Philip VII (French: Philippe VII; 24 August 1838 – 8 September 1894) - King of France, second representative of Orléans dynasty on French throne, grandson of Louis Philippe I.

The reign of Philip VII was marked by the beginning of expansion of the French Colonial Empire which had a significant impact on the internal situation of the restored monarchy. Despite his short reign, reforms were initiated in order to catch up with the delay taken by the reign of Henry V and started an era of institutional stability in France.

The Count of Paris[]

Prince Louis Philippe[1]Albert d'Orléans was born on 24 August 1838 at the Tuileries Palace in Paris, residence of the royal family of France. Son of Prince Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans and Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the Princess Royal give to all children of both sexes born in Paris on the same day as her son are issued a savings book with a first stake of one hundred francs. After having considered for a moment to name him "Prince of Algiers", his grandfather, the King of the French Louis Philippe I, resuscitates for him the title of count of Paris, worn in the IXth century by Odo, King of West Francia one of the founders of the Capetian dynasty. The initiative is intended to remind other European dynasties of the seniority of the House of Orleans at the same time as its attachment to the French capital, to which the Bourbons of the elder branch had preferred Versailles.

Louis Philippe Albert d'Orléans, Count of Paris (in center) with his parents and brother

In France, the arrival of an heir within the royal family seems, at first, to consolidate the throne of July and to make people forget the difficulty that Louis Philippe and his family had represented to find a bride for the prince royal. Considered by other European dynasties as a son of a usurper, Ferdinand Philippe d'Orléans had to endure the humiliating refusal of several princesses of the continent before finding an agreement to marry him. However, the young girl in question, Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, comes from an unglorious German dynasty and her union with the heir to the French crown has been accompanied by perfidious comments abroad[2]. The coming into the world of the Count of Paris therefore allows the royal family to forget the difficult period they have just gone through and to project themselves fearlessly into the future.

The baptism of the Count of Paris on 2 May 1841, gave rise to a lavish ceremony in Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral. Beyond the festivities, the event brings the July monarchy closer to the Catholic Church. Since the death of the very legitimist Mgr de Quélen on 31 December 1839, and his replacement by Mgr Affre at the head of the archbishopric of Paris from 6 August 1840, the Catholic clergy has indeed shown itself to be much more open towards live with the Orléans and no longer balks at associating with the strong moments of the dynasty.

The prince’s early years were happy and he grew up in the midst of a loving and caring family. From December 1840, his mother, Princess Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, imported the custom of the Christmas tree from Germany for him. Despite everything, the child also spends long periods without seeing his father, especially when the latter went to visit Algeria in 1839 and returned there in the spring of 1840 to continue the fight against the forces of Emir Abdelkader.

Child heir of Louis Philippe[]

The life of the young Count of Paris changed on 13 July 1842. That day, his father, Prince Ferdinand Philippe d'Orléans, died of a fractured skull in a convertible accident, while he was traveling to visit to Neuilly, to find Queen Maria Amelia and King Louis Philippe. Barely four years old, the child then becomes the new heir to the throne and receives, as a result, the title of Prince Royal.

Death of Prince Ferdinand Philippe d'Orléans

With the death of the Duke of Orleans, the question of the survival of the July monarchy quickly arises. In 1842, the sovereign, whose policy is more and more reactionary, is indeed sixty-nine years old and it is unlikely that he will live until the majority of his grandson. The Chambers may therefore vote to lower the majority of the Prince Royal from twenty-one to eighteen, the regime must appoint a regent to effect the transition between the two reigns. Several choices were then offered to the king: his four surviving sons, the Duke of Nemours, the Prince of Joinville, the Duke of Aumale and the Duke of Montpensier, or his daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Orléans. According to dynastic rule and the testament of the Duke of Orleans, the monarch chooses his second son, Nemours, as eventual regent. However, this one has the reputation of being the most conservative of Orleans and the royal decision is very badly received by the people, who would prefer to see Joinville, Aumale or the Duchess of Orleans at the head of the country.

The death of the Duke of Orleans also reinforces the need to give a careful education to the Count of Paris in order to prepare him for his role as heir to the throne. In 1843, the prince was therefore entrusted to the care of Jacques Regnier, a future member of the Institut de France, and to those of Etienne Allaire.

The Revolution of 1848[]

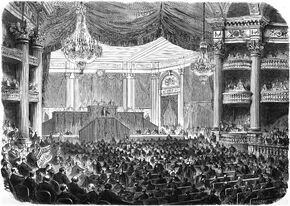

The Duchess of Orleans at the Palais Bourbon to ask for the regency

From 1846, the crisis fell on the July Monarchy. Economic difficulties and a series of financial scandals discredit the king and his government while the "banquets campaign" (French:Campagne des banquets) illustrates the renewed popularity of the republican movement. In February 1848, the decision of François Guizot, the president of the Council, to ban the last of the banquets crystallized the opposition and riots occurred in Paris from the 22 February. The demonstrations quickly grew and turned into revolution. The 23 February, Louis Philippe sent Guizot away, which initially seemed to calm the crowds. But, after a few hours of calm, unrest resumed and the Army fired on demonstrators. Overwhelmed by revolutionaries and refusing to shed more blood, King Louis-Philippe abdicated on 24 February in favor of his grandson the Count of Paris, then nine years old. Aware of his unpopularity, the Duke of Nemours for his part decides to give up the regency in favor of his sister-in-law, who enjoys a reputation as a liberal.

At the beginning of the afternoon of the 24, the Duchess of Orleans therefore went to the Palais Bourbon with her children and her brother-in-law Nemours to invest her eldest son there and to be proclaimed regent. In their majority, the deputies seem favorable to this solution and André Dupin asks the Chamber to take note of the acclamations which the Duchess receives. A discussion, led by Odilon Barrot, then begins on the law of regency. But the voices of supporters of the monarchy are gradually covered by the boos of the public who came to attend the deliberations. An armed crowd invades the debating hall while the Republican deputies Ledru-Rollin, Crémieux and Lamartine seize the platform to demand a provisional government. The Orléans are then brutally evacuated from the Chamber of Deputies and, in the stampede that follows, the Princess of Mecklenburg is separated from her children. Anxious, the princess took three days to locate the little Duke of Chartres, who had been taken in by a Parisian baker. Once reunited, the Duchess of Orleans and her children set off for exile. At the same time, the Second Republic is proclaimed in France.

The exile[]

In the aftermath of the Revolution of 1848, the members of the royal family took turns to win abroad while the provisional government voted to ban Orléans on 26 May. Louis Philippe and Maria Amelia thus settled in the United Kingdom with several of their children and grandchildren. The former sovereigns established their residence at the Château de Claremont, property of King Leopold I of Belgium[3], himself son-in-law of Louis Philippe and uncle of the Count of Paris. For her part, the Duchess of Orleans prefers to live with her children in Germany, in the Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Wounded by the behavior of the king and the queen towards her during the revolutionary days, the princess indeed prefers to move away from her in-laws.

Meeting of the Count of Paris (and the Orleans) with the Count of Chambord

At the same time, the financial situation of Louis Philippe and his family is becoming increasingly precarious. Immediately after the vote for the banishment of the Orleans, the provisional government sequestered the property of the fallen monarch and his relatives. However, without own resources, the Duchess of Orleans and her children are totally dependent on the former sovereigns, a situation which will worsen in January 1852. After two years of quarrel, Princess Helene finally reconciled with her in-laws and, from the spring of 1850, the Count of Paris, the Duke of Chartres and their mother regularly visited England. It was also in London that the young pretender Orleanist made his first communion in the presence of his grandfather on 20 July 1850.

In France, the advent of the Republic and the election by universal suffrage of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte to the presidency have prompted monarchists to question their political strategies. More and more Orleanists want Louis Philippe and his family to join the grandson of Charles X, who for the legitimists is the representative of dynastic legitimacy. However, for their part, the Orleans are not unanimous. If the former sovereigns seem to recognize little by little the need for the merger of the two royalist currents, the mother of the Count of Paris strongly opposes the recognition of the grandson of Charles X – Henry, Count of Chambord – as heir of the crown. Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin is moreover deeply shocked by the letter sent to her by her father-in-law and in which the latter writes, about the succession to the throne:

| “ | My grandson will never be able to reign in the same way and under the same conditions as I who ended up failing. He can only reign as a legitimate king. There are several ways for him to become a legitimate king: if the Duke of Bordeaux died, if the Duke of Bordeaux abdicated, if the Duke of Bordeaux reigned but had no children, Paris will then become a legitimate king. He must remain in a position for all these chances. | ” |

Head of the House of Orléans[]

On 26 August 1850 after several days of agony, the ex-king Louis Philippe died alongside his wife and several of his children and grandchildren at the age of sixty. seventeen years. For the Orleanists, the Count of Paris then officially became his successor but very few, in France, believed in the possibility of a restoration embodied by a twelve-year-old child, especially since after the plebiscite of 21 November 1852, the Second Empire is set up.

In July 1857, the Duchess of Orleans and her sons permanently left Germany to settle in England and be closer to Maria Amelia. The family then rented a country house in Richmond, an hour from Claremont, where the old queen still resides. In this new residence, the Count of Paris continued his training and received, among other things, private lessons in law from the magistrate Rodolphe Dareste de la Chavanne. In May 1858, the Duke of Chartres contracted the flu and his mother was also affected. Soon, the princess’s health worsened and she died on 17 May. The loss of his mother does not stop the thirst for experience of the Count of Paris. After trying to enter the Military School of Turin, to follow his brother, he undertook with the latter a trip to the East in November 1859 where he visited Greece, Istanbul, Jerusalem, Mount Sinai, Egypt and Syria. At 21 year-old Count of Paris therefore found himself an orphan and settled alongside his grandmother, until her death in 1866.

The Count of Paris in Union military uniform

In September 1861, François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, left for the United States to accompany his son, the Duke of Penthièvre, who wished to take studies at the American Navy School. Tired of the inaction to which their status of exiles condemn them, the Count of Paris and his brother decide to accompany their uncle and their cousin. On the spot, the princes were enthusiastic about the anti-slavery movement and were quick to engage in the Civil War, which shook the United States. Appointed staff officer of the command in chief of the federal armies, George McClellan, the count of Paris thus fights, with his brother, the Southerners at the battle of Gaines' Mill, on 27 June 1862, while the prince of Joinville takes part in the Potomac campaign. The two young Orléans princes distinguished themselves by their courage and their understanding of matters of war.

The presence of the two princes is however a problem for the government in Washington and the French government. The relationship between the two already tense due to the Mexican expedition undertaken by France in 1861, this deteriorates with the unofficial support given by the French Empire to the Confederation of American States and the military exploits of the Orléans princes increase the difference between the two countries. In front of the pressure, the Count of Paris and the Duke of Chartres submit their resignations to the staff on 2 July 1862. Their resignation was accepted with regret by the general-in-chief, as well as by President Lincoln; and they embarked for Europe. From this stay in the United States, the Count of Paris brings back a History of the Civil War in America (French:Histoire de la Guerre civile en Amérique) in seven volumes and his uncle, a large number of watercolors illustrating the conflict.

Return in France[]

After the declaration of the Franco-Prussian war, the French armies are defeated. The princes had asked to serve in the army on news of the disasters, which they had been refused by the imperial government first, then by the provisional republican government. The Duke of Chartres succeeded in enlisting and made the campaign of France under the name of Robert Le Fort. When the Second Empire collapsed in 1870, and the first law of exile affecting the Orleans was abolished on 8 June 1871, the Count of Paris returned to France. A few months later, on 9 December 1871, the decrees of confiscation of the property of the royal family put in place by Napoleon III in 1852 were abolished. Philippe d'Orléans then took back possession of the castles of Amboise, Eu and Randan. In France, the count of Paris and his family share their existence between their provincial residences and the capital.

The elected assembly of 1871 repeals the banishment laws of Orleans.

As soon as he returned to the country, the prince frequented the circles of power and was received by President Adolphe Thiers at the Palace of Versailles on 1 July. The interview is cordial but, in private, the former president of the Council Minister of Louis Philippe does not hide his contempt for the leader of Orléans. To one of his close friends, Thiers declared, in fact, about the heir to the throne: "Ten paces away, he looks like a German, three of a fool".

The Monarchical Fusion[]

Despite his political activities, the prince has no plans to ascend the throne yet. Aware that the Count of Chambord is supported by more monarchists than he himself, the Count of Paris seeks to get closer to his cousin. Henri d'Artois having no children, the leader of the Orleans is indeed convinced that a legitimist restoration would make him the Dauphin and would strengthen the monarchist camp against the Republicans and Bonapartists. After a visit in Algeria at the beginning of May 1873, the events of May and April 1873 haunt the return of the Count of Paris to France. On 24 May 1873, Adolphe Thiers was transferred from the head of the French government and state by the monarchist assembly replaced by Marshal Patrice de MacMahon, also monarchist and supporter of the return of royalty to France. Happy with this news, the Count of Paris saw there the certain restoration of the monarchy and on 1 June, he met the Marshal-President.

After the unsuccessful sending of several emissaries to the Count of Chambord, the Count of Paris decides to go himself to Frohsdorf in order to officially affirm his submission to the eldest Capetian. On 5 August 1873, the prince thus declared to his cousin:

The Count of Chambord recognized by Orléans as only pretender of throne

| “ | My cousin, in greeting today the head of our house, in my name, as in the name of my family, I come to recognize at the same time the monarchical principle of which you are the only representative in France. The day when our country understands that its salvation is in the restoration of the monarchy, be convinced that you will not find a competitor to the throne, neither in me, nor in any member of my family. | ” |

With these words, the Count de Chambord interrupts him, kisses him and takes him to his private living room, where the two cousins have an interview in which nothing filters but this sentence from Henri: "You did a good deed. God will take this into account”. The fusion of the two monarchist currents and the mutual recognition of the two princes as head of the family and heir therefore seem total. However, the reconciliation of the two branches of the royal family does not immediately lead to the expected restoration. On 12 August 1873, the Count of Paris announced the monarchical fusion to the President of the Republic, the legitimist Patrice de Mac Mahon, and asked him to convene the Assembly in extraordinary session in order to proclaim the Count of Chambord king. But, although a monarchist, the marshal refuses because of the will of the pretender to restore the white flag and not to maintain the tricolor as a national symbol.

Several actions are therefore carried out by supporters of the Restoration to try to convince the grandson of Charles X of the need, according to them, to abandon the white flag and to accept the parliamentary system. In October 1873, the deputy Charles Chesnelong was thus mandated by the monarchist group of the House to reach an agreement with the pretender. On 14 October 1873, the monarchist deputy and the Comte de Chambord meet, and reach a satisfactory agreement. On 5 November 1873, at 9:50 am — at the first session of the Assembly — out of a total of 673 deputies present in the Assembly for the vote, 424 votes for the royalist regime, 209 against and 42 abstention, is voted a text prepared by the commission with as first article that "the national, hereditary and constitutional monarchy is the government of France". The monarchy in France is restored.

Dauphin of France[]

An uncertain heir[]

Battles of influences[]

Leader of the monarchical party[]

King of France[]

Consolidation of monarchy[]

Main article: Le Ralliement

Foreign policy[]

The extension of alliances[]

Main articles: Mediterranean Entente

Colonial expansion[]

Main articles: Second French Colonial Empire

Domestic policy[]

Last Years[]

Family[]

Ancestors[]

| Father: Prince Ferdinand Philippe of Orleans |

Paternal grandfather: Louis Philippe I, King of the French |

Paternal great-grandfather: Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans |

| Paternal great-grandmother: Louise Marie Adélaïde of Bourbon | ||

| Paternal grandmother: Maria Amelia of Bourbon-Two Sicilies |

Paternal great-grandfather: Ferdinand I, King of the Two Sicilies | |

| Paternal great-grandmother: Maria Carolina of Austria | ||

| Mother: Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

Maternal grandfather: Frederick Louis, Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

Maternal great-grandfather: Frederick Francis I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| Maternal great-grandmother: Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg | ||

| Maternal grandmother: Caroline Louise of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach |

Maternal great-grandfather: Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach | |

| Maternal great-grandmother: Louise of Hesse-Darmstadt |

Children[]

Result of reign[]

Notes[]

- ↑ His usual first name was "Louis Philippe" until 1883.

- ↑ Informed of the marriage plan, Tsar Nicolas I of Russia declared that “such a small marriage is not worth preventing”.

- ↑ Widower, by first marriage, of Charlotte of Wales, Princess of Wales, King Leopold I of Belgium retained the enjoyment of his English home.

| ||||||||||||||||