| Mali Empire Manden Karufa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Motto: الناس الواحد، الدين الواحد (One people, One faith) | |||||

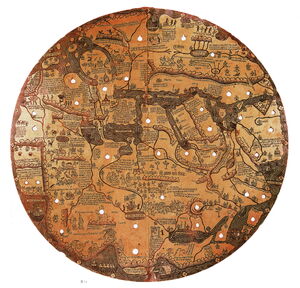

| Extent of Mali and its associated states in 1400

|

|||||

| Capital | Niani | ||||

| Largest city | Timbuktu | ||||

| Official languages | Mandé | ||||

| Recognised regional languages | Arabic, Tamashq, Igbo, Franconian | ||||

| Ethnic groups | Mande, Berber, Tuareg, Fula, Igbo, German | ||||

| Demonym | Malian | ||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (dumvirate) | ||||

| - | Mansa (Mali) | Uli II | |||

| - | Mansa (Bornu) | Dawud II | |||

| Legislature | Gbara | ||||

| Establishment | |||||

| - | Unification by Sundiata | 1235 | |||

| - | Somaoro deposed by Musa | 1315 | |||

| - | Ministry of Abu Yunus | 1352-1363 | |||

| - | Treaty of Kano | 1391 | |||

| Area | |||||

| - | Total | 3,300,000 km2 1,274,137 sq mi |

|||

| Population | |||||

| - | 1470 estimate | 24 million | |||

| Currency | Mithqal (MQL) |

||||

The Mali Empire (Mande: Manden Kurufaba, Arabic: أمبرتور ماندين / Imbrator Maandeen), also referred to as the Empire of Mali-Bornu or the Empire of Africa, is an imperial Muslim state in Sahel region of West Africa. It is the largest and wealthiest state in Africa, and enriched with cultural heritage mixed from both African, Middle Eastern, and West European origins.

Founded in the Mid 13th century by Mansa Sundiata Keita, the empire quickly grew to the height of its power under the reign of its most famous monarch, Mansa Musa I (1282-1346). After that point, the empire had a steady decline until the Treaty of Kano established after the Sefawa War (1386-1391), which established the nation as a Dumvirate between the Emperors of Mali and Bornu. The ruling dynasty, the House of Keita, has become synonymous with the Mali Empire, and the wealth of Africa in general.

History[]

Foundation[]

The name Mali loosely originates from an obscure Mande phrase meaning "place of the King". It most likely refers to a lost city that was the original capital of the Kingdom of Mali, the core state for the later empire. The Keita Dynasty, of obscure or even mytholgoical origins, rose to be the rulers of Mali after the collapse of the Ghana Empire in the 11th century AD. By 1180, much of the former core of Ghana had been reuinted by the Kingdom of Sosso under the Jarisso Dynasty. By the early 13th century, Sosso had subjugated the remnants of Ghana as tributary states. At the time, Mali was ruled by the King Maghan Konate (ruled c.1200-1218).

The founder of the Mali Empire was the Sundiata Keita (1217-1255), the son of Konate. Much of Sundiata's life is known by oral epic tradition, as is the case for much of Mali's history prior to the 1350s. After the death of his father, the Kingdom was ruled by Sundiata's half-brother Dankaran Touman (ruled 1218-c.1230), before being deposed and directly vassalized by the King of Sosso. Sosso went on to depose the Islamic institutions of Mali and revived the traditional African Paganism. This forced Sundiata into a period of exile, until he gathered enough support from elsewhere in Ghana to raise a large army against the King of Sosso around 1235.

The conflict against Sosso reached its climax at the Battle of Kirina in 1235, where Sundiata was victorious. All of the former vassals of Ghana and the allies of Sundiata pledged their allegience and suzerinity to Sundiata, which formed the first direct vassals of the Mali Empire. It was during this time that the original constitution of Mali and the Gbara were first formed. Sundiata used his affiliation with Islam, and the mythological connection to the companions of Muhammad, as legitimacy for the growth of his domains, with his conquests compared to that of Alexander the Great. It was for that reason that Sunni Islam played a key role in the legitimacy of the Keita Dynasty, up until the advent of Yunni Islam in the 1350s.

Sundiata spent the next few decades expanding the domains of Mali across the entire Niger delta, with the assistance of the generals that made up his direct vassals. Farouk and Fakoli led the southern campaigns that secured control over the salt and gold mines near Wagadugu. Tiramakhan led an impressive campaign westward, subjugating the King of Jolof which set the stage for the later conquest of Waalo by Abu Bakr II. Sundiata eventually died leading a campaign in the south, accidentally drowning while trying to cross a river.

Early Keitas[]

Extent of the Mali Empire at the time of Sundiata's death

After the generation of Mansa Sundiata, the series of rulers after him proved to be much less capable and were largely unable to maintain a stable state. His son Uli I (ruled 1255-1270) was immediately made Emperor, under the supervision of his Grand Vizier and older brother Manding Bory. Uli continued to conquer the Senegal valley, and created the precadent for every Mansa to make the holy pilgrimage or hajj to Mecca during his reign.

Once Uli I died, a power struggle ensued between various other sons of Sundiata. Wati was first given the throne and reigned from 1270-1274, during which time he constantly struggled for power against his brother Khalifa. In the midst of this unrest, the kingdom of Gao broke off as independent, and the capital city of Niani was left in chaos. After Wati died, Khalifa became Mansa and ruled for one year until 1275, during which time he was able to resubjugate Gao.

In general, Khalifa was known as immature and tyrannical, and was eventually deposed by the Gbara in favor of his brother, the Vizier Manding Bory. Bory changed his name to Abu Bakr I, and reigned from 1275-1285. Abu Bakr's reign was generally peaceful, able to re-stabalize the state but unable to make any new expansions. During these years of internal unrest and chaos, the finances of the empire suffered tremendously due to the lack of the Trans Saharan caravan trade.

In 1285, a former slave and prominent general named Sakoura siezed power and deposed Abu Bakr, one of the only interruptions there was in the Keita Dynasty. He managed to mostly restabalize the empire, and proceed on further conquests to centralize Mali, including the ancient kingdoms of Danakil and Takrour.

Sakoura is often depicted by later epics as a despotic tyrant, which is largely confusing his actions with those of his son Saomaro. Sakoura ruled over the capital and military of Mali with an iron fist, and kept body guards everywhere out of fear of being usurped again. Historians often judge his character as Machiavellian, almost paranoid, but certainly not tyrannical. He standardized the monetary system of Mali, and established alliances with both Egypt and Morocco in order to protect the Saharan caravan trade. In the 1290s, his vassals continued their eastern campaigns to subjugate the Niger region.

Sakoura was very respectful to the Keita Dynasty, and permitted them to retain a place of honor in Niani even while deposed. During this period of rule, the family of Kolonkan rose to power as most influential among the Keitas, descending from Sundiata's older sister. Much of this information takes place during the childhood years of Musa's epic, up until his eventual exile in 1298. Sakoura's eventual pilgrimage to Mecca took place in 1299, and was quickly followed up with a military expedition to the same region in Egypt. As the ongoing Nestorian Crusade was threatening to seize the Holy Land from the Mamluk Sultanate, Sakoura sent 3,000 troops to support the Sultan.

House of Kolonkan[]

The Great Mosque of Djeane was made during Gao's reign

Sakoura never returned back to Mali alive, but was murdered by his servents while crossing the Fezzen region of southern Libya. Tradition says that this was a deliberate act by the Bornu Empire, which eventually led to Mai Selma's deposition by Musa in 1329, but this is a very dubious story. As soon as Sakoura's caravan returned to Keita, his son Saomaro was deposed from power, and a swift revolt put the Keita Dynasty back in control, specifically the house of rulers descended from Sundiata's sister Kolonkan.

Sakoura had instilled great unpopularity among the nobles of the Gbara due to his attempts at centralization, so his death in 1300 saw the further decentralization and instability in the empire. Mansa Gao, that was chosen to succeed him, was known to be relatively weak and would permit the nobles to retain their autonomy. His relatively peaceful reign lasted from 1300-1305. Gao was, however, successful at creating reforms to improve the empire he had inherited. He restored the Saharan caravan trade, and created the first navy of Mali which was primarily based on riverine boats in the Niger and Senegal valleys. He also commissioned the Djeane Mosque, which was the peak of Sudano-Sahelian architecture before the African Renaissance. Gao's pilgrimage to Mecca occured from 1302-1303, in which he took the rest of the House of Kolonkan with him.

Gao was succeeded by his only son Muhammad I, who only regined for six months in 1305. After Muhammad's death, the throne passed to his uncle who was made Abu Bakr II (1305-1312). In spite of only reigning seven years, Abu Bakr's reign is especially well-known and esteemed by later historians. He is considered a capable ruler that kept the empire stable without gaining the reputation of a despot. He completed the construction of the Djeane Mosque in 1306, and retained the same financial policies of his predecessor. In 1307, Abu Bakr fully annexed the Kingdom of Waalo, which had previously been vassalized by Sundiata Keita. It was also during Abu Bakr's reign that the Hungarian explorer Aleksander Basic is believed to have visited Timbuktu.

Early Age of Exploration[]

Abu Bakr had a particular passion for the sea, and sponsored the first prototype of an age of exploration throughout the rest of his reign. The earliest ships of Mali can be best described as similar to Polynesian ships, being more advanced, larger riverine ships with very limited metallurgy. As Abu Bakr's reign is largely only known by later epics, the descriptions of his navy are often anachronistic and conflate it with the later navy made by Mansa Simba I. The navy we know about, that was used to chart the Western Sahara and claim the Gorgades Islands, is reconstructed via archaeology.

The explorations sponsored by Abu Bakr II were recorded in the epic of the Voyages of Sanbao, usually appended as a prologue to the epic of Mansa Musa. The three voyages of Sanbao were known to happen roughly from 1307-1310, and their descriptions are often filled with fantastic elements similar to those of the earlier Marco Polo or the later John Manderville. Some of the epic also draws elements from classical works on the same region, such as the Itinerary of Hanno of Carthage and the Geography of Strabo.

The First Voyage of Sanbao started in Waalo, and moved north hugging along the coastline to reach Morocco. Along the way, he stopped by the villages of Nwadibu, Eddaxla, and Guelmim. This created the first sea route to reach Morocco, although Morocco already had trade with Mali overland. This same route has been mostly used by traders to Europe ever since, although the expansion of the Sahwari Sidinate has made the voyage far easier.

The Second Voyage of Sanbao discovered the Gorgades Islands, although they were supposedly already known to the ancient Carthaginian Empire. The epic describes the islands was inhabited only by Gorgans, or demonic creatures from Greek mythology, and otherwise unclaimed. The four islands he visited are identified as Raee Jad (Boa Vista), Mar Yaqub (Santiago), Shaitan (Sao Nicolau), and Jadid Mina (Santo Antao). During his second voyage, Sanbao organized roughly 250 people to first settle these islands. The first ruler of the Gorgades, Omar, was said by tradition to be the son of Sanbao by a Gorgon.

The Third Voyage of Sanbao reached further beyond Morocco, and established direct contact with Europe. His journey through the Atlantic Ocean reached the islands of Bimbache (Hierro), Benahoare (La Palma), and Alfaar (Madeira). These islands were never settled, and eventually were annexed by Portugal. When he arrived on continental Europe, he managed to establish trade with both King Denis of Portugal and Ferdinand IV of Castile. It is from this initial diplomacy that all further interactions between Mali and Spain originate, and has contributed to Spain as being Mali's foremost trading partner in the Atlantic.

Saomaro's Coup and Civil War[]

Depiction of Saomoro in a mural dedicated to Musa

According to tradition, Abu Bakr's ultimate downfall came from a scandal immediately after the conquest of Waalo. Having recieved an oracle that visiting Waalo would ultimately lead to his doom, Abu Bakr stayed away from the front lines and only visited safer cities that were already integrated into the empire. It was during this visit that he was consumed with lust for Aresh, the wife of the soldier Djata. Abu Bakr ultimately raped Aresh and murdered Djata, where the only witnesses were his personal guards known as Manat and Uthman.

After the Sufi mystic Baobab exposed Abu Bakr's sin to the royal court, he was forced to abdicate and seek penance. The traditional legend of Abu Bakr's legacy is that he sailed off into the sea he so much adored, accompanied by Sanbao in one final voyage to seek the Mosque that lies on the far western edge of the world. Other versions of the legend describe him as a "sleeping king" legend, that he will one day return once the Mali Empire is ready for him.

Immediately after Abu Bakr's abdication, his son Mustafa was deposed in a slave revolt around the city of Niani, supported by Sakoura's son Somaoro. Somaoro was largely supported by the slave military that he recruited, which remained an important part of Mali's military until the reforms of Simba I. He never had direct power over all the empire, as the Gbara split into two factions that instigated the civil war. Gao also revolted at this point, to restore power to the Songhai Kingdom. Somaoro was paranoid on the possibility of being deposed by the Keitas just like his father, so he proceeded to have every single male in the House of Kolonkan brutally executed in his public court.

Somaoro was known by all accounts to be a wicked tyrant, and possibly the worst ruler in all of Mali's recorded history. The epics of Musa depict him as being the diametric opposite of the far more noble and pious monarch, but even archaeological evidence suggests this to not be an exaggaration. His enemies were skinned after death to decorate his court, with skin on his throne and bones on the doors. He even had a xylaphone made of bones that supposedly still exists in the Royal Museum of Niani. He was also described as a cannibal, and even forcefully fed human flesh to prisoners before their execution.

Musa I[]

The majority of the developments and modernizations of infrastructure, military, administration, and education in the Mali Empire as we know of it can trace their greatest development back to the reign of Mansa Musa I (1280-1346). His life and military exploits are detailed in the epics that bear his name, and are some of the most detailed historical descriptions of Mali at the time. His kind of hagiography tends to contain some embellishment or exaggeration of the original events, but still accurately depicts the cultural mood of Mali in his generation. By the end of his reign, Musa's military exploits had not only fully centralized the empire, but expanded their territories to their greatest extent.

Early Life and Rise to Power[]

Musa originally came from the clan of Abu Bakr, the brother of Sundiata, and thus set his family apart from the House of Kolonkan that grew in prominence at the end of the 13th century. His father, Fagelaye, had died while he was still an infant. According to his legend, Musa was originally unable to walk even in adolescence, and was forced to still crawl as a child until he was fifteen years old. Finally, in 1295 he succeeded to make his first steps, simultaneously rescuing his mother from public shame and showing up the Sons of Kolonkan that derided him.

Despite his royal heritage, Musa spent his early adult life as a cow herder, while also gardening his mother's fields of baobab plants. The epic of Musa describes his greatest feats of strength and wisdom, such as wrestling a lion with his bare hands at the age of sixteen. For his wisdom, the house of Kolonkan attempted to trick Musa into attacking a group of elderly women, who were secretly witches in disguise, but he acted in kindness instead. Finally, when he was eighteen years old (1298) Musa was forcefully exiled from Mali by the orders of Mansa Sakoura, being wrongfully charged on crimes he didn't commit.

While in exile, Musa gradually consolidated power for himself among the kingdoms of Upper Nigeria near Bornu, throughout the reigns of Gao and Abu Bakr II. After defeating the King of Gobir in a battle of wits to the death, he assumed control over that kingdom as his personal domain. He then moved to Daura, where he persuaded the king of Daura to adopt him as his legitimate son and royal heir, currently engaged to the Princess Aisha of Kano. He moved on from there to the city of Kano, where he accepted the marriage of Aisha in 1305. Finally, with the combined military power of Gobir, Daura and Kano under his personal demesne, Musa proceeded to consolidate power across most of Nigeria. He organized his own state in exile, with its capital at the palace of Daura that is still used by the Keita Dynasty to this day. He further organized his own army of Nigerians from various cities, as well as Mande soldiers who had fled the empire in sympathy with his exile.

Late depiction of the Battle of Mount Tabon

Balla Fasseke, Musa's cousin, eventually escaped from the court of Mansa Saomaro in 1315, and gave word to Musa that he should return to Mali to claim his throne in opposition to the tyrant. Musa was initially reluctant, but changed his mind when she presented baobab leaves from his mother's garden. Musa set out with his army first to Gao, where the king of Songhai pledged to ally with Musa against the greater threat. Musa's army at this point numbered as much as 30,000 troops, and set up defensive positions in Gao against the attempted counter-attack by Saomaro. Musa proved victorious at the Battle of Tabon Hill, where Saomaro's forces were largely decimated.

According to the legend, Saomaro managed to escape against any kind of direct attack or assassination using his sorcery, that allowed him to become transluscent or teleport. Belle Fasseke reported the secrets of this magic to Musa, and by exploiting its weaknesses Musa was able to finally put an end to Saomaro's powers and arrange for both his capture and assassination. Musa's army quickly encircled the city of Sosso, where Saomaro's remaining army was stationed, and forced them to surrender.

Early actions as Mansa[]

Musa continued to reign as Emperor from 1315 until his death in 1346. His first priority after defeating Somaoro was to reunify the Mali Empire after the chaos of the civil war. He pushed in western campaigns to subjugate the Kingdoms of Kita and Waalo, and reinstated the navy created by Abu Bakr II. The Songhai Kingdom revolted from Musa's authority in 1316, and was ultimately crushed by his army of 80,000 men in 1317. Although Musa wasn't personally present for the campaign, his general Ayyob utterly decimated the Songhai population, and completely displaced them from the region. Effectively, the kingdom of Songhai ceased to exist, and was partitioned by multiple neighboring vassal within the Mali Empire. Ayyob even order the individual houses to be broken down, and the people were forced to flee into the wilderness regions.

At the very beginning of Musa's reign, Western Europe was experiencing a great famine that severely depleted their resources and led to the death of millions. So Musa immediately exploited the salt mines in southern Mali, and massively exported these resources to Spain, Morocco and Egypt as a means to help releieve the famine. He re-established direct diplomacy and trade relations with the rulers of Castile and Aragon, and in 1317 he personally entertained a visit from King James II the Great. In 1318, he also further expanded relations into Italy by setting up trade with the Republic of Venice, and later with Milan in 1325. Relations were even established with the Papal States in 1330, although Malian historians always referred to them as the "Empire of Rome".

Interior of the Palace of Musa, the west alcove

His reforms to Mali's infrastructure are quite well known, in particular his restructure of the Gbara and local administration. He vastly expanded the major cities of the empire, which simultaneously created a greater sense of connection and unity between the various direct vassals. He created many new cities in between these regions, as well as the beginning of the imperial road system. Finally, Musa also created the first prototype education system with the first universities in Africa, specifically the Sakoura University and the Library of Timbuktu. Once Musa's main campaigns were completed in 1328, he greatly expanded the Library to include works from all across Europe and other trading partners, eventually amounting to over 400,000 books.

Conquest of Bornu[]

Mansa Musa conducted his campaign to conquer Bornu from 1319-1322. The exact reasons why he wanted to conquer Chad was never made completely clear. Later legends would say he was called to the campaign by a prophesy from Abu Yunus, who must have been a child at the time, if he had been born yet at all. Musa's speeches before Lake Chad pointed out the hostility Bornu had against the Keita Dynasty in the past, particularly the assassination of Sakoura in 1300, but this is also not verified.

Musa exploited the instability of Kanem's nomadic population to his advantage, by securing an alliance with the So people who invited him to occupy the city of Daniski. With one army stationed in this city and the other at his old capital of Daura, a flanking maneuver managed to crush the Bornu armies at the Battle of Hadijah, bringing a combined force of 75,000. By the beginning of 1321, Musa had captured the region of Lake Chad and positioned his armies outside of Njimi.

At this point, the Mai Abdullah of Bornu had been killed by an uprising of the So people, and his son Selma had seized power in his place. In hearing this news, Musa held an informal imperial court near Lake Chad, and made his first laws and proclamations in the presumption that he is the rightful ruler of Bornu to succeed Abdullah. In 1322, Musa laid siege to Njimi with 60,000 troops and forced Selma to surrender, and by doing so ceding the Empire of Kanem-Bornu to the Keita Dynasty.

Musa had a level of respect for the history and culture of the people of Chad, especially since he worked so hard to gain their trust in Abdullah's deposition. So rather than annexing Bornu directly, Musa established a personal union between the two royal houses, and forced the surviving members of the Sefawa Dynasty to intermarry with his immediate family in the Keita Dynasty. He established Njimi to be a secondary capital of the empire, and even after the Treaty of Kano it has remained a secondary political and cultural center for Mali ever since.

1320s[]

A late, but accurate depiction of Musa's Hajj into Cairo

Musa had, at this point, amassed an incalculable amount of wealth, both from his personal taxes, trade regulation, and gold bullion in vast quantities. According to many historical sources, Musa likely was the wealthiest individual in all of recorded history. So immediately following the conquest of Bornu, Musa sought to show off this wealth to the world during his pilgrimage to Mecca. Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca, and further itinerary across the whole Middle East, extended from 1323-1325.

This single event in Musa's reign is documented in more detail than any other event in his life, due to the vast amount of Persian and Arab historians who noted Musa's appearance in Mecca. He further traveled to Alexandria and Cairo in Egypt, as well as the cities of Aleppo and Tabriz in the fragmented Ilkhanate. He constructed his own Mosque in Baghdad, and donated a total of 200,000 Mithqals of gold to the Abbasid Caliph. Subsequent to this event, Musa generally retained a much more frugal policy towards his wealth of gold, in order to prevent the overall price of gold from decreasing too much.

After completing the campaigns to conquer the Kanem valley, Musa pushed for a southern campaign to fully subjugate the entire Niger River. This campaign lasted from 1326-1328, and established the southern borders of Mali that lasted up until the time of Mansa Mustafa. First he subjugated the Kingdom of Moss along the Ivory Coast, then he pressed further into Akan to subjugate the Kingdom of Bononam. After securing an alliance with the Ga people, Musa marched an army of 25,000 troops down the Niger River to the Benin Empire, and conducted raids that sacked parts of the city. At the end of this campaign, in spite failing to secure all of Nigeria, Musa nonetheless established a permanent trading outpost near Lake Kanji.

1330s[]

Picture of Hendrickus pisacus while writing a biography of himself

Future rulers of Mali would find it much more profitable to create secret alliances to establish a hegemony in Nigeria, rather than outright conquest. In the 1330s, the explorers Ahmad ibn Tulun and Muhammad ibn Ishaq frequently visited the court of the Aalafin of Oyo, allowing for the expansion of Islam and Mande culture into the nation. Musa overall held Oyo in high regard, where his third wife came from that royal court, where the other three wives came from Daura, Bornu, and Ethiopia respectively.

In the 1330s, Musa further managed to expand the trade network of Mali to the far east as well. Through his diplomacy across the Sahara caravan trade as far as Ethiopia, the Hindu-African Trading Pact was informally established, creating an "African silk road" leading from China to Mali. Historians debate on how official the "pact" ever was, but in recent years it was discovered at least one document from the Delhi Sultanate actually mentions Mansa Musa by name.

It was also in the 1330s that Musa entertained Hendrickus Pisacus, the Franconian explorer, who eventually converted to Islam and established the Saharawi Sadiyanate. He certainly is not the most influential of the Medieval African explorers, but he was definitely the most well-known in both Mali and in Lotharingia. Pisacus was initially forcefully removed from the palace of Musa and forced into exile from the capital, due to his mishandling of Musa's imperial harem. However, the event was later largely romanticized, and gave way to the traditional relationship between the Mansa and the Sidi ever since.

Ayyob[]

Succession Crisis[]

Originally, Mansa Musa's plans for his succession was to split his vast empire between his three surviving sons. Musa "the Younger" was given the title of Mali Emperor, while Ayyob was made the Emperor of Bornu, and Abu Bakr was made the ruler of Ghana. To soldify a smooth transition, Musa the Younger was made co-emperor with Mansa Musa starting in 1341. However, in 1346 Musa the Younger died a few weeks before Mansa Musa himself did, and did not leave much time for adjusting the succession. This left the empire in the hands of the half-brothers Ayyob and Abu Bakr.

Although Ayyob was of the Keita Dynasty, he was first made Emperor of Bornu in 1346 through the relation of his mother, Fatima Sefawa, and therefore established his position of power in Njimi. Initially, Ayyob proposed that neither brother should claim the title of Mansa until one of them dies without heir, effectively placing the empire into an interregnum. Three months later, however, Abu Bakr broke this agreement by marching 10,000 troops into the city of Niani, where he was proclaimed Abu Bakr III. This controversial act provoked the start of a civil war in Mali, that lasted from 1346-1350.

Although there is no epic on the life of Mansa Ayyob, the details of this civil war were compiled through the history of Mali trasmitted by Ibn Battuta, who visited the empire in 1351. The initial phase of the war forced both sides to consolidate their respective centers of power in both Ghana and Bornu, as there was no clear geographical divsion between the two factions. Abu Bakr eventually managed to subjugate Waalo after a series of battles, which accidentally led to the sacking of Dakar in the Great Fire of 1347. Ayyob managed to seize control over the Nigerian frontier, defeating a local Igbo revolt at the Battle of Zaria with 8,000 troops.

Abu Bakr pushed east in a concerted effort to destroy Ayyob head-on, and scored initial victories while invading Songhai with 28,000 troops. Ayyob utilized more advanced, unconventional tactics at the Battle of Gao, including the adoption of gunpowder from Europe, and ultimately defeated Abu Bakr with a considerably smaller force of 25,000. Abu Bakr was forced to retreat back to Macina, looting various supply depots along the way. After a long campaign by Ayyob to invade the western empire, he eventually succeeded to capture Macina in 1349, and proceed from there to secure control over the entire Sengal valley. Late in the year of 1350, Niani itself was sieged by Ayyob, during which time Abu Bakr was killed by city archers. Ayyob would continue to reign unchallenged from 1351-1368.

Sole Monarch[]

Interior of the Nabi Yunus mosque, final resting place of the Propeht

Much of Ayyob's reign after this point was devoted to the reconstruction and stabilization of the empire, and restoring all their profitable institutions left over from the reign of Mansa Musa. It was for this reason that Ayyob did not make any signficant campaigns of his own, although the Qamarid Dynasty would proceed to conquer Jabal Asada and Bononam for the empire. Although destructive on the whole, in a way the civil war saved Mali from suffering any significant losses during the Black Death, which had swept over Europe and the Middle East from 1346-1353.

Becuase Ayyob's reign was largely peaceful, he is best remembered as a great patron of the arts and sciences, as well as a respectable philosopher in his own right. It was during his reign that the artistic style of the "Sahelian Gothic" first emerged, and continued to flourish with the adoption of Yunni Islam. Works of literature, enshrining the epics of Sundiata and Mansa Musa, also trace their origins to this generation. Ibn Battuta, the world-famous Moroccan explorer, visited Mali from 1351-1353, and documented much of their recent history, culture and religion at the time.

Ayyob had a desire to expand the empire further south into Africa, and managed to secure this goal in only limited ways. The local feudal noble named Baraq Al-Shams led campaigns to conquer the rest of Jabal Asada and Bononam, establishing the secondary port cities of Koya and Nkore. This campaign utilized 14,000 troops and lasted from 1352-1355. In the same year of 1355, Ayyob first established the tributary system of Nigeria which extracted a regular supply of slaves from the region.

This generation is most famous for the miraculous conversion of the empire over to Yunni Islam, championed by the Prophet Abu Yunus (c.1318-1363). Yunus began preaching his public ministry in 1352, and quickly gained a large following of disciples from his preaching and reported miracles. His hagiography typically describes this as a great revolution of religious innovation. However, the contemporary writings of Ibn Battuta describes the culture of Mali as already being similar to what Yunus preached, suggesting that his ministry only served to codify or justify what the Mali Empire was already doing.

From 1358-1359, Abu Yunus would appear in the royal court and the Gbara, sharing his prophetic visions and theology. According to his hagiagrophy, Yunus convinced the Mali Emperor and the court of the Gbara by divine miracles. However, it also seems likely that Ayyob had many political reasons to change religions as well, such as the asimilation of African cultures in the empire internally, and the severance of ties to the Abbasid Caliphate externally. When Yunus eventually died in 1363, his successor Idris Al-Segu was named as the first Manding Caliph, which has remained the nominal head of the Yunni religion ever since.

Decline[]

Mustafa[]

The death of Mansa Ayyob is usually considered to mark the end of Mali's Golden Age, and the subsequent years of the empire saw the gradual loss of the territories Musa had gained. Mansa Mustafa succeeded his father's office without issue, and continued to rule from 1368-1386. Mustafa's personality is considered a complex mix of determination and paranoia, and many historians have theorized if he had a mild case of autism. He has no epic tradition to his life, which has served to prevent his personality from being veiled in the same levels of propoganda that his predecassors had.

Around the time Mustafa ascended to the throne, the Franconian immigrants led by Hendrickus Pisacus had settled the Saharawi Sadiyanate in the Western Sahara, establishing the prosperous port city known as Samla. Mustafa's first act as Emperor was to invite Pisacus' son Mikhail to the court in Niani, and use him as leverage to secure the complete vassalization of the Sidi. The Sidinate after this point would become one of the largest ports for Mali, especially after the loss of the southern territories.

Mustafa's paranoia caused him to alienate the more powerful members of his court, out of fear of facing another civil war like his father had suffered. He placed his brother Dawud in charge as the Regent of Bornu, effectively the same title that Ayyob was given twenty years earlier. However, he greatly restricted Dawud's abilities and priveleges as the ruler of Bornu, in an attempt to prevent him from usurping the throne. Late in his reign, Mustafa also threatened war against Ethiopia if they did not withdraw from the Egypt-Ethiopian Trade War.

In the south, Mustafa's greatest rivals were the allied vassal states of Jabal Asada and Futa Jallon, ruled over by Yaqub Al-Shams and Umar Al-Qamar, respectively. Yaqub was the son of Baraq Al-Shams, who had gained effective power over most of the southern territories through his military conquests. Just like in Bornu, Mustafa imposed heavy restrictions on these nobles in an attempt to prevent their uprising. Not only was this measure ineffective, but it prompted Yaqub and Umar to join in a military alliance against the emperor, which eventually formed into a personal union in 1371.

Mustafa was afraid this Qamar-Shams union would threaten his control on Bononam, the last imperial territory in the south. So he attempted to fully annex the state in 1373, which ended in disaster. The native Bono people, led by Addas Al-Ubiat, staged a slave revolt to remove the emperor's control over the region. This led to the Bono War from 1373-1375, where the Qamar-Shams union intervened to annex the Bononam state for themselves.

Successor states of Mali after the Bono War

The most defining moment of this conflict was the so-called Fatima Campaign, where the general Yahya Al-Shams executed an invasion of the Senegal valley that sacked the city of Segu. According to an apocryphal legend, this campaign was instigated by the Mansa capturing Yahya's wife, named Fatima, and holding her imprisoned in Segu. After the disaster of the Fatima Campaign, Dawud of Bornu threatened to intervene in the conflict unless the Emperor negotiated for peace. So at the conclusion of the war, the states of Qamar-Shams would cede permenantly from the empire, while techncially still acknowledging Mustafa as the emperor. This has defined the southern border of Mali ever since.

Sefawa War[]

Just as Musa and Ayyob both nominated their successors before their death, Mustafa also nominated his son Simba to succeed after him, and elevated him to Co-Emperor in 1383. Simba had spent much of his life studying in Europe, where Mustafa sent him in 1369. Simba had studied extensively in both history, science, tactics and philosophy from various cities in Europe, including Florence, Rome, Constantinople, Paris, and Brussels. By the time Simba became Co-Emperor, he had amassed considerable knowledge and background in western culture, which he had attempted to impose in Mali throughout his reign. After Mustafa's death, Simba effectively ruled from 1386-1399.

After Mustafa died under mysteroius circumstances, the Sefawa-Keita War continued from 1386-1391. According to Malian sources, Mustafa was assassinated by his brother Dawud while on a hunt, but according to Kanem sources he was killed by Simba. The Sefawa-Keita war effectively split the empire on a variety of issues. The Chadian and Mandike people had different languages of course, but their religions were also divergent at this point, as Bornu still held to Sunni Islam whereas Mali changed to Yunni Islam. The Abbasid Caliph's call of heresy on Mustafa in 1386 might also have contributed to this religious divide.

But the most divining division of Mali, of course, was the political rift between the dynasties of Keita and Sefawa. Although Dawud and Simba were both of the Keita Dynasty, Dawud's maternal ancestry placed him closer to the Sefawa lineage, due to the intermarriage encouraged by Mansa Musa. Furthermore, Bornu's patriarchal succession ensured that Dawud should succeed Mustafa as the eldest male in the family, whereas Mali's primogeniture passed the throne to Simba.

Contemporary portrait of Mansa Simba I

Simba had initally desired to lead a direct campaign for the invasion of Bornu, but this was delayed by a number of issues. First Simba focused on reorganizing and purging the military for any possible descent. Then, in 1388 the Songhai people revolted again against Mali. Unable to deal with Songhai's belligerance any longer, Simba ordered their entire culture to be exterminated. Simba had such an obsession with wiping out the Songhai kingdom, in fact, that this placed a significant drain on his resources, robbing him the opportunity to conquer Bornu when he had the chance.

Dawud took the initiative to lead a southern campaign, sizing control over all of Mali's possessions in the Upper Niger region. This eventually led to the Siege of Abujah in November 1390, which was a Bornu victory. At this point, it seemed that Dawud would be able to fully encircle Simba's troops before he had a chance to leave the Songhai region, which would have given Dawud a victory. However, in 1391 the government Dawud had left in charge of Njimi had collapsed, and the entire Bornu Empire was in danger of falling apart. Dawud had attempted to replicate the government of Mali in Njimi, using the same system of Sundiata's constitution and the Gbara, but this ultimately proved ineffective to keep Bornu stabilized.

The simultaneous military defeat of Simba and the collapse of Bornu's government caused both sides to recognize the conflict as a stalemate, and worked out a new executive constitution of government which is now known as the Treaty of Kano. The effect of this treaty split the empire into two separate nation states, with their own monarchies, but both organized and legislated by the same Gbara council. The political organization agreed on in the Treaty of Kano has remained the effective form of government in Mali ever since.

Under the Treaty of Kano[]

Simba I[]

Depiction of the voyage of Abu Ismail, admiral of the Malian fleet

The remainder of the reign of Mansa Simba I was focused on the reconstruction and revitalization of the Mali Empire. However, for Simba this revitalization was not merely a carbon copy of the empire of Mansa Musa. Rather, Simba had a vision of fully modernizing the empire to meet the standards of Western Europe, while at the same time creating their own style unique to West Africa. He overhauled the military, drastically reducing their size to a manageable elite core that could be better trained and equipped. He also standardized Mali's education system, building on the earlier work of Musa.

Most significantly, Simba I focused on expanding Mali's domination of the Atlantic Ocean. He upgraded and expanded the ports of Dakar and Samla, and instituted the first proper naval academies there. The Dakari Atlas, published in 1395, perfectly depicts how the world looked like at the time of Simba's reign, while also showcasing the cartographical art typical of the Sahelian Gothic. This expansion into the sea would become the main focus of subsequent rulers of Mali. As the nations of Spain, Lotharingia, Portugal, and the Hansa began creating trading posts and minor colonies across the western coast of Africa, the Mali Empire would supplement their own navy by purchasing from these European powers, in exchange for lucrative trade deals.

Musa II[]

Simba died without any surviving sons, so the Empires of Mali and Bornu fell back into a personal union, ruled by Mansa Musa II (1399-1427). As the nation was tired of war at this point, Musa respected the terms of the Treaty of Kano and did not make any attempts to integrate the two empires back together. In fact, late in his reign he ceded the Bornu Empire completely to his cousin Othman, who became the first restored Sefawa ruler of Bornu since the conquest of Musa.

The Libyan Crusade

Musa II's reign is probably best well known for the works of literature and poetry that he patronized, building off of the literary tradition started by Ayyob. This was the time that the epic stories and hagiographies of people like Sundiata, Musa I, Sanbao, Abu Yunus, and Simba I were all codified and published in the form that we now know of them. As a result of this, there is very little documentation or discussion on the personal life or personality of Musa II himself. Instead, Musa preferred to be depicted in the style and image of the stories he patronized, both in art and in literature.

It was during Musa's reign that the Libyan Crusade took place, in which a German colony existed in Libya for almost a generation. This was key in expanding Mali's carvan trade more directly to the Mediterranean, including the exports of African slaves. Even after the loss of Tripoli in the Barbary Crusade, Mali was still able to export sufficient slaves for the use of Portugal and Lotharingia's plantation colonies. The Kingdom of Tripolitania was also significant by being a staging point for the French explorer Roger Cartier, who became the first French man to visit the Mali Empire. Even so, Musa was greatly concerned how an invasion of Crusaders could disrupt the carvan trade in North Africa, and so he formed a loose military alliance together with the Maranid, Hafsid, and Mamluk Sultanates.

In terms of the navy, Musa II began by restoring the existing Malian colony in the Gorgades Islands, which had now existed for exactly one hundred years. He created a separate system of the government to organize naval operations and future colonization, given to his minister Dhul Al-Kilfi. The voyages of discovery during Musa's reign established trade routes to the southern independent states of Jabal Asada and Nkore, and eventually discovered the islands of Ya Sin, which were later renamed to Sao Tome and Principe.

Mohammed II[]

While Mali was pushing to expand their influence overseas in Africa, Europe was pushing to expand their influence in Mali. The Lotharingian West African Trading Company first arrived at the borders of Mali by the expedition of Egbert de Leeuw in the early 1420s, by following the routes described in the writings of Hendrickus Pisacus. Lotharingia referred to the empire as the Ryk de Musa or "Empire of Musa", but it's not clear if they named this after the current ruler (Musa II), or the empire's main founder (Musa I).

Franconian explorer Isaac Alef Vletcher in the court of Mansa Mohammad II

In 1427, Musa II died and was succeeded by Mansa Mohammed II, who reigned from 1427-1448. Mohammed II was far more savvy in his negotiations with Europeans, and frequently played the colonial powers off of each other for better favor. This was most apparent in one anecdote dated to 1429, when Mohammed entertained both Isaac Alef Vletcher from Lotharingia and Mario de Velencia from Spain at the same time. In 1437, the Portuguese explorer Alfonso Baladia was accidentally stranded in the Sahwari Sidinate, and was eventually returned home by Mohammed's intervention.

Administration[]

Dual Mansas[]

Mali is an absolute feudal monarchy, with the head of state known by the title of Mansa, or Emperor. Since the founding of the Empire by Sundiata, the royal lineage of the Mansas traces back to the Keita Dynasty, descending from the common ancestor of Sundiata's father Konate. The House of Keita extends across various other feudal titles in Mali, which are all universally respected by their kinship to the royal house. Ultimately, the Keita Dynasty traces its roots back to Bilal ibn Rabah, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad.

Originally, the Emperor of Mali also ruled over Bornu and Upper Nigeria in a despotic personal union, consisting of the nations that Mansa Musa I subjugated in his eastern and southern campaigns. After the conquest of Bornu in 1328, the Sefewa dynasty was heavily married into the Keita dynasty, which split off again after the Sefewa War in 1386. As such, the Sefewa Dynasty also is treated with the similar respect as Keita, while in the Kanem region.

Under the Treaty of Kano, the single Empire recognizes two imperial states under the same government, Mali and Bornu. The Mali state has the residence and court of the emperor located in the city of Niani, within the traditional Kingdom of Mali, while the state of Bornu has their imperial court in the city of Njimi near lake Chad. A third summer palace, built by Musa before he became Emperor, exists in the city of Daura. These two states are effectively independent of each other, but organization and administration is always coordinated through the same legislative body, the Gbara.

Mali's emperor is succeeded via direct primogentiure, but an heir apparent must always be recognized. In Bornu, the Mansa is succeeded by patriarchal succession. Each new Mansa must be approved by both the Caliph and the Gbara.

Gbara[]

The Gbara, or Great Assembly, is the head of the government for both Mali and Bornu, and acts as a legislative body composed of feudal nobles. Sundiata first commissioned the charter for the organization of the Gbara, which also outlines the rights and responsibilities for all the citizens of the empire. This charter is known as the Kouroukan Fouga, which was orignally passed down orally before being officially published by Mansa Musa.

The offices of the Gbara, which also correspond to specific noble houses, are assigned by the charter specific tasks and responsibilities to maintain throughout the empire. Originally, these offices were held by clan leaders within traditional tribalism known to the Manding people at the time of Sundiata. Under the adminstration reforms of Mansa Musa, this was transitioned into more abstract feudal titles that were no longer clan-based.

The 32 permenant members of the Gbara are divided into four committees: sixteen oversee military, called the Tontigi, four manage administration, called the Maghan, five organize education, called the Morikanda, and seven regulate the economy, called the Nyamakala. Additionally, a second house of rotating offices represent the general body of feudal titles across the entire empire. The Gbara can meet in any city, and alternate between the courts of Niani and Njimi, but most commonly are stationed permenantly in Kano.

Local Administration[]

The subdivisions of the Mali Empire

Despite being run under an absolute monarchy, Mali traditionally is very decentralized in its power. Local nobles act as direct vassals to the emperor, and are all traditionally sworn in allegience to the Emperor and the Gbara in an oath since the time of Sundiata. However, individual nobles have full autonomy in raising and regulating local taxes, as well as raising their own levies and military for their own purposes. As such, much of Mali's territorial expansion was owed not to the imperial miltiary, but rather to local vassal nobles.

Each of these vassal nobles are referred to as either by the title Mai (King) or Amir (Prince). Collectively, the vassal government of Mali is known by the Mande term dyamani-tigui. Generally speaking, Mali prefers to appoint native rulers as vassals instead of placing it under foreign rule. However, regions that are conquered by direct vassals of the empire have a tendency to appoint members of their royal house instead. Outside of direct vassals, tributary states also exist that supply Mali with periodic gold and slaves, mostly in Nigeria. The largest of these tributary states include Jabal Asada, Bononam, and Oyo.

The Saharawi Sadiyanate is also a vassal of Mali, which is populated by the descendents of Hendrickus Pisacus or "Al-Ismak" and his Franconian Islamic converts. The rulers or "Sidi" of the Sadiyanate hold a special relationship with the Mansa of Mali, through the personal connection Pisacus had with Mansa Musa. By tradition, the wife of the resident Sidi is appointed as one of the concubines from among the imperial harem of the Mansa.

Within the direct demesne of the Emperor, two types of governors that ruled local regions are called Farin or Farba. The Farba is a permenant administrative position that has the privelege of surveying and collecting taxes from a region, which is appointed and reports directly to the Mansa. This title is held with great esteem and is also passed down biologically with approval from the government. the Farin is a non-permenant office, directly controlled by the military and not allowed to collect taxes except on a case-by-case basis. The Farba office is used for recently-conquered regions before a suitable Farin is appointed, or created into a vassal.

List of Mansas[]

| Name | Reign | Born | Succession | Dynasty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musa I | 1323-1346 | 1280 | Conquest, married Fatima bint Abdullah | Keita |

| Ayyob | 1346-1368 | 1307 | Son of Musa I | Keita |

| Mustafa | 1368-1386 | 1326 | Son of Ayyob | Keita |

| Dawud I | 1386-1405 | 1335 | Son of Ayyob | Keita |

| Musa II | 1405-1423 | 1363 | Son of Dawud | Keita |

| Othman | 1423-1433 | 1381 | Grandson of Mustafa | Sefawa |

| Rabih | 1433-1458 | 1406 | Son of Othman | Sefawa |

| Dawud II | 1458-1495 | 1430 | Son of Othman | Sefawa |

| Othman II | 1495- | 1450 | Son of Dawud | Sefawa |

Economy[]

Production[]

A large portion of Mali's wealth comes from the raw materials they produce, with a smaller percentage coming from manufactured goods and trade. The main materials produced natively by Mali are salt, copper, ivory, coffee, exotic wood, and palm oil, not including the materials imported by trade abroad. Gold is also heavily produced, but is used exculsively as bullion to back the currency used by the empire when trading abroad. In terms of agriculture, Mali produces mostly sorghum and Malian rice as staple crops, along with vegetables cut from baobab plants. Other root vegetables are also common, as well as a high production of sugar.

The currency of Mali is standardized as the مثقال (Mithqal), which is set to 65.6 grains of gold. Copper and salt are also unusual forms of currency. A copper bar is set to 2 mithqals, and a camel load of salt is set to 20 mithqals, or 10 copper bars. Slaves are also a very wealthy commodity, which are captured by Mali among the vassalized pagan African kingdoms within the borders of the empire. Pagans within the empire are freely allowed to be made into slaves, in addition to a head tax of slaves taken from Mali's tributary states in Nigeria. Exports of slaves are far more lucrative in the Middle East than in Europe or the Mediterranean. Because of this, demand for slaves usually outstrip their supply and drive their cost very low. Starting in the 15th century, Spain and Portugal became a large consumer of slaves for the use of their African colonies.

Trade[]

A typical salt caravan

Mali’s greatest source of wealth comes from its trade relations. Through the Hindu-African trade union, Mali is a vital componant of the silk road that extends from Western Europe as far as China and India, affecting the trade of various East Easian and East African states along the way. The Trans-Saharan caravan trade allows Mali to have direct trade routes across the desert to either Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, or Ethiopia. Trade relations with Ethiopia tends to be the most critical, and tenuous, as they connect directly to India but is not a Muslim nation.

Through these nations, Mali trades in the same commodities they produce, in addition to the East Asian production of silk and spices that is imported. During the time of the Barbary Crusades, trade relations also existed over the caravan routes to the Kingdom of Tripolitania, which temporarily opened up new trade routes in the Mediterranean. In addition, horses are also puchased from Ethiopia, which have since been bred in local pastures in the Sahel as well.

The caravan trade has also been Mali’s greatest weakness, due to having such a large dependency on it for excess finances. During civil unrest in the succession of Sundiata and the House of Kolokan, the economy of Mali greatly suffered when the caravan trade was disrupted. One way this is combatted against is with an extensive road system, as Mansa Musa commissioned the construction of a massive road network across the entire empire in the 1330s. This road network often extends far into the desert regions as well, which are interconnected using natural oasises and supply depots.

Trade is also taken by sea across the Atlantic, allowing Mali to directly sell their goods to Portugal, Spain, Genoa, Venice, Byzantium, and the Papal States. In more recent years, Mali has established trade with "Koninklyke Bibliotheek des Lotharingen", or the Franconian West African Trading Company. In all these cases, Mali sells raw materials in exchange for more finely-manufactured goods, which is the key commodity Mali imports from the west. Spain holds the highest pre-eminence among Mali's Atlantic trade partners, due to their long-standing relations since the time of Mansa Musa, and their more recent military alliance.

In the south, Mali also trades with native African states of Nigeria and Ghana, especially the Oyo Empire. Mali holds a monopoly of trade across these regions, where there is no other state that compares to the empire's central organization and infrastructure. Mali maintains a tight tributary system in Nigeria, where tribute of gold and slaves is collected from any nations that do not convert to Islam.

Colonies[]

Renaissance depiction of the Siege of Jabal Zayiyr

Mali has a very slow, but gradually increasing, interest in becoming a leading figure in Atlantic colonization. Their primary incentive in establishing these colonies is to seek more heavy investiment in oceanic trade, in order to avoid the issue of relying solely on the Sahara Carvans. A secondary, more cultural incentive surrounds the legend of the Mansa Abu Bakr II, who first established Mali's navy and led the colonization of the Gorgades Islands. According to legend, he abdciated from power in 1312, and set sail into the ocean in order to redeem his sins, and landed in a paradisal land across the ocean.

The Malian colonization of the Gorgades islands began in 1308, which was organized by the legendary explorer Sanbao. Population of the Gorgades has been historically difficult to maintain, due to the lack of arable land and interest to stay in the region. According to legend, the islands were originally ruled by Gorgans of Greek Mythology, but archaeology indicates the islands were uninhabited before the 14th century.

Mali also has maintained colonies along the Kongo River and nearby coast of the Kongo Kingdom in southern Africa, which was named as the land of Zayiyr. These first colonies were established in the 1450s by the explorer Abu Ismail. In 1458, the Malian military leader Amir Omar Shajah organized his own expedition of 5,000 men to depose the ruler of the Kongo Kingdom, and has since been recognized by Mali as the new Mai of Zayiyr.

Military[]

Organisation[]

Military of Mali are separated between slave armies and armies of professional clans. This follows a strict hierarchy of chain of command. The Mansa himself is the commander-in-chief of all the armed forces. Two regents under him direct the armies of the north and south, called Farim-Soura and Sankar-Zouma, respectively. These are appointed by the Mansa but approved by the Gbara. Under each of these are eight Tongigi commanders, equivalent of Major Generals in Europe. The sixteen Tongigi leaders are all feudal nobles as well, and are collectively represented at the Gbara. A company of troops under each of those is called a Farari. Within each company, the officers consist of three divisions: Kelekoun for freemen, Duukunasi for slaves, and Sofa for logistics and horse breeding.

Slaves were typically used as military units

This was the extent of the military organization as first created by Sundiata, and fully organized in the reign of Mansa Musa. After the reign of Simba I, the army also adopted a hereditary structure of loyalty and training, as well as training in tactics for lancer cavalry and sieges similar to French knights. The majority of Mali's military comes from their feudal vassals, whose personal retainers and levies make up a tremendous fighting force across the empire. However, the Imperial army controlled directly by the Mansa holds the most power and prestigue, as was organized by Mansa Musa.

The total army has 50,000 active personnel, with as much as 250,000 reserve forces, but these can often vary based on the needs of the empire and the largest noble titles. Originally in 1310, the army was known to be a total size of 100,000 troops. Later on, Mansa Simba I split the army into active and reserve forces, to ensure that the active personnel was small enough to be effectively trained and equipped with the most modern means.

Mali used to import their horses from Ethiopia, but now breed their own Sahelian steeds from the descendants of these orignal imports. 10% of the army is Horon cavalry, and another 10% lancers. Of the infantry, 20% are skirmishers, 40% are Mandekalu spearmen, and 30% are archers. Additionally, there is a camel cavalry of 1,500 troops and a more elite Imperial military of 700 troops.

Equipment[]

Contemporary figurine of a Mali warrior

The backbone of Mali's army rests on their infantry and cavalry, directed under the existing military organization. Soldiers generally have chain-mail armor and wooden shields, with elite clan leaders privileged with laminar armor. The cavalry also tends to be armored on their horses. Cavalry will also have lances and crossbows, to be trained in similar manner to Roman auxiliaries.

This also varies wildly across the military, as some of the poorer skirmishers can tend to be far more lightly armored or less equipped than the regular military. The most basic equipment can be found among the vast majority of the army in some fashion, including tamba spear, knife, poison javelin, iron swords, and chain-mail. The archers will always come equipped with flaming and poison arrows. For sieges, Mali uses both elephants and catapults generally, but has also augmented using modern cannons, hand cannons, and Serpentine lever cannons.Siege warfare is not as often used by Mali, but is nonetheless a key componant of the army's training.

[]

The oceanic navy of Mali consists of a variety of ships, including galleys, carracks, and jersey cogs, amounting to a total size of 42 ships. Many of the larger ships were purchased from Mali's Atlantic trading partners, such as Spain, Portugal, and Lothringia. The Malian galleys were built based on these design, which makes up the rest of the major ships. Mali's most major portsa re located in the cities of Dakar in Waalo, and Samla in Sawhari. Koye and Nkore were other major ports used during the reign of Mansa Ayyob, but these were lost to the Qamar dynasty during the reign of Mustafa. The Sidinate, as a vassal of Mali, has been given a direct privilege of owning all the ships they construct themselves.

Since the time of Mansa Ayyob, there has been a constant contention among the Gbara between the relative support for the navy over the army. As of the time of Mansa Simba at the end of the 14th century, the navy has won out on that debate. Following the designs of the ships purchased from western Europe, Mali has mounted cannons for naval offense. In addition, anti-naval defenses with mounted cannons are placed in and around Dakar to defend from invasion. Mali also has a navy of 2,000 riverine boats along the major rivers of Senegal, Niger, and Gambia. This has been the oldest naval tradition of Mali, and existsed almost as long as the empire itself.

Religion[]

Islam is the official religion of Mali, and embraced by the vast majority of its population. Islam is also an important part of the legitimacy of the Keita dynasty, as they trace their lineage to a companion of Muhammad. Originally, Mali followed Sunni Islam for much of their hsitory. However, they started to move away from the Abbasid Caliphate after the Taymiyyah sect arose in the 1340s, as was the case for many other Muslim nations. This was compounded by the fact that Mali existed at such a remote distance from Mecca and Baghdad, such that the constant need for performing the hajj began to place a political and logistical strain on the empire. Finally, the colloquial traditions of West African Islam had already sharply diverged from the Sunni practices in the Middle East, which were only emphasized by the radical Taymiyyah sect.

In the 1350s, the Prophet Abu Yunus introduced a new sect of Islam to Mali during the reign of Mansa Ayyob, which sharply diverged from Sunni in a number of theological points. Yunus originally started as an Imam sent by the Kingdom of Waalo to preach Islam to the native people of Guinea. After spending many years in this mission, he eventaully moved to the city of Segu, form where he is sometimes referred to as "Yunus of Segu". He wrote many works of theology and poetry during this time, and afterwards began to report his prophetic visions that became the cornerstone for the Islamic reformation. He was also known to perform various miracles, which he gave as a sign of his divine message as the proper successor to the Prophet Muhammad.

Yunni Islam teaches that the Caliphate ceased to be rightly-guided after the death of Al-Mansur in the 9th century AD, and from that time until the Prophet Abu Yunus, there was an interregnum in the Caliphate. It also replaces the five pillars of Islam with the “three rings”: fasting at Ramadan, prayer four times a day, and the Shahada (or declaration of faith). Other mandates of Islam, such as Hajj (pilgrimage to mecca), Zakat (poor tax), headscarfs and blasphemy laws were optional, and should not be imposed legalistically. Instead, these traditions had been replaced with practices borrowed from West African tradition. Through this pseudo-syncretism, Yunni Islam has proved to be much more successful and popular among the regions of West Africa and Nigeria that Mali preaches in.

Manuscript copy of On Death by Idris

This reformation of religion allowed Mali to move away from the Abbasid Caliphate and center religion within the empire itself, while also accommodating African traditional culture. The Caliphate of Mali, starting with Abu Yunus’ disciple Idris Al-Segu, administrates the religion as the direct successors of the Prophet in that same city. In general, Yunni Islam has been the most successful within the Mali Empire, while Sunni Islam persists across the Empire of Bornu and parts of the Sahel. This religious divide became a key issue during the conflict of the Sefawe War.

Pagan African religions also exist in the empire, which are heavily suppressed from public life and often persecuted. African pagans are offered to convert to Islam for a number of benefits, including higher ranks in government, lower taxes and better education, as well as exemption from being forced into slavery.

Humanism is the main philosophy espoused by Malian theologians, and adopted in state policy as well. This comes mainly from European influence, and largely found among the writings kept in the Library of Timbuktu and the Library of Dakar. On of the most pivotal works of philosophy was the theologic text On Death, attributed to the first Manding Caliph Idris Al-Segu.

Culture[]

Demographics[]

The total population of the Mali Empire is 24 million people. It originally started as 3 million in 1250, and grew to 10 million at the conquests of Musa in 1320. The core of Mali’s empire is Mande, an ethnic group of the Nilo-Saharan family. However, the empire is extremely diverse and has many ethnicities that originate from the Niger-Congo family, as well as Berbers and other Semetic groups in the northern desert regions. Because of this diversity, most people in the empire are multilingual and can understand at least 2-3 languages. Due to the general affinity to Islam, Arabic is the most common script to use in all written documents. Other scripts are phonetic translations of Mande and Tameshq (Berber) using the Arabic alphabet.

In terms of class, the majority of Mali’s massive population end up being on lower income in general, with much emphasis placed on peasant populations. An upper middle class is slowly growing in the most major trade cities like Dakar and Timbuktu, with a minority of the population in nobility. A rather large portion of the population are either slaves or tribal societies.

The Semetic people of North Africa are a major ethnic group to this day

Pagan African minority groups are treated with much disdain, and end up being heavily suppressed. Forceful assimilation to Manding culture is commonplace, which is a large source of Mali’s slavery. In the past, secret societies were used to help enforce this assimilation, which was started in the time of Musa but was discontinued by Simba. Berbers and other Semetic people in the north, however, are often less integrated. The Sahwari Sidinate, however, is exempted and are allowed to retain their Franconian language, because they are descended of Lotharingian immigrants that came at the time of Hendrickus Pisacus.

Education[]

Mali has a nation-wide, mass education system that provides accessibility of vital knowledge to everyone in the nation. However, it is not public and is charged with an additional tax. As a result, it has become largely used by the wealthy and draws a sharp divide between urban and tribal societies. Education is also used as a form of state-wide assimilation, as it indoctrinates the population to accept either Mande or Berber culture. As a result, many local tribal populations opt out of the education intentionally in order to retain their traditional way of life.

This education system was completed by the time of Simba I, and since that time the younger generation of Mali has gradually experienced westernization. Universities are the highest form of education in Mali, where the largest are the University of Timbuktu and the University of Dakar. The Library of Timbuktu, having over 700,000 books, has collected knowledge from across Europe and the Middle East, and carefully translated all this knowledge into phonetic scripts of Tameshq and Mande. The scholarly works of Timbuktu have expounded on topics of mathematics, biology, history, medicine, philosophy, and art. Collectively, this cultural movement of advancement in the Sahel has been known as the “African Renaissance”.

Ibn Ishaq is the most famous mathematician of the 1360s, who wrote works on mathematics about music and Euclidean geometry. His works were very foundational to later innovations on architecture. Furthermore, Ishaq's theory on mathematics and philosophy was revolutionary in being able to break down all of science and mathematics to a set of Euclidean postulates or "first principles", which later formed the basis of Mali's entire education system.

Art and Architecture[]

Originally, the most significant aspect of Mali's architecture was the style unique to Sub-Saharan Africa known as Sudano-Sahelian architecture. Dating back to the late iron age, this architecture was characterized by mud bricks and adobe plaster, studded together with long wooden beans that jetted out in a very distinctive pattern. The most predominant form of this architecture was the Malian style, but other regional styles existed as well: the Fortress style most common in Timbuktu, the Tubali style found in Hausa and Agadez, and the Volta style found in the southern territories around Burkina Faso.

The most pivotal example of this style was the Great Mosque of Djenne, one of the few historic buildings still preserved since the reign of Mansa Abu Bakr II. Later on, the Larabanga Mosque was constructed in the 1420s by the Qamar Dynasty in Bononam, which was the last monumental work attributed to this old style.

Mali officially branched off from the Sudano-Sahelian style as a result of the reforms of Masna Ayyob in the 1350s. Since that time, Mali's architecture is heavily focused on intricate domes and arches, similar in style to the Mosque and palace of medieval Cordoba. This is enhanced with the use of spired minerets, clealry influenced from Gothic style of Mali's trading partners in Europe. This also is used with various stained glass and glass chandliers across the domes, which have collectively been described as the "Sahelian Gothic".

Additionally, the reforms of Mansa Ayyob permitted art to depict religious events as well, both humans and animals, which was accepted by the recently-reformed Yunni Islam while forbidden in Sunni. Thus, the most vivid and colorful depictions of both the Quran and Muhammad's life can be found within the Grand Mosques in Timbuktu and Dakar. The Nabi Yunus Mosque in Timbuktu is the single largest religious building in West Africa, and incorporates the best examples for this style of art.

This modernized architecture has extended far beyond religious works as well, and in general the cities of Timbuktu and Dakar take on a very Renaissance look compared to most other cities in Sub-Saharan Africa. The road system extended across the Empire by Mansa Musa, in conjunction with modern architectual styles and the academic architecture at the University of Timbuktu have solidifed the city to have as much of a modern feel as parts of Western Europe, or reminsicent of medieval Al-Andalus. This is drastically contrasted by more rural or suburban villages in the center of the Empire, however, where poverty or even tribalism is much more prevelant.

The best example for secular Sahelian Gothic art is found in the Palace of Musa, constructed in the Malian capital of Niani late in Musa's reign. The courtyard of the palace of Niani is built indoors, with fifty marble columns on either side of the building, and a glass domed roof over it. Inside the court yard is an elaborate garden filled with trees, grapevines and many other plants. The marble columns are also adorned with images of plants and flowers, and paintings of birds and lizards as well. Around the outside of the palace includes various smaller wings for servants, concubines, family quarters and guest rooms. There are three separate throne rooms to the palace as well: one to hold public court and entertain guests of both peasants and foreign rulers, one to hold private court with his nobles and ministers and discuss matters of state, and one for purely ceremonial purposes with religion.

Literature[]

The core of Mali's literary tradition is their national epics, which are literary cycles that center on the hagiography of a single heroic individual. The earliest and most famous national epic is the Epic of Sundiata, which details the foundation and early growth of the Mali Empire under Sundiata Keita. These epics were originally an oral tradition, but Mansa Ayyob began to popularize the use of writing in the 1350s. However, it wasn't until the reign of Musa II in the early 15th century that the former oral tradition really gave way to popular literature. It was also during the reign of Ayyob that the use of poetry in the Tamashq language became popularized. Particularly in the Library of Timbuktu, non fiction works are also very prominent as commentaries on classical Greek and Arabic texts. Starting with the body of revelations published by the Prophet Abu Yunus, religious works of literature and religious philospohy also have been important contributions to Malian culture. List of notable works of literature:

- National epics:

- Epic of Sundiata Keita

- Epic of Mansa Musa

- Voyages of Sanbao

- Epic of Mansa Simba

- Manding Book of Kings (collection of all four)

- Religious works:

- Poetic works of Abu Yunus

- Revelations of Abu Yunus

- Hagiagrophy of Abu Yunus

- On Death by Idris Al-Segu

- Poetry:

- The Wonderful Life (Tameshq translation of original French)

- The Opal Beauty of Africa

- Non Fiction:

- Commentary on A Geometry of a Sphere by Ibn Ishaq

- Itinerary of Hendrickus Pisacus

- Itinerary of Ibn Battuta

- The Introduction by Ibn Khaldun

| Archives List | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century | 14th century | 15th century | 16th century | 17th century | 18th century | 19th century | 20th century | |

|

1300-1309 |

1400-1409 |

1500-1509 |

1600-1609 |

1700-1709 |

1800-1809 |

1900-1909 | ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|}