The Italian Republic (it: Repubblica Italiana) or simply Italy (it: Italia) is a state in Southern Europe located in the very center of the Mediterranean. Formed following a nationwide referendum on 2 June 1946, which abolished the monarchy and introduced a republican form of government.

The largest cities are Rome, Milan, Naples, Turin, Genoa, Palermo.

State structure[]

The state structure of Italy is determined by its constitution, adopted on 22 December 1947. According to its provisions, Italy is a unitary democratic republic of parliamentary type.

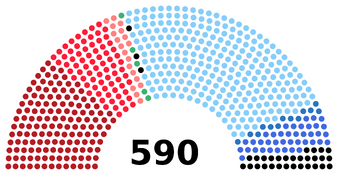

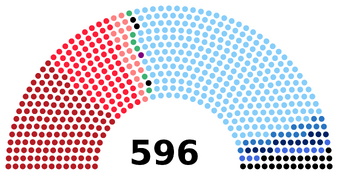

Legislative power is vested in a bicameral parliament. The lower chamber is the Chamber of Deputies (it: Camera dei Deputati), elected by the population on a proportional basis. The country's territory is divided into 31 districts (it: Circoscrizioni) of unequal size, each of which elects a fixed number of deputies. To get into parliament, a party needs a minimum of 300,000 votes at the national level and 60,000 votes in at least one of the constituencies. The votes cast for the parties that did not receive seats in any of the constituencies are summed up in the "32nd district", which also sends a certain number of deputies to parliament.

The Senate (it: Senato della Repubblica) — the upper house of parliament — is also elected by the population on a regional basis. Each region is divided into single-mandate constituencies — to be elected, a candidate needs to get 65% of the vote, which almost never happens. From the constituencies in which no one was elected, a single regional constituency is formed, the seats in which are distributed in proportion to the votes cast.

The head of state is the President (it: Presidente della Repubblica Italiana), elected at a joint meeting of both houses of parliament with the participation of representatives of the provinces for a 7-year term. The elections are held in several rounds — if in the first three rounds none of the candidates received 2/3 of the votes, then in the fourth and subsequent rounds the president is elected by a simple majority. To be elected, a presidential candidate must be at least 50 years old and have all civil and political rights. The re-election of the president is allowed, as well as the extension of his powers if both chambers are dissolved and cannot elect a new head of state.

Meeting of the Italian Chamber of Deputies

In the Italian political system, the president has mainly representative functions. The real power is concentrated in the government — the Council of Ministers (it: Consiglio dei ministri), headed by the President of Consil Minister or Prime Minister (it: Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri). Formally, he is appointed by the president, but in fact he is the representative of the parliamentary majority.

The highest court is the Supreme Court of Cassation (it: Corte suprema di cassazione). The judicial body of constitutional control is the Constitutional Court (it: Corte costituzionale). Geographically, Italy is divided into 20 regions (it: Regioni), 5 of which —Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Valle d'Aosta and Friuli-Venezia Giulia — have a special status. Regions are divided into 110 provinces (it: Provincia), and those into 8101 communes (it: Comune).

List of Italian Prime Ministers[]

| № | Photo | Name | Term | Coalition | President | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Alcide De Gasperi

(1881—1954) |

13 July 1946[1] | 2 February 1947 | National Liberation Committee

(DC • PCI • PSI • PRI) |

Enrico De Nicola

(1946—1948) | ||

| 2 February 1947 | 31 May 1947 | National Liberation Committee

(DC •PCI • PSI • PDL) | ||||||

| 31 May 1947 | 23 May 1948 | Centrism

(DC • PSDI • PL •PRI) | ||||||

| Luigi Einaudi

(1948—1955) | ||||||||

| 23 May 1948 | 27 January 1950 | |||||||

| 27 January 1950 | 26 July 1951 | Centrism

(DC • PSDI • PRI) | ||||||

| 26 July 1951 | 16 July 1953 | Centrism

(DC • PRI) | ||||||

| 16 July 1953 | 17 August 1953 | DC | ||||||

| 2 |

|

Giuseppe Pella

(1902—1981) |

17 August 1953 | 18 January 1954 | ||||

| 3 |

|

Amintore Fanfani

(1908—1999) |

18 January 1954 | 10 February 1954 | ||||

| 4 |

|

Маrio Scelba (1901—1991) |

10 February 1954 | 6 July 1955 | Centrism (CD • PSDI • PLI) | |||

| Giovanni Gronchi

(1955—1962) | ||||||||

| 6 July 1955 | 7 July 1957 | |||||||

| 7 July 1957 | 1 July 1958 | CD | ||||||

| 5 |

|

Antonio Segni (1891—1972) |

1 July 1958 | 16 February 1959 | Centrism (CD • PSDI • PLI) | |||

| 16 February 1959 | 25 Mars 1960 | CD | ||||||

| 6 |

|

Fernando Tambroni (1901—1963) |

25 Mars 1960 | 5 November 1960 | ||||

| (3) |

|

Amintore Fanfani (1908—1999) |

5 November 1960 | 8 Mars 1961 | ||||

| 7 |

|

Giovanni Leone (1908—2001) |

8 Mars 1961 | 21 February 1962 | Right-Centrism (CD • PLI) | |||

| 21 February 1962 | 21 June 1963 | |||||||

| Antonio Segni

(1962—1969) | ||||||||

| 8 |

|

Giulio Andreotti (1919—2013) |

21 June 1963 | 25 June 1964 | ||||

| 9 |

|

Cesare Merzagora (1898—1991) |

25 June 1964 | 11 February 1965 | Right-Centrism (CD • PLI • PRI) | |||

| 11 February 1965 | 13 June 1967 | |||||||

| 10 |

|

Mariano Rumor (1915—1990) |

13 June 1967 | 24 June 1968 | ||||

| (7) |

|

Giovanni Leone (1908—2001) |

24 June 1968 | 12 December 1968 | CD | |||

| (8) |

|

Giulio Andreotti (1919—2013) |

12 December 1968 | 22 October 1970 | Right-Centrism (CD • PLI • РRI) | |||

| Giovanni Leone

(1969—1976) | ||||||||

| 22 October 1970 | 10 April 1971 | CD | ||||||

| 10 April 1971 | 13 July 1972 | Right-Centrism

(CD • PLI • PRI) | ||||||

| 11 |

|

Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (1918—2012) |

13 July 1972 | 26 July 1973 | Cuadripartito (CD • PLI • PRI • MSI) | |||

| (10) |

|

Mariano Rumor (1915—1990) |

26 June 1973 | 5 November 1973 | CD | |||

| 12 |

|

Emilio Colombo (1920—2013) |

5 November 1973 | 19 May 1975 | Cuadripartito (CD • PLI • PRI • MSI) | |||

| (8) |

|

Giulio Andreotti (1919—2013) |

19 May 1975 | 20 June 1976 | ||||

| Guido Gonella

(1976—1982) | ||||||||

| 13 |

|

Arnaldo Forlani (b. 1925) |

20 June 1976 | 28 February 1977 | CD | |||

| (11) |

|

Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (1918—2012) |

28 February 1977 | Cuadripartito (CD • PLI • PRI • MSI) | ||||

List of parliaments of Italy[]

History[]

On the eve of the 1953 elections, Alcide De Gasperi, who had headed the government for more than 7 years, tried to achieve changes in the electoral legislation that would allow the party, which received more than half of the votes, to count on 2/3 of the seats in parliament. However, on voting day, 7 June, only 49.8% of voters voted for the Christian Democrats and their allies in the centrist coalition (democratics socialists, liberals, republicans, as well as Sardinian and Tyrolean autonomists) — despite the fact that the coalition had majority in parliament, the number of votes cast for the CD decreased by almost 2 million.

On 2 August, the Chamber of Deputies passed a vote of no confidence in the Gasperi government, and two weeks later he resigned as prime minister. Italy entered a period of political instability and frequent changes of government, which lasted more than a quarter of a century.

Giuseppe Pella's cabinet[]

Trieste residents celebrate the annexation of Italy

After de Gasperi's resignation, Italian President Luigi Einaudi appointed Giuseppe Pella, a former minister of state property known for his liberal monetarist policies and dislike of left-wing parties, to head the government. It was emphasized that the Pella government would be temporary, created only to develop a new budget, but even in such a short period of time, Pella managed to provoke an acute diplomatic crisis with Yugoslavia, deploying Italian troops on the Italian-Yugoslav border in August—September and receiving guarantees from the United States and Great Britain on 8 October about the transfer of the territory of Trieste to Italy, which caused the real fury of Josip Broz Tito. On 3—6 November, an uprising even broke out in Trieste, the participants of which demanded immediate annexation to Italy — a war could break out between the two countries of Southern Europe at any moment. Pella's actions were heavily criticized by the Italian communists and socialists, but found support from the monarchists and neo-fascists of the Italian Social Movement (MSI). On 12 January 1954, Pella resigned.

Mario Scelba's cabinet[]

After Pella's resignation, the government was headed for 24 days by Amyntore Fanfani, who never managed to get the Chamber approval. The only measure that Fanfani managed to carry out was the strengthening of measures to combat communist subversion, the implementation of which was entrusted to 35-year-old Interior Minister Giulio Andreotti.

Mario Scelba at a rally

On 10 February, Mario Scelba became the new prime minister. He managed to resolve the issue of Trieste peacefully — on 5 October, an agreement was signed in London, according to which the disputed territory was divided approximately equally between Yugoslavia and Italy, but the city itself ceded to the Italians. In addition, on 31 July, the electoral law granting two-thirds of the seats in parliament was canceled to the party that received the majority of the votes, which received the title of the "Fraud Law" from the opposition.

Nevertheless, despite these measures, the Scelba government and its chairman personally were constantly criticized — on 9 February, Gaspare Pisciotta was found dead in prison — one of the perpetrators of the massacre of Italian communists in Portella della Ginestra in 1947, suspected of organizing which fell including on Scelba. The PCI press, immediately after Pisciotta's death, tried to accuse the newly appointed prime minister of covering up his tracks, although no evidence could be found. Another major scandal was the death of model Vilma Montesi, in which the son of the foreign minister was involved.

In an effort to enlist the support of the United States, Scelba at the end of 1954 intensified the persecution of the communists, which ultimately only played into the hands of the PCI, allowing it to assert itself as a real defender of political freedoms and constitutional rights. On 15 December 1955, the Constitutional Court was finally established. On 25 March 1957, an agreement was concluded between Italy, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg on the creation of the European Economic Community — the parties agreed on a single agricultural policy, free movement of capital, labor and services, uniform customs tariffs, etc. Scelba's government lost support of democratic socialists and liberals in May 1957, having lost the majority in parliament. The new president, Giovanni Gronchi, instructed Schelbe to form a one-party Democrat-Christian cabinet. On 7 June, during the voting in the Chamber of Deputies, monarchists and neo-fascists voted for his candidacy, which became the reason for new accusations against Scelba from the left flank.

Economic miracle[]

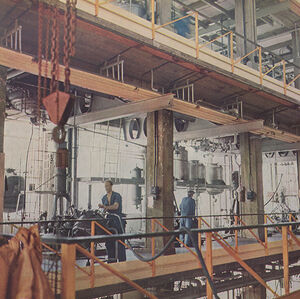

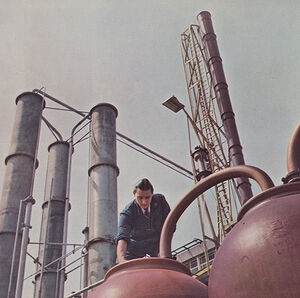

Bracco chemical plant in Milan

The Mario Scelba's reign was the dawn of the Italian economic miracle, made possible by US aid under the Marshall Plan, which was purposefully provided by the largest corporations such as Fiat, the Korean War, which caused the need for steel for the production of tanks and aircraft, and the discovery of deposits in the Padua Plain methane and hydrocarbonates, which spurred the development of ferrous metallurgy. The growth rates of the Italian economy during this period were ahead of all other states of Western Europe, and on a global scale they were second only to Japan. The growth was particularly impressive in the automotive, electronics and chemical industries.

State levers were actively used to re-equip industry — the State Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (IRI), created under fascism, remained and continued to play an important role in long-term lending to industry. With the discovery of oil reserves in Italy in 1957, the state-owned company "Eni" (National Liquid Fuel Administration) was established, completely taking over a new industry — the petrochemical industry. State capital investments in 1952—1953 amounted to 41% of all investments, and in 1959 only the Institute of Industrial Reconstruction and "Eni" accounted for 30% of their total mass.

The intensive development of industry caused a massive migration of the rural population to the cities, especially from the southern regions. The agrarian reform carried out by the Gasperi government did not lead to the creation of any significant layer of viable peasant farms, as a result of which individual plots were mostly small and medium-sized, unable to compete with large agricultural enterprises. Many peasants who received land abandoned their allotments. With a huge pool of workers, Italian entrepreneurs were able to keep industrial wages at a lower level than in other EEC countries, and thereby reduce production costs and increase the competitiveness of their goods.

A sharp increase in the industrial potential of the North occurred while the agrarian South continued to lag behind. A total of 1.8 million people left the village during the 1950s and 1960s, but this led to the phenomenon of "false urbanization" — the cities were overgrown with slum suburbs with many empty apartments in the cities themselves sold at unaffordable prices.

Antonio Segni's cabinet[]

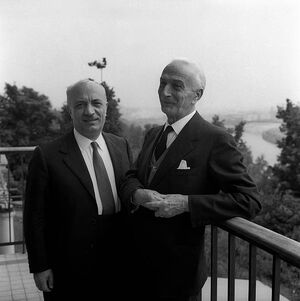

Amintore Fanfani and Antonio Segni — leaders of the left and right wings of CD

At the regular parliamentary elections held on 25 May 1958, the bloc of communists and socialists received almost 1.5 million votes more than five years earlier, but support for the CD also increased by about the same amount — as a result, a three-party government was formed from Christian Democrats, Liberals and Democratic Socialists, headed by 67-year-old Antonio Segni, who was former minister of agriculture and education in de Gasperi's cabinet.

Segni was the leader of the right-wing in the party, which by the late 1950s had gained the upper hand over the supporters of Amintore Fanfani, who advocated inclusion in the ruling socialist coalition. The failure of negotiations with the leader of the Socialist Party Pietro Nenni, who remained faithful to the pact of unity of action with the Communists, predetermined Fanfani's defeat in the internal party struggle and of the displacement of the CD "to the right." Despite the fact that the conservative dominated the Segni's cabinet, he carried out a number of social reforms — for example, agricultural workers were provided with sickness insurance, civil servants' pensions were increased, and a monthly allowance was introduced tied to the standard of living of the population.

Fernando Tambroni's cabinet[]

Armed clashes at Piazza Ferrari in Genoa

On 25 March 1960, Antonio Segni resigned from the post of head of government and his closest associate Fernando Tambroni became the new prime minister. The new cabinet, which consisted only of Democratic Christians, had only two tasks — to hold the Summer Olympic Games in Rome at the proper level and to adopt a budget by the end of October, after which it could be dissolved. However, the political crisis arose two weeks after Segni's resignation — on 8 April, the Chamber of Deputies support the Tambroni government by a majority of only 3 votes, consequently the neo-fascists and monarchists actively voted for it. After that, three ministers immediately resigned from their posts in protest, forcing Tambroni to do the same on 11 April, but President Giovanni Gronchi refused to accept the resignation of the entire cabinet and on 29 April — again with the support of the neo-fascist MSI — the Tambroni cabinet received the majority of votes and Senate.

The leader of the MSI at that time was Arturo Michelini, who was trying with all his might to turn the party from fascist to conservative — in the Tambroni government, he saw a chance for the MSI to get out of political isolation and become a full-fledged force in parliament, which could participate in determining the state course. On 14 May 1960, the MSI decided to hold the 6th Party Congress in Genoa, a city known for its close ties with the Resistance Movement during the years of fascism, which provoked an outburst of indignation on the left. From 15 June to 19 July in Genoa, demonstrations were regularly organized by communists, socialists, demosocialists, republicans and radicals demanding the abolition of the congress, in which up to 30,000 people participated, but Tambroni and Michelini refused to make concessions — only thanks to the efforts of Prefect Luigi Pianese managed to reach a compromise, according to which the congress of the MSI was nevertheless held in Genoa, but not in the Teatro Margherita, as previously assumed, but in the Ambra di Nervi theater, in order to exclude the possibility of meeting participants of the congress with a demonstration of anti-fascists that took place on the same day.

However, despite all the security measures, on the day of the opening of the congress on 2 July, bloody clashes between opponents of the congress and the police took place in Genoa — 9 people died, the exact number of victims could not be established: the police announced 36 wounded, the opposition — about 500. On 14 July, Tambroni directly accused the Communists of provoking the violence, linking its outburst with Togliatti's visit to Moscow on 21 June. During the days of the congress, anti-fascist demonstrations were also held in Rome, Turin, Milan, Livorno, Ferrara, Palermo and other cities.

Opening ceremony of the XVIIth Summer Olympic Games in Rome

Despite the fact that virtually all parties to the left of the CD went into opposition to the government, Tambroni successfully held the Olympics, in which the USSR won for the second time in a row, and achieved the adoption of the state budget thanks to the votes of the MSI and the monarchist party. Fulfilling his obligations, on 5 November, he resigned — the government was again offered to be lead by Fanfani, but he once again failed to agree with the socialists on the formation of a coalition and on 8 March 1961, the right wing of the Christians Democrats openly opposed the new prime minister who also left his post.

Giovanni Leone's cabinet[]

At the suggestion of President Gronchi, the government was headed by the chairman of the Chamber of Deputies, Giovanni Leone — he did not belong to either the right or the left wing of the CD and therefore, it was believed, could create a viable coalition of moderate parties. However, by that time, two traditional allies of the CD — demosocialists and republicans — had already gone over to the opposition camp: the leader of the Republican party, Hugo La Malfa, refused any coalition negotiations at all, and the head of the PSDI Saragat agreed to support Leone only if he broke every connections with monarchists and MSI.

Leone tried to create a three-party government, including representatives of the Saragata party and the liberals, but at a meeting with the new leader of the PLI, the banker Giovanni Malagodi, unexpectedly received his consent to be included in the MSI coalition. Malagodi headed the far-right faction in the PLI — under him the party actually switched to conservative positions and, most importantly, he did not want to hear not only about negotiations with the socialists, but also about the inclusion of very moderate supporters of Saragata and La Malfa in the coalition, considering them too left. As a result, the Leone government became bipartisan — it included several members of the PLI, including Malagodi, who became deputy prime minister, and in parliament, support for the government was also provided by the monarchists and the MSI. The created coalition was notable for sufficient stability, controlling almost 3/5 of all seats in parliament, in connection with which among political scientists the period in the history of Italy, which began in 1960 or 1961, is usually called the era of "Center-Right" (in italian — "Centro-Desta"), in counterbalance to the previous decade as the time of "Centrism" in politics.

Giovanni Malagodi — leader of the Italian Liberal Party

Arturo Michelini — leader of the Italian Social Movement

The formation of a "center-right" coalition caused an ambiguous reaction in the world — British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and French leader Charles de Gaulle expressed their concerns about the alliance of the CD with the once neo-fascist MSI. At the meeting of Leone with the new US President Kennedy on 13 June 1961, it was also not possible to get unequivocally approval of the course chosen by the Christians Democrats — Kennedy had just returned from Vienna, where he held talks with Soviet Prime Minister Malenkov, and still cherished hopes of normalizing relations with the Eastern Bloc, therefore he would be much more comfortable if the Italian government was headed by Amyntore Fanfani representing the left-wing of CD. Leone received unconditional support only from Spain, Portugal and Greece, where right-wing authoritarian regimes remained.

On 2 May 1962, the government strengthened its position by securing the election of Antonio Segni, the leader of the right-wing of the CD, as president. This, as well as the continuing "economic miracle", one of the manifestations of which was the doubling of Italian GDP in 1962 relative to the 1950 level, allowed the Leone government to work without major political crises for more than two years — quite a long time by Italian standards.

Giulio Andreotti's first cabinet[]

In the elections on 28 April 1963, the left-wing parties improved their result by almost 1.7 million votes and their share in the Chamber of Deputies increased to 46.1%, while the CD's rating collapsed due to events in Genoa and it lost 23 seats. Unexpectedly, the fourth place was taken by the liberals — for the right, who were afraid to vote for monarchists or neo-fascists, Malagoda's party turned out to be the most acceptable. Shortly before the elections — in February — a draft constitutional reform proposed by the Democratic Christians, which provided for the introduction of a fixed number of deputies in parliament, failed, which is why Premier Leone announced that he would not seek an extension of his powers after the elections. Then the post of head of the Council of Ministers was offered to Defense Minister Andreotti, who became famous as the organizer of the Olympic Games.

Andreotti was a man of far-right views — a deeply religious Catholic, he most consistently opposed any cooperation of the CD with the communists, often resorted to the services of special services to collect dirt on his political rivals, and, as it turned out later, was closely associated with the mafia. Nevertheless, due to his caution and attentive attitude to his own image, he enjoyed some support.

US President Kennedy accompanied by Prime Minister Andreotti during a visit to Rome

The new cabinet, like the Leone government, consisted of Christian Democrats and liberals, and in parliament also relied on the support of the monarchists and the MSI. However, due to the fact that the representation of the right-wingers decreased, they had to forget about the previous stability — the opposition was provoked by proposals for a reform of the parliament, a new stage of European integration and an increase in the powers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Many Christians Democrats, led by Fanfani and Moro, also opposed the head of government, the latter of whom retained the post of national secretary of the CD.

To gain control of the party, Andreotti had to somehow get rid of Fanfani and Moro. For this, on the instructions of the Prime Minister in 1963—1964, a secret group headed by Colonel Renzo Rocca was created, which was involved in organizing provocations during rallies and demonstrations of the left in order to discredit them. Through the efforts of provocateurs and the press loyal to the conservatives, Andreotti achieved a change in the leadership of the Republican Party — the “leftist” La Malfa was replaced by the “rightist” Randolfo Pacciardi, who took a course to support the ruling coalition. In January 1964, Moro was forced to resign from his post as National Secretary of the CD, which, as a result of intraparty elections, went to the much more conservative Arnaldo Forlani.

The main internal political events during Andreotti's first tenure as prime minister were the terrorist attack in Villabat on 30 June 1963, which occurred during the "mafia war" in Sicily and caused a wide resonance in society, as well as the disaster at the Vajont Dam on 9 October of the same year, which the communist press used to discredit the authorities and the "Electric Society of the Adriatic", who tried to hide the true causes of the accident (one Christian Democrat newspaper even declared it to be the only cause of "God's will"). Both events negatively affected the image of the Christian Democrats, but at the same time formed a demand in society for a “strong hand” and strengthening of administrative control.

Cesare Merzagora's cabinet[]

Cesare Merzagora

The Republicans expressed a desire to re-enter the government, but the figure of the Conservative Andreotti as prime minister did not completely satisfy them, therefore, after consulting with President Segni, he resigned on 25 June 1964, and the "technocrat" Cesare Merzagora, who was the head of the Senate, became the new chairman of the Council of Ministers. The government included representatives of the CD, PRI and PLI, and in parliament, support for them was again provided by the far-right and autonomists.

Merzagora tried to implement constitutional changes, but the resistance of the three left parties buried his proposed amendments to the basic law. Nevertheless, during the years of his premiership, a number of important decisions were made — from 18 December, medical insurance was included in the number of compulsory social benefits for pensioners, from 17 October 1965, a law on the indexation of population income came into force, and at the suggestion of Malagoda and the Minister of Justice, Guido Gonella in the same year, a commission was established to review the terms of the Concordat between Italy and the Vatican. Merzagora, being the leader of the Christian Democrats, was ironically an atheist, and therefore supported the idea of a new Concordat, which, however, provoked opposition from traditional Catholics, including Andreotti, who went over to the enemie camp of the new prime minister. Added fuel to the fire was the fact that in addition to Malagoda and Gonella, the socialist Lelio Basso entered the commission, which already alarmed all Italian conservatives and almost led to the government losing support from the monarchists and the MSI. As a result, the idea of a new concordat was safely buried.

"Hot Autumn"[]

In May 1965, an acute political crisis broke out in France, which grew into a general political strike, in which about 11 million people participated at its peak — on 30 May, at the request of President Mitterrand, NATO troops entered French territory in order to prevent the communist revolution. Although the Italians did not directly participate in the invasion, the government of Merzagora came out not only with its full approval, but, in fact, became the key initiator of the force option. The prime minister criticized the policy of the French leadership back in December 1964, and later, through the NATO Secretary General, Italian Manlio Brosio, indirectly participated in the development of Operation Loire and the measures that preceded it.

Luigi Longo speaking

Merzagora's actions sparked an outcry on the part of the Italian left, which eventually resulted in "Hot Autumn": unlike France or Yugoslavia, where political protest grew rapidly and just as quickly faded away, in Italy it was preceded by lengthy preparation. The new leader of the PCI Luigi Longo, who replaced Togliatti, who died on 21 August 1964, called on the workers to go on strike in support of the French comrades, but in June—November 1965, the communists were mainly engaged in propaganda work in enterprises — during the economic boom, the literacy level of Italian proletarians, because of which they were actively involved in the political struggle, often acting together with students, many of whom were from workers and peasant families. The main requirements put forward by the left were the introduction of factory self-government, an increase in wages, a limitation of the working week to 40 hours, the conclusion of collective labor agreements, improvement of working conditions, etc.

At the end of November, the center of the confrontation was the city of Avola in Sicily — on 2 December, police shot a demonstration of agricultural workers, killing two and wounding another 48 people, including a three-year-old girl. These events, which went down in history as the "Avola massacre", became the trigger for a nationwide protest: in January 1966, the workers were supported by students of the University of Trent, who seized the building of the sociological faculty and demanded educational reforms; on 8—9 April , barricade battles unfolded in Battipaglia, nearby from Salerno, during which about a hundred people were wounded by bullets, and two — a young teacher and a 12-year-old newspaper boy — were killed. By autumn, the protests reached a peak, their center shifted from the south of the country to the north. The main arena of workers' struggle was Turin, where the factories of the Fiat company were located: on 29 October, the day of the opening of the car dealership, the strikers seized the building of the Fiat Mirafiori factory, destroying several workshops in it. Only the intervention of the Minister of Labor forced the leadership of the campaign to make concessions.

On 3—4 November, the strongest flood in the modern history of Italy occurred in Florence, during which 5,000 families were left homeless, the city's infrastructure was destroyed, about 14,000 works of art and 3 million books and manuscripts from the collection of the National Central Library were damaged. At that time, this tragedy stopped the political protest, and students from all over the country, who yesterday participated in the seizure of universities, took part in the rebuilding of the city as volunteers. At the same time, it was in Florence that the Italian students realized their unity and later acted as an organized force.

Protester with a Stalin's portrait

On 21 December, with the mediation of the government, negotiations were held between trade unions and business owners, at which the latter agreed to make concessions: to increase wages, pensions for workers, reduce working hours, etc. After that, the proletariat stopped actively participating in the protests, but the student movement continued to gain turnover — in Rome, Milan, Turin, Naples, Pisa and Trent, the work of universities was paralyzed, even part of the Catholic clergy, under the influence of Latin American "liberation theology", supported the leftist slogans and began to call for reforming the state and the church. The events in the capital culminated in the protests: at the beginning of 1967, the government announced a draft education reform that would tighten discipline, in response to which the Sapienza University building was seized on 2 February. On 29 February, the police began a sweep of the university, several thousand students fought with it and, quite unexpectedly, were able to force the police to retreat. However, almost immediately, riots broke out between the students themselves, among whom there were many neo-fascists from the University Front of National Action (the youth wing of the MSI), as well as those who broke away from the MSI because of disagreement with the moderate course of Michelini, the "National Avant-Garde" and the" Center for Research of the New Order "— in the current conditions, the leaders of the neo-fascists called on their supporters to support the government's actions and break all ties with the instigators of the riots. The leadership of the PCI also tried to dissociate itself from the students, among whom there were many Trotskyists, who were directly hostile to the Italian Communist Party, but they nevertheless condemned the actions of the police. On 16 March, control of the university had passed into the hands of the government. In total, 626 people were injured in the riots, 272 were arrested.

Gradually, the wave of student demonstrations began to decline — in the autumn of 1967, they could still gather tens of thousands of protesters, but there were no more clashes of the same scale. Nevertheless, in Italy, unlike other countries, the protest did not completely disappear and to one degree or another made itself felt throughout the 1960s and 1970s, sometimes acquiring rather violent forms.

Mariano Rumor's cabinet[]

Neo-fascist leaders Giovanni Roberti (left) and Arturo Michelini (center) with monarchist leader Alfredo Covelli (right)

The struggle around the University of Rome led to a cooling of relations within the ruling coalition — on 11 February, a congress of the monarchist party was held, to which, at the initiative of its leader Alfredo Covelli, Michelini and Malagoda were invited, having concluded an agreement between themselves to create a "democratic and national" coalition on the eve of the next parliamentary elections, which received the unofficial name "Great Right" (it: Grande destra). By that time, Merzagora did not suit both the right and the left, so on 13 June he resigned and Mariano Rumor was appointed to his place. Rumor was considered a representative of the left wing of the CD, and therefore could not count on the support of the MSI and the monarchists. An attempt to negotiate the inclusion of the demosocialists in the government also did not bring success due to the resistance of Pacciardi and Malagoda. As a result, Rumor had to form a minority government, relying only on the support of Republicans and liberals: the task before such a government was only one — to bring the country to elections, during which a new balance of power would be established.

The consequences of the protest movement of 1965—1967 were also felt among the opposition: within the PCI there was a struggle between the "right" and the "left", led by Giorgio Amendola and Pietro Ingrao, respectively. The former advocated, in fact, a gradual transfer of the party to a socialist platform, a rejection of the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism and, in the future, the inclusion of the Communist Party in a coalition with the CD. The latter, on the contrary, considered any agreement with the Christians Democrats impossible after their alliance with the ultra-right, and therefore relied on the struggle for a homogeneous left government from the PCI and PSI, for which they wanted to win over the “new left” by including many items from their programs related to feminism, environmental protection, etc. In addition, Ingrao proposed a radical revision of the party's policy in relation to religion in order to win over to his side the mass of Catholics who are dissatisfied with the “shift” of the CD to the right and, thereby, deprive it of the main part electorate.

Enrico Berlinguer and Pietro Ingrao

In addition to these mainstreams, there were also smaller groups within the party, in particular the "center" led by Enrico Berlinguer and the pro-Soviet faction of Armando Cossuta, who opposed any deviation from the Soviet version of communism. In conditions when the CD was clearly not inclined to cooperate with the communists, the left, supported by Cossuta, as well as the non-party communist group that formed around the magazine Manifesto, founded in 1969, won a majority at the 12th Congress, having achieved victory over Amendola and his supporters.

Elections to the Chamber of Deputies were held on 19 May 1968 — the communists and socialists were able to increase their representation by 21 seats, while support for the CD, on the contrary, dropped significantly. At the same time, the parties to the right of the Democratic Christians, thanks to the joint coordination of actions, received significant popular support, especially in southern Italy, thanks to which the ruling coalition retained the majority. In addition, the PDSI, which did not want to cooperate with the communists, but also could not resume cooperation with the CD, found itself in a marginal position and showed the worst result in its history, losing half of its seats in parliament. On 24 June, the first "seaside government" (it: Governo balneare), Giovanni Leone, was formed, which had temporary powers for a while, while negotiations were underway between the main parties on the permanent composition of the cabinet.

Giulio Andreotti's second cabinet[]

On 12 December the government was again headed by Andreotti. Leone, who retired on 11 May 1969, replaced Antonio Segni as President of Italy, which again ensured the right wing of the CD control over both leading posts in the republic. A month later, on 15 June, the still not old Arturo Michelini, one of the architects of the center-right coalition, died. The new leader of the MSI was elected on 29 June, the head of the neo-fascist trade union CISNAL (it: Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Nazionali dei Lavoratori — Italian Confederation of National Labor Unions) Giovanni Roberti, a representative of the moderate wing of the party, who opposed any radical forms of participation in politics and for the final rejection of continuity Mussolini's ideology (he called himself a "national democrat"). The election of Roberti alienated many far-rightists from the MSI, who joined the ranks of the National Avant-Garde and the New Order, but nevertheless had a positive effect on the image of the movement, which in the eyes of other right-wing parties was gradually turning into an equal partner.

Milan business center

Andreotti's return to Palazzo Chigi coincided with the peak and, at the same time, the finale of the Italian economic miracle, which was ended by the international energy crisis. During this period, the growth rate continued to hold at the level of 5% per year, as a result of which, for a short time, the Italian economy even became the sixth economy in the world, overtaking the UK. The living conditions of the common population also improved radically: during the Hot Autumn, workers managed to achieve a 14% increase in wages, the number of televisions and private cars increased, the number of hotel visitors doubled, and the number of Italians involved in tourism quadrupled. Sports that were previously considered elite, such as water skiing, have become available. Studies have shown that even the average height of Italians has grown from 170 cm in twenty years to 174 cm.

Uprising in Bologna[]

The 1969 energy crisis led to the stagnation of the Italian economy and, as a result, a new wave of protest. On 12 December, there was a terrorist attack on Piazza Fontana in Milan, which killed 17 people — the government hastened to blame the leftist radicals, but later it was possible to establish the involvement of neo-fascists from the New Order and the Italian special services in the attack (the investigation was carried out until 2005). The emergence of political terrorism coincided with the next "war of the mafia" and the rise of the labor movement, during which the three largest trade unions united against the government — the communist General Italian Confederation of Labor (it: Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro; CGIL), the Social Democratic Italian Labor Union (it: Unione Italiana del Lavoro; UIL) and the Social Christian Italian Confederation of Workers' Trade Unions (it: Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori; CISL). Under these conditions, Andreotti proposed a draft administrative reform, which consisted in the creation of regions — the unification of several provinces, the boundaries of which were determined with the expectation that the provinces where the positions of the communists were strong were balanced by the provinces loyal to the ruling party. The corresponding law was adopted on 16 May 1970.

Demonstration of the radical left group "Potere Operaio"

On 17 January, the government announced the transfer of the capital of the Emilia-Romagna region from Bologna to Piacenza, which caused an explosion of discontent on the left - the region was a stronghold of the PCI, the mayors of Bologna since the fall of the fascist regime were exclusively communists, while in Piacenza the sympathies of the population were on the side of the CD. Thus, Andreotti hoped to strengthen the position of the ruling coalition at the most vulnerable point on the map of Italy. On 5 July, the mayor of Bologna, Guido Fanti, called at a rally to defend the status of the capital of the city, which served as a signal for the radicalization of the masses: anarchists, trotskyists, “new leftists” began to flock to Bologna from all over northern Italy, which is why at first a purely communist protest acquired the broadest coverage. On 13 July, workers and students began to erect barricades, and on 14 July, one of the leaders of the radicals, Alberto Franceschini, proclaimed the action of the Bolognese "the first step of the socialist revolution." The speech quickly turned into an uprising — every day there were fighting between the protesters and the police, the mayor's office officially supported the opposition's demands, and on 3 August, the Joint Committee for the Capital Bologna was formed, which actually took power over most of the city.

Nevertheless, despite the initial success, the Bolognese remained alone, since no performances of a comparable scale in other cities of Italy took place. In addition, if at first the actions of the rebels were unconditionally approved by the PCI, and even Pietro Ingrao came to speak in front of the protesters, later radicals, especially anarchists and Trotskyists, began to be promoted to the first roles in the uprising, which aroused fears among the leadership of the Communist Party. In addition, the ultra-right became more active, who often organized parallel demonstrations under nationalist slogans, campaigned among the workers, trying to win them over to their side, carried out provocations and terrorist attacks. An alarming signal was that the New Order militants were definitely hostile to the PCI activists and even set fire to the building of the party city committee, but at the same time they could act in concert with the anarchists and other left-wing radicals, considering them allies in destabilizing the situation in the country.

Uprising in Bologna

On 21 eptember, the police went to storm the barricades and this time they were able to inflict a decisive defeat on the rebels — by the end of the month, peace reigned in Bologna again. At the same time, many activists scattered across the cities of Northern Italy and tried to organize the struggle in a new place, as a result of which demonstrations did not subside throughout the autumn and winter of 1970 in Milan, Turin, Parma and other cities. According to official figures, 3 people died during the uprising, 190 police officers and 37 civilians were injured.

Divorce law[]

In the same year, the entire Italian society was almost split over the discussion in parliament of a draft law on divorce. Italy remained the country with one of the most conservative laws in the field of family and marriage — under the terms of the Lateran Agreements of 1929, this area remained in the office of the Catholic Church, which made it almost impossible to divorce. Even timid attempts to change this situation (for example, to allow divorce in the event of mental illness or a long prison sentence of one of the spouses) met with fierce resistance and were often rejected by parliamentarians outright. However, in 1965, Communist MP Loris Fortuna introduced a divorce bill to the Chamber of Deputies, supported by the extra-parliamentary Radical Party, which made the legalization of divorce a major requirement in its program. The radicals' agitation was a success among the broad popular masses, and in 1970 the Fortune bill was unexpectedly supported by liberal MP Antonio Baslini, whose party votes tipped the scales in favor of supporters of divorce. Despite the fact that the PLI, thanks to Malagoda, actually became conservative, unlike the CD and MSI, it defended the secular nature of the Italian state. Malagodi supported Baslini's initiative, which caused a storm of indignation among monarchists and neo-fascists — the “Great Right” actually collapsed, the Andreotti government lost its majority in parliament.

Ironically, the "family issue" has become a threat for the Christian Democrats much more dangerous than outright rebellion. At first, they intended to bring the issue of divorce to a referendum, hoping that the Catholic masses would preserve the sanctity of marriage by voting, forcing the liberals to reconcile, but sociological data showed that in this case, up to two-thirds of voters could support the right to divorce and make its legalization irreversible, therefore Andreotti was forced to change tactics. Once the issue was brought before parliament, in which the right no longer had the necessary majority, the prime minister had to look for an ally among the left. This led him to perhaps the most extravagant decision in his entire political career — the anti-communist Andreotti began negotiations with the Communist Party, inviting it to reconsider the Fortuna-Baslini bill, and unexpectedly received support from the leader of the left, Pietro Ingrao. Both politicians were well aware of the danger of the new law: Andreotti, he could cost the prime minister's chair, but Ingrao, who sought to attract Catholics to the side of the Communist Party, was afraid to alienate potential voters and become the unwitting culprit of the consolidation of the ultra-right. The result of these negotiations was “The Andreotti-Iotti compromise[3]”, according to which only civil marriage was allowed to dissolve — a church marriage, still recognized by the state, remained unshakable.

Pietro Ingrao and Giulio Andreotti in negotiations

A new divorce law was passed on 1 December 1970. Only monarchists and neo-fascists voted against, who perceived the compromise as a betrayal by the CD, even though the Vatican as a whole agreed to recognize the decision of the parliamentarians. Andreotti retained the post of Prime Minister, but now he was faced with the task of reviving the old coalition, which required no less effort.

Golpe Borghese[]

On the night of 7—8 December 1970, the entire political situation in Italy was almost turned upside down when several hundred ultra-right militants led by Prince Junio Valerio Borghese attempted a coup d'état. The conspirators seized the buildings of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Defense and were already preparing to take control of the office of the RAI radio company, arrest President Leone and carry out the murder of the chief of the Roman police, Angelo Vicari, when, unexpectedly, Borghese, after a phone call from an unknown person, ordered to cancel the coup. Nevertheless, it was not possible to hide the actions of the Borghezians from ordinary townspeople — in the next few days, the police received several messages at once about the movement of convoys and even tanks along the streets of Rome. Borghese himself fled to Spain shortly after the December events.

The press announced the prevention of the coup attempt only on 17 March 1971. A judicial investigation was organized, which, however, could not unequivocally prove the existence of a conspiracy and the involvement of the leadership of the army and special services in its preparation. The circumstances that forced Borghese to abandon his plans at the last minute also remained unclear. Only a few years later, information appeared that the conspiracy was being prepared in close cooperation with the US intelligence services and the leadership of the Christians Democrats, who hoped to use the threat of a fascist coup in order to rally around themselves former allies in the parliamentary coalition and, if lucky, push through the decision to vest Andreotti with emergency powers. In the 1990s, the testimony of Adriano Monti, who served as an intermediary between the Borghezians and Washington, was declassified, who directly pointed out the Italian prime minister's interest in the conspirators — Monti, in particular, claimed that the very phone call came from Gilberto Bernabei, then Andreotti's secretary.

MSI propaganda poster

Be that as it may, the disclosure of the conspiracy allowed the prime minister to strengthen his position: all parties condemned Borghese's actions, even the MSI publicly disowned him and urged its supporters not to succumb to provocations. The leadership of the Communist Party was also forced to call on the workers who continued strikes in a number of cities in Northern Italy to abandon the struggle for a while, so as not to destabilize the situation, as the neo-fascists would like. On 10 April, Giovanni Roberti agreed to re-enter the coalition without direct participation in the government, but made it clear that in the future his party does not intend to be content with "handouts" and will seek to provide her with ministerial seats.

Andreotti's fourth government lasted a year and a half without significant new crises. Nevertheless, the price paid by the prime minister for preserving a stable right-wing coalition was high: the main striking force that, in the event of a crisis, could defend the christian-democrat government — the neo-fascists — turned out to a split, its most "passionate" part passed into a deaf opposition, as to the CD, and to MSI. In addition, the Italian Catholics, the main support of the ruling party, were also disappointed. Seeing that the "defenders of the church" for the sake of power can easily change the interests of this very church, religiously minded citizens more and more succumbed to the agitation of right-wing and left-wing radicals, which caused the ground to slip from under the feet of the CD.

Oscar Luigi Scalfaro's first cabinet[]

On 25—27 February 1972, the congress of the Democratic Party of Monarchical Unity Alfredo Covelli was held, at which it was decided to merge it with the MSI into a single national-conservative party called the Italian Social Movement — National Right (it: Movimento Sociale Italiano - Destra Nazionale; MSI-DN). On 10 July the union was legally consolidated, and at the next congress of the MSI in January 1973, Covelli became the honorary chairman of the movement. By 13 July, an agreement was reached between the neo-fascists (by this time they were preferred to be called the more "politically correct" term "nationalists") and the Democratic Christians: Andreotti, because of his support for the divorce law, had to give up the post of prime minister in favor of a representative of another faction inside CD (also right-wing, but hostile to him) — Oscar Luigi Scalfaro.

Andreotti and Scalfaro at the CD Congress

Scalfaro was a follower of Mario Scelba and fought to the end both against the Fortuna-Baslini law and against the “Andreotti-Iotti compromise”, considering any agreements with the communists unacceptable. In the government, he was constantly on the sidelines, and therefore remained a little-known figure in Italian politics, which suited Roberti, Malagoda and Pacciardi, who, thanks to their experience, could count on leading roles in the government. Since parliamentary elections were due in the spring of 1973, the Scalfaro government should have existed for less than a year, and the CD was quite happy with this situation.

The inclusion of the ultra-right in the government meant the end of the Centro-Desta era — the new four-party coalition received the unofficial name of Cuadripartito, which was later extended to the entire period in the history of the Italian Republic, which began in 1972. If in the ranks of the MSI, 13 July was declared the day of the "Historical Compromise", the left compared the actions of the Christians Democrats with the "March on Rome" in 1922 and the "fascist counter-revolution". Ingrao, elected as the new secretary general of the PCI on 16 March 1972, called on his supporters to go on a national strike against the government: workers and students in Venice, Naples, Rome, Milan, Turin and other cities took part in demonstrations of thousands, which quickly grew into bloody clashes with neo-fascists. On 3 August, in the capital, the police were forced to open fire on the crowd, in response, left-wing radicals pelted the police with homemade bombs and Molotov cocktails. One policeman was killed, five people were injured. The peak of the confrontation came at the end of October, on the 50th anniversary of Mussolini's coming to power. By this time, extremists on both sides had turned to overtly terrorist methods of struggle — communists from the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse) and Continuous Struggle (Lotta Continua) groups kidnapped prominent corporate workers or blew up police stations, and the radical fascists killed union leaders.

Frightened by the outbreak of street violence, many Italians felt it good to support the government. In winter, the strikes subsided. Nevertheless, the protest, and without that did not disappear for a long time since 1965, now began to acquire the most cruel and gloomy colors. The seventies in Italy were called “Years of Lead” (it: Anni di piombo), and street confrontation between the left and right was often characterized as a “civil war of low intensity”. Political radicalization was superimposed on economic problems that forced the government to resort to austerity. One of the measures was a program to restrict the use of transport, which received the unofficial name "On Sundays on foot" (it: Domenica a piedi).

Emilio Colombo with German Chancellor Willy Brandt

Emilio Colombo's cabinet[]

Terrorist attack in Brescia

At the next elections, the alignment in parliament turned out to be approximately the same as five years ago. The only major change was the almost twofold increase in the votes cast for the MSI — the inclusion of nationalists in the government favorably affected the image of their party, thanks to which they reached their historic high, gaining almost 10% of the seats in parliament. The CD's strategy turned out to be a winning one: despite the fact that the representation of other members of the ruling coalition decreased, they still had a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Immediately after the elections, the next "transition government" was headed by Mariano Rumor, and on 5 November, negotiations between the members of "Cuadripartito" ended with the formation of the cabinet of Emilio Colombo. He remained in power for about a year and a half, and as a result of internal intrigues within the CD, he was replaced by the next Andreotti government. Colombo's time in power is usually seen as a prologue to a full-scale crisis of the entire political system of the Italian Republic: the world was rapidly "leveled" — a radical democrat George McGovern came to power in the United States, on 25 April 1974, the "Carnation Revolution" ended the fascist regime in Portugal, in In the same year, the Vietnam War ended with the unification of the country under the rule of the Communists, on 23 July, the military junta in Greece fell, and on 9 January 1975, Erich Apel in Germany formed a government with the participation of the SED. In these conditions, Italy remained one of the few countries in Europe, where, on the contrary, the government shifted more and more "to the right", which every year put it in an increasingly ambiguous position.

On 28 May 1974, New Order militants staged a terrorist attack in Brescia, killing 8 and wounding about 100 communist demonstrators. On 4 August, an express train in San Benedetto was blown up — 12 people were killed, 50 more were injured. In the current situation, when legal ultra-right organizations were part of the government and themselves adopted repressive laws, "black terrorism" increasingly merged with the anarchist movement: from apologists for a strong state, Italian neo-fascists turned into the main enemies of this very state. To discredit the left, militants Pino Rauti and Stefano Delle Chiaie often infiltrated their structures, organizing provocations and provoking clashes with the police. The leadership of the left-wing radical groups oriented towards the PCI was forced to change tactics, abandoning the methods of individual terror in favor of mass actions and strikes — those groups that continued to carry out terrorist activities were henceforth considered by the leadership of the Communist Party as "accomplices of the fascists."

Giulio Andreotti's third cabinet[]

US Vice President Edward Kennedy with Italian President Giovanni Leone

The upsurge in street violence once again allowed Andreotti to lead the Council of Ministers. Nationalists have come to terms with the "traitor to the church" in the prime minister's chair, as his experience and influence were needed to lead the country out of the political and economic crisis. Thanks to Andreotti, the "Reale Law" of 22 May 1975 was passed, significantly expanding the powers of the police, allowing citizens to be arrested for four days without charge and the use of firearms to prevent crime.

Tough measures allowed Andreotti to contain street violence for a while, but he soon faced such a crisis, which he was no longer able to solve. In early 1976, a major corruption scandal erupted when the Foreign Affairs Committee of the US Senate made public the fact that prominent politicians in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Japan had received bribes from Lockheed Airlines, which sold its civil and military aircraft to these countries. Almost all the proven facts of receiving bribes by the leadership of the Italian Ministry of Defense occurred in the period from 1968 to 1972, when the government was headed by Andreotti, so he soon found himself at the center of a judicial investigation. Indirectly, the scandal hit President Leone, who was forced to refuse to nominate himself for a second term. On 20 June, the government resigned, the ruling coalition was disunited for some time, and the CD had to hastily form a new cabinet, lacking the necessary majority.

The trials dragged on for three years — two ex-ministers, one general, several party functionaries and leaders of the largest machine-building companies were in the dock. Andreotti managed to avoid court that time, but, as it turned out, the troubles of his party were just beginning. The society saw with its own eyes how corrupt the entire political system of the country was, which came in handy for the left, primarily the PCI, which fanned the scandal in the controlled press. The elections in Sicily, in which the communists, traditionally receiving little support in the conservative south, won nearly a million votes, beating the MSI and forming the second largest faction in the regional assembly, an indication of the radical change in voters' sympathy. The number of the ranks of the Communist Party by the end of the year exceeded 2 million people — thus it became the largest party in Italy and the largest communist party in the Western world; at the same time, the number of CD members as a result of the scandal decreased to 1.2 million people.

Arnaldo Forlani's cabinet[]

Oscar Luigi Scalfaro's second cabinet[]

Notes[]

to be continued...

Credit[]

The universe "Socialism with Human Face" is the intellectual property of his author Huey Long on the site Альтернативная История. I do here only the translation and the identical retransciption in English of his work. To ask him questions and / or see his other works go to his profile.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![CD-1.png (378 KB) Ist convocation of Chamber of Deputies (1948—1953) People's Democratic Front (PCI + PSI): 183 seats Unità Socialista: 33 seats PRI: 9 seats Peasants' Party of Italy: 1 seat Automists[2]: 4 seats CD: 305 seats PLI: 19 seats Monarchists: 14 seats MSI: 6 seats](https://static.wikia.nocookie.net/althistory/images/1/14/CD-1.png/revision/latest/scale-to-width-down/338?cb=20210129084212)