public opinion had turned definitively against Rome and Catholicism in general. He resisted the knee-jerk removal of all Catholics rightly concluding that was his father's mistake in 1580, instead allowing the Catholics in the Witenage to 'follow their conscious' rather than forcing their resignation. By the middle of the following year the Commons would be 80% Lutheran and the lords about 50-50. The Act of Succession (1592) banned all Catholics from the throne, cutting half of his surviving children out of the succession and most of his cousins too in one stroke. It was followed by the long-promised law of tolerance: the Act of Settlement (1593) which confirmed Lutheranism as the state religion but gave assurances to protect the rights and land of Catholics. Revolts did still occur but William was absolutely strict on their suppression: loss of life was kept to a minimum. By the end of his reign all of the Anglian bishoprics would be in Lutheran hands and the largest monastic communities had been closed with their lands dispersed. There was the assumption that the smaller ones would wane away naturally, though as it turned out they did not.

Religious matters would continue to trouble Anglia through his daughter Anna's reign and, as Wessex had by 1580 bloodily rejected Lutheranism, the island was even more divided than before. The threat of Wessex, the Richardine branch of the family and some Papal-sponsored attack would define politics in the first decade of the 17th century.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||