Unitatis ("Unity") | |||||||

| Anthem | "God Save the Queen" | ||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

London | ||||||

| Other cities | Toronto, Sydney, Melbourne, Cape Town, Durban, Seattle, Montréal, Auckland, Calgary | ||||||

| Language official |

English | ||||||

| others | French, Zulu, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Creole, Fijian, Hindi, Spanish, Gilbertese, Māori, Tuvaluan | ||||||

| Religion | Christianity (especially Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, Presbyterianism,Methodism) | ||||||

| Ethnic Groups main |

White | ||||||

| others | Black (Black African, Afro-Caribbean), Asian (Indian, East Asian), Polynesian, First Nations, Australian Aboriginal | ||||||

| Demonym | British | ||||||

| Government | Confederal Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||

| Queen | Elizabeth II | ||||||

| Prime Minister | Stephen Harper (Federalist) | ||||||

| Area | 8,442,756 sq mi | ||||||

| Population | 173,869,911 (2016 Census, excluding colonies) | ||||||

| GDP Total: |

£64.619 trillion (nominal) | ||||||

| per capita | £371,653 (nominal) | ||||||

| Established | 17 October 1912 | ||||||

| Currency | British Pound Sterling (GBP; £); Canadian Dollar (CAD; $); South African Pound (SAP; £); Australian Dollar (AUD; $); Cascadian Dollar (CSD; $); West Indian Dollar (WID; $); Irish Pound (IRP; £); New Zealand Dollar (NZD; $); Fijian Dollar (FJD; $); Mauritian Rupee (MUR; ₨); Kiribati and Tuvalu Dollar (KTD; $) | ||||||

| Organizations | NSTO, G7, Commonwealth of Nations | ||||||

The United Kingdom of the British Empire, more commonly referred to as the United Kingdom or the UK, is a pluricontinental superstate. With a territory of 8,442,756 square miles in the British Isles, North America, Africa, and Oceania, it is the largest sovereign state in the word by area; and is the seventh-largest by population with almost 174 million inhabitants in the 2016 Census. It has coastlines on all four of the world's oceans, and shares borders with Brazil, Central America, Lesotho, Mexico, Namibia, the Republic of South Africa, Spain, Suriname, Swaziland, Venezuela, and the United States.

The UK is a Confederal Constitutional Monarchy and parliamentary democracy. The current Monarch is Queen Elizabeth II, while the current Prime Minister is Stephen Harper of the Federalist Party. The capital and largest city is London, with a population of approximately ten million, the main financial and cultural center of the country. Other prominent cities include Toronto, Sydney, and Seattle. In general, the country tends toward urbanisation, with significant tracts of unpopulated land. As a pluricontinental nation, climate and environment are highly variable, ranging from the Canadian Arctic to the Australian Outback, and from the temperate climate of the British Isles to the tropical climate of the West Indies.

The UK is a confederation of two Realms (Great Britain, Ireland), and twelve Dominions (Australia, Canada, Cascadia, Fiji, Gibraltar, Kiribati and Tuvalu, Mauritius, Newfoundland, New Zealand, Seychelles, Union of South Africa, West Indies), collectively referred to as Constituent States. These are themselves sovereign states with almost complete control of their internal affairs. The Imperial Parliament in Westminster has authority in the areas of foreign relations, defense, trade, and the eight remaining colonies.

Formed by the Imperial Convention and subsequent Constitution of 1912, the UK has been the primary global power since its genesis. Allied with Germany since 1904, it was able to remain neutral in the Great War and avoided much of the War's negative consequences. The 1920s saw sustained economic growth and a heyday of almost unquestioned power. This was dampened by the rise of Syndicalism, which was viewed with alarm by the British and their allies. To counter Syndicalist influence, the North Sea Treaty Organisation was formed, and the Cold War against the Pact of Steel began. All this happened in the midst of a wave of decolonisation, whereby the colonial holdings of the Empire were largely abandoned and the nation's global prestige was lowered. While earlier Cold War governments favoured an aggressive foreign policy, the government of Edward Heath began a policy of dialogue with the Pact of Steel that was continued by his successors. This policy was reversed by Margaret Thatcher, the first female Prime Minister, who began an arms race with the Syndicalist bloc in order to drain them financially. The Syndicalist collapse in 1992 was largely attributed to Thatcher, who resigned in triumph.

The UK is a developed country, with an estimated nominal GDP of almost £65 trillion; making it the largest economy in the world. The British economy is highly diversified, with a base in natural resources but significant manufacturing and service sectors.

History[]

Writing a history of the UK can be problematic, as it is a pluricontinental union which encompasses the history of many different regions. Additionally, the UK is viewed, in legal contexts, as the successor state of the former United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This was in turn the successor of Great Britain and Ireland; the former of which was also the successor of England and Scotland. This section will attempt to be as broad as possible, but will inevitably focus on England during the pre-union era.

Prehistory and Antiquity[]

Human habitation in the regions that would become the modern UK dates back millions of years, and in the British Isles to about 800,000 years. After significant cultural developments in the Megalithic era, such as the building of Stonehenge, the region was overwhelmed by Celts, who subsequently developed into three main groups: the Britons south of the Firth of Forth, the Picts north of it, and the Gaels in Ireland.

Stonehenge, a relic of the Megalithic era

Roman interest in Britain began with Julius Caesar, but did not lead to any significant conquests until AD 43. The Romans conquered most of what is now England and Wales by about AD 60, briefly halted by a revolt led by the warrior-queen Boudica. The greatest expansion took place during the reign of Antonius Pius, when much of southern Scotland was Roman territory. However, in subsequent years the Romans would retreat from that extent. The Roman hold on Britain was significant, and Constantine the Great began his rise to power from a British base. But as the Western Roman Empire went into decline, the area collapsed into political instability. Into this vacuum entered the Anglo-Saxons.

Anglo-Saxon era[]

The Sutton Hoo helmet, a notable example of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship

The Anglo-Saxons, a Germanic group originating in what is now Frisia, began to invade and subjugate the area in the sixth century. Precisely why they began arriving is subject to debate, as is the completeness of settlement, but what is certain is that the Anglo-Saxons permanently changed the culture of England by the introduction of their language, Old English. Initially pagan, they were gradually converted to Christianity, starting with the missionary efforts of Augustine of Canterbury in 597. The Anglo-Saxons were divided into nine kingdoms, of which Mercia was initially the most powerful.

This supremacy was destroyed by the Viking invasion in the Ninth century, which subjugated most of the north of England to the Danelaw, an area of Viking dominance and settlement. Anglo-Saxon opposition centered around the Kingdom of Wessex, where Alfred the Great rose to prominence by his successful resistance. Under his son, Æthelstan, Wessex was able to conquer much of the Danelaw and establish the Kingdom of England. This period of dominance eventually faded, and by 1016, the Danish King Cnut was able to seize the throne for himself. A brief period of native rule was inaugurated by Edward the Confessor in 1046, but his death left a succession crisis in which three men claimed the throne. One of them was Duke William of Normandy.

High Mediaeval England[]

In 1066, William defeated Harold, the last remaining claimant to the throne, at the Battle of Hastings, and became King of England. William eventually subdued the entire country with the help of his barons, and formed a Francophone Norman aristocracy that dominated the country for centuries to come. He also introduced the feudal system, and a radical centralisation of the English state. The Anglo-Norman Empire William created lasted beyond his death, but crumbled in 1135 when a devastating Civil War over the succession broke out.

A copy of the Magna Carta

By 1154, the War was settled, and Henry II added England to his already considerable holdings in France. As part of the Angevin Empire, England enjoyed much prestige, especially under the reign of Richard the Lionheart, notable leader in the Crusades. But when Richard died, his brother John's inferior military skill led to loss of much French territory, and an argument with the Pope led to his excommunication and all England being placed under Interdict.

By 1215, the incensed barons forced John to sign the Magna Carta, a document that redressed many of their grievances and significantly reduced the power of the Monarch. While John tried to repeal it, the barons persisted in their support. His successor, Henry III, would face heavy baronial opposition; causing Simon de Montfort, leader of the barons, to effectively rule England for about a year. While he did not last long as a ruler, he summoned two Parliaments, one of which went so far as to include commoners from the towns. As such, he is regarded as the father of the British parliamentary tradition, and the Magna Carta is regarded as the foundation of the British constitution.

Late Mediaeval England and the Wars of the Roses[]

Into this chaos stepped Edward I, who inherited the throne in 1272. Pursuing an expansionist policy, he

Depiction of the Hundred Years War

conquered Wales, solidified the English hold on Ireland, and attempted to install a puppet regime in Scotland. While his son Edward II was a much less able ruler, his grandson Edward III proved worthy of his grandfather, and became a powerful ruler. Disputes over the territory of Gascony and the succession to the French throne led to the Hundred Years War with France; initially the English had the advantage, but this gradually was reversed, and the French eventually triumphed.

Defeat abroad was coupled with problems at home: the Great Famine, the Black Death, and the Peasant's Revolt all occurred in this period. When King Richard II was overthrown in 1399 by Henry Bolingbroke, it began a period of dynastic tension that came to a head in 1455, when Henry VI was deposed. This sparked a conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, where the houses of Lancaster and York both claimed the throne and fought each other bitterly to gain it. In 1485, Henry Tudor was able to overthrow the unpopular Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, ending the Wars of the Roses. This accomplished, Henry set himself to the task of rebuilding England.

Tudor Era[]

Henry VII's reign focused on economic development and conciliation between the houses of York and Lancaster (as the Lancastrian heir, he married Elizabeth of York, and thus cemented his claim to the throne).

The Elizabethan age was a time of cultural and political growth, all presided over by the beloved Queen Elizabeth I

His son, Henry VIII, embraced the ideals of the Renaissance and worked to modernise England. Though initially a supporter of the Pope, he pragmatically embraced the Reformation when he was refused an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and founded the Church of England. Henry left a troubled legacy of religious disputes and an unstable succession, and his changes were almost reversed by his daughter Mary, who attempted to forcibly reconvert England to Catholicism. Her heavy-handedness, however, had the opposite of the desired effect, and when she died her Protestant sister Elizabeth returned things to the status quo ante.

Elizabethan England saw both cultural flourishing, exemplified by the work of William Shakespeare, still considered the greatest writer in the English language. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 confirmed England's rising status as a naval power, and Sir Francis Drake's escapades against the Spanish were a significant source of national pride. Colonial expansion had begun as early as John Cabot's voyage to Newfoundland in 1497, but Elizabethan England began the first real attempts at settler colonialism. While the Roanoke colony was a dismal failure, it planted the seeds for what would become the British Empire, and thereby the modern United Kingdom.

Jacobean Era and the Civil War[]

When Elizabeth died in 1603, she was succeeded by her relative James VI of Scotland. At first, this was welcomed, as it united all of the British Isles under one crown and placed the country in Protestant hands. James, however, was used to the more amenable Scottish Parliament, and was not prepared for the robust parliamentary tradition that had developed in the Tudor era. He was unable to succeed in uniting his three kingdoms into one, as he wished; and though a Calvinist, he quickly became enemies with the Calvinistic Puritan movement within the Church of England. The Gunpowder Plot briefly unified the nation in anti-Catholic sentiment, but this unity was short-lived and James gradually lost his popularity. Two significant achievements, however, came out of his troubled reign: the Authorised Version, or King James Version, which provided a commonly agreed-upon English translation of the Bible for centuries to come; and the settlement at Jamestown, which not only survived but paved the way for further colonial expansion in the future.

Oliver Cromwell led the Parliamentarians in standing up to Charles I's authoritarianism, but ironically became an autocrat himself

Undoubtedly Charles I succeeded his father at an inopportune time, but he compounded his problems by attempting to consolidate his power at the expense of Parliament. Parliament fought back with the Petition of Right, which claimed severely limited powers for the King; the King responded by proroguing Parliament and ruling without them until 1640. A poor financial situation and religious tensions in Scotland forced Charles to eventually summon a Parliament, which forced him to comply with their wishes in exchange for funding.

Eventually, Charles grew tired of this and attempted to arrest five members of the House of Commons; this ill-conceived action provoked Civil War. The Parliamentarians under Oliver Cromwell quickly crushed the Royalists, and in 1649 Charles was tried and executed. A republic, the Commonwealth of England, was declared, but this degenerated into chaos. Cromwell stepped in to become Lord Protector (King in all but name), and led an efficient, militaristic Puritan state. When he died, however, the Protectorate fell apart, and the Monarchy under Charles II was restored.

Glorious Revolution and the English Empire[]

Charles II favoured a lenient attitude toward parliament, but when he died his Catholic brother James II tired to reassert the royal prerogatives his father had attempted to wield. A believer in the divine right of kings, James' autocratic leanings and Catholicism led worried members of Parliament to seek contact with his daughter Mary and son-in-law William of Orange, Stadholder of the Dutch Republic. In 1689, William invaded England and forced James to flee. Conventions in both England and Scotland declared that James had abdicated, and declared William and Mary joint monarchs. The Bill of Rights limited the power of the monarchy even more, and began to assert the concept of Parliamentary Sovereignty. It was the beginning of Constitutional Monarchy, and had been accomplished with a palpable lack of bloodshed. Hence, it would be known as the Glorious Revolution.

William arriving in England to launch the Glorious Revolution

English expansion in the Americas had begun with Virginia, spread to New England in 1621 and St. Kitts in 1623. As the century progressed, the English ejected the Spanish from Jamaica and the Dutch from New Netherlands (which became New York), so that by the end of the century the English colonial empire consisted of much of the Atlantic Seaboard in North America, much of the West Indies, and Rupert's Land, an area around Hudson's Bay claimed for the purpose of the Fur Trade. Settlement to the colonies on the mainland was extensive, and many colonies were founded for the purpose of religious freedom for certain groups, such as the Puritans in New England and the Quakers in Pennsylvania. The more Southern colonies, as well as those in the West Indies, produced tobacco and sugarcane, and relied, sadly, on slave labour. With the decline of Spain, England's main rival once again became France, and the country would go on to participate in the War of Austrian Succession.

Great Britain[]

In 1707, the Parliaments of England and Scotland both passed the Act of Union, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain. The new nation was governed by one Parliament located in London, with autonomy for various local institutions. At the time, the Union was highly unpopular in Scotland, but as time wore on a common British identity would be created, which would later extend far beyond the Island itself.

When the childless Queen Anne died, the Act of Settlement's provision for a Protestant succession bypassed the son of James II, James Stuart, and the throne fell to the Elector George of Hannover. A brief Jacobite rebellion in Scotland was crushed, and George settled in comfortably enough. Unable to speak English well and lacking an interest in British affairs, George left much of the government in the hands of the capable minister Robert Walpole. This allowed for the further development of constitutional rule, and also created a powerful new position that would evolve into that of Prime Minister. Under George II, these developments only continued.

William Pitt the Elder, Prime Minister during the Seven Years War

The Seven Years War brought William Pitt to power, and under his inspired leadership the British Empire expanded to new heights. The French defeat on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 led to the French cession of Canada, while Robert Clive was able to greatly expand the holdings of the British East India company at the expense of their French competitors. But all this glory came at a cost, and when the War was over, the burden of taxation fell on the American colonies, as it was thought that they had gained the most while expending the least effort. This misguided policy, supported by King George III (who was born and raised in Britain, the first truly British Monarch of the House of Hannover) and much of Parliament, led to disastrous repercussions in America. Protests throughout much of the late 1760s and early 1770s culminated in 1775, when the Battles of Lexington and Concord provoked an uprising throughout New England, and in 1776, when the Thirteen Colonies declared their Independence as the United States of America. The Revolution resulted in a shocking defeat for the British, and in 1783 much of the Empire in North America was gone, now an independent nation. Many Americans loyal to Britain fled to the remaining North American colonies of Canada and Nova Scotia, becoming the United Empire Loyalists.

From this humiliation, George decided to renounce his attempts at assertive royal rule, and power fell into the hands of William Pitt the Younger. Under his leadership, Britain reasserted itself as a great power, especially in the wake of the French Revolution. As France descended into anarchy and led wars of conquest in Europe to establish puppet republics, Britain opposed the French decisively. This opposition to French expansionism would continue well into the next century.

United Kingdom and the Second British Empire[]

In 1801, Great Britain and Ireland united to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. While this union occurred, Britain was in a brief lull of hostilities with Napoleonic France. By in 1803, the War would flare up again, and in 1805, Napoléon made plans for an invasion of the United Kingdom. These schemes, however, would all come to naught in July, when the British fleet under Nelson overwhelmingly defeated the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar, confirming British mastery of the seas.

The Battle of Trafalgar

The British were thus able to ward off invasion, and remained at War with France for the entirety of the conflict. Napoléon's invasion of Portugal was countered by the British Army, and the Royal Navy spirited the royal family to Brazil; when Napoléon betrayed his allies and attempted to install his brother as King of Spain, the British under Wellington gave aid to the rebels. The defeat of the Grand Armée in Russia paved the way for the formation of the Sixth Coalition, and Napoléon was eventually defeated. As the premier anti-Napoleonic power, the British were very influential at the Congress of Vienna, and when Napoléon escaped from Elba and attempted to regain his position, he was halted by Wellington at Waterloo and exiled to the British possession of St. Helena.

The postwar period was somewhat chaotic in Britain, but reform gradually took hold. As early as 1807, the slave trade was abolished, and in 1833 ownership of slaves was outlawed- despite being a tremendous strain on the government's finances and offering no conceivable economic advantage. The franchise was greatly expanded, and Parliamentary constituencies rationalised, by the Great Reform Act in 1832. Catholic emancipation had been achieved back in 1829, though Jewish emancipation would be delayed until 1858. A distinct two-party system between the Whigs and Tories developed.

Captain James Cook's voyages in the late 18th century had been greeted with interest by the British public, but one of the most significant consequences was the discovery of Australia. In 1788, a penal colony was established at Botany Bay, and by the end of the century the British had mapped and laid claim to the entire coastline of the continent. The Napoleonic Wars provided an excuse to appropriate French colonies, and the distribution of British and French colonies in the West Indies was finally settled. In addition, the British took the Cape and Mauritius, and negotiated with the Americans to gain ownership of the Oregon Country. This changed landscape of settler colonies, coupled with the growth of British India, gave rise to a new Empire. Where the First British Empire had been dominated by America, the Second Empire was much more widespread, and not entirely focused on settler colonialism. These trends would only continue.

Victorian Era[]

In 1837, the 19-year-old princess Alexandrina Victoria succeeded to the throne as Queen Victoria. The nation did not initially expect much her, and the early years of her reign were a time of political instability. However, she would die one of the longest-reigning and most beloved monarchs in British history. Her happy marriage to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha produced a new dynasty that holds the throne to this day, while her large family and its many dynastic marriages earned her the nickname "Grandmother of Europe".

The Victorian era was a time of economic and imperial expansion. Sir Robert Peel led the charge by repealing the corn laws, beginning the ascendency of Free Trade worldwide, while London, the north of England, and the central belt of Scotland led the world in industrialisation. London became the financial centre of Europe, and thereby the world. Culturally, it was a time when religion and morality were viewed as pillars of society. Reform movements had a great impact in the rapidly-growing middle-class. In the field of the arts, movements such as the Pre-Raphaelites with an emphasis on realism dominated. Literature saw the exceptional work of Charles Dickens and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Toward the end of the period, literature would still flourish in the works of authors as distinct as Oscar Wilde and Rudyard Kipling.

A short-lived rebellion in Canada came to nothing, and the crushing of the Indian mutiny in 1857 led to the end of the Mughal Empire and establishment of the British Raj over all India. Settler colonialism focused on Australia, where convict transportation was gradually phased out, New Zealand, where the provisions for the indigenous Māori were made by the Treaty of Waitangi, and Natal, which quickly surpassed the Cape as the main source of British migration to Africa.

Queen Victoria as a young woman

By 1848, Nova Scotia gained wide political autonomy and responsible government, a pattern that was repeated throughout the settler colonies. In 1867, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada confederated to form the Dominion of Canada; setting a precedent that would be repeated by Cascadia in 1889 and Australia in 1901. Political rights grew in the UK proper: in 1867 and 1884 the franchise was greatly expanded by new Reform Acts, and a distinct political culture began to emerge. The Conservative and Liberal parties, led by Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone respectively, dominated the landscape; but Charles Stewart Parnell's Irish Parliamentary Party rose to prominence by its demand of Home Rule for Ireland, a highly controversial issue that would split the Liberals. Labour unions became more powerful and successful, while local governments acquired greater responsibilities.

The UK led the world in the Scramble for Africa, and while not quite able to achieve its goal of British control from Cape to Cairo, it still acquired significant possessions. The New Imperialism focused on "civilising" indigenous peoples through education and Christianity. Though certainly not approved of today, the efforts were nonetheless in good faith, and changed the culture of Africa significantly. Missionary efforts led to the development of a ubiquitous African Christianity, and British influence can still be discerned in all independent states of the former Empire.

Throughout the Victorian Era, the British Empire stood in "Splendid Isolation" from continental Europe, and was generally unconcerned with events outside its sphere of influence. As tensions grew throughout Europe, however, the UK inevitably began to seek alliances.

Edwardian Era and Imperial Federation[]

In 1901, Queen Victoria died, provoking almost universal mourning. She was succeeded by her son, Edward VII, the first monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. A new era had dawned in British politics.

The Edwardian era was a time of extreme affluence, especially among the aristocracy, and the British upper class lived lives of incredible luxury. At the same time, prosperity was expanding in all sectors of society, and the increased representation of the working class led to greater political change. It was an era of progressivism, and the large Liberal majority elected to Parliament in 1905 were certainly in favour of this. The

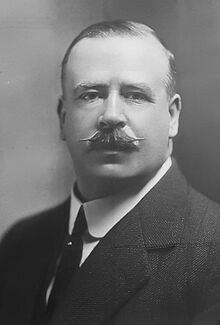

Without Joseph Ward, Imperial Federation may have been impossible

Liberal government of H. H. Asquith introduced heavier taxation on the rich, curbed the power of the House of Lords, and laid the foundations of the modern Welfare State. In Australia, the Labor Party became the first of its kind in the world to lead a government. Abroad, the UK became more involved in international affairs, and reached Verständnis with Germany.

All this occurred at a time of great Imperial loyalty, and many called for an Imperial Federation- the union of the UK and its Dominions into one pluricontinental nation. In 1911, an Imperial Conference was convened in London, and Prime Minister Joseph Ward of New Zealand called for the implementation of the Federation at the earliest possible date. Asquith demurred, believing that such a union would be detrimental to British sovereignty, but many of the other delegates were favourable, and eventually a compromise was reached: the parliaments of the UK and the Dominions would vote on weather to send delegates to an Imperial Convention. As the year progressed, all of the Dominions voted in favour, and in 1912 the Imperial Convention met in London. In a little over a month, the Convention had drafted a constitutional document, the Constitution of the Imperial Federation Act. This provided for a Parliament in London with authority over defence, trade, foreign affairs, and the remaining colonial Empire, while providing autonomy for the realms (Great Britain and Ireland) and Dominions. By 17 October all of the Parliaments had ratified the Act, and the Imperial Federation of the British Empire was formed.

New Nation in a Changing World[]

While the UK and Germany were able to avoid entry into the Great War, they still suffered from the ripple effects of scarcity and the Great Flu. Regardless, the UK remained more or less as strong as it had been due to not participating in the War, and as another consequence the country retained a sense of optimism. Women were granted the right to vote, and property qualifications were gradually abolished. The UK continued to set a pattern for advanced legislation.

Unemployed workers durning the Great Depression

In the wake of the Great War and Great Flu, a tremendous economic boom rocked the world in the 1920s, and the UK was one of the greatest beneficiaries. But in 1929, the American Stock Market crashed, and a ripple effect of tariffs and protectionism let to the Great Depression. The Depression had as much of a negative impact on the UK as on any other country, but the most worrying consequence was abroad, where Syndicalism was on the rise in Europe.

Disturbed by the rapid spread of Syndicalism, and the strong organisation of the Syndicalist powers, the UK brought together other liberal democracies in Northern Europe to form the North Sea Treaty Organisation, an alliance for mutual defence. This led to the Cold War, a time of escalating tensions between the Syndicalist and Democratic countries.

The Cold War and Beyond[]

Initially, the Cold War was pursued with almost single-minded devotion. But in the 1960s, cracks in the system began to show. A right-wing youth culture challenged the liberal consensus, and many mainstream politicians began to seriously question the seriousness of the conflict. Even on the left, many decried the Cold War as an imperialist conflict. This disunity at home was compounded by decolonisation, which had started with India in 1947, been accelerated with Ghana ten years later, and resulted in the almost wholesale abandonment of the Colonial Empire. At the same time, however, the UK expanded. The West Indies Federation was admitted to the Imperial Federation in 1960, which produced a small but significant trend of former colonies joining the UK, such as Mauritius and Fiji. The fact that all of the new Dominions were majority non-white accelerated the push toward full racial equality. Indigenous rights movements began to gain prominence in South Africa, Australia, Canada, Cascadia, and New Zealand.

Margaret Thatcher, whose government was generally credited with winning the Cold War

The new distrust of the Cold War led Prime Minister Edward Heath to began a policy of dialogue with the Pact of Steel. This new model assumed that the divisions between Syndicalism and Democracy were entrenched, more or less permanent, and that the Cold War was unwinnable. This became an orthodoxy at the Foreign Office, and was continued throughout the 1970s. This was changed by Margaret Thatcher's victory in the 1979 elections.

Thatcher, believing that the Cold War was winnable, began an arms race with the Pact of Steel. This aggressive foreign policy led to similar countermeasures within the Syndicalist bloc, and Argentina almost provoked a global war with the South Georgia crisis of 1982. Eventually, however, the less-advanced Syndicalist economies came under heavy strain, and reform movements gained greater force. Gianfranco Fini's rise to become Prime Minister of Italy signified change, and his pro-market and pro-democratisation reforms were widely copied by other Syndicalist powers. Fini even began negotiations with Thatcher, but her government was unwilling to give up on any of its policies, and thus the arms race continued. But a combination of the strain put on the Syndicalist military-industrial complex, combined with the spiraling consequences of reform, led to the Revolutions of 1990, which toppled Syndicalism worldwide. Thatcher resigned, stating that she had gone into federal politics in the first place due to the Cold War, "and now my work is done".

Geography[]

The total land area of the UK is approximately 8,442,756 square miles, which makes it the largest sovereign state in the world by area. The UK is so large due to its pluricontinental nature, and it encompasses incorporated territory on five continents. In Europe, the UK holds the British Isles in their entirety, as well as the small peninsula of Gibraltar on the coast of Spain. In Africa, the UK controls significant territory on the far southern tip of the continent, as well as the archipelago of the Seychelles and the island of Mauritius. The UK includes all of the Australian continent, the islands of New Zealand, the islands of Fiji, and several island chains and archipelagoes in Micronesia and Polynesia. South American territory is limited to Guyana, but the UK also controls much of the West Indies, and the northern half of the North American continent.

Political Divisions[]

Map of the UK, including colonies, and showing borders between Dominions

The UK is divided into a total of fourteen Realms and Dominions (about the governance of which, see below). These are each considered sovereign states within the greater sovereign state of the UK, and many of them are themselves federations.

The following list of Realms and Dominions (collectively referred to as Constituent States) is provided for reference:

| Flag | Constituent State | Capital | Largest City | Population | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Canberra | Sydney | 25,053,021 | 2,969,907 sq mi | |

| Canada | Ottawa | Toronto | 34,632,012 | 3,698,450 sq mi | |

| Cascadia | Portland | Seattle | 8,504,443 | ||

| Fiji | Suva | Suva | 884,887 | 7,056 sq mi | |

| Gibraltar | Gibraltar | Gibraltar | 32,194 | 2.6 sq mi | |

| Great Britain | London | London | 61,389,512 | 80,823 sq mi | |

| Ireland | Dublin | Dublin | 6,572,728 | 32,595 sq mi | |

| Kiribati and Tuvalu | Tarawa | Tarawa | 112,617 | 323 sq mi | |

| Mauritius | Port Louis | Port Louis | 1,233,000 | 790 sq mi | |

| Newfoundland | St. John's | St. John's | 519,716 | 156,650 sq mi | |

| New Zealand | Wellington | Auckland | 4,242,048 | 103,483 sq mi | |

| Seychelles | Victoria | Victoria | 94,228 | 177 sq mi | |

| Union of South Africa | Cape Town; Pietermaritzburg | Cape Town | 22,491,777 | ||

| West Indies | Kingston | Kingston | 8,107,728 | 105,118.5 sq mi |

Environment[]

Due to its pluricontinental nature, the environment of the UK is very diverse.

The Glendlough Valley in Ireland

The British Isles vary in elevation, ranging from flat, sea-level lands to high mountain ranges. Much of the land is used for agricultural purposes. In Ireland and much of England, the remaining lands are primarily forest, while in the north of England and much of Scotland the natural landscape is dominated by moorland. The highest peak in the region is Ben Nevis, in Scotland, which reaches 4,413 ft. Gibraltar is dominated by the 1,398 ft high Rock of Gibraltar, and has negligible natural resources.

Table Mountain near Cape Town on a cloudy day

In the Union of South Africa, much of the interior is characterised by high plateau and savannah, with deserts predominating in the far north. South of this, the plateau drops off into mountain ranges, with the Cape Fold mountains in the west and the Drakensburg in the east. Below the mountains is a fertile coastal belt, which tends to be a mixture of savannah and forest. Offshore, the Union is located in a particularly mineral-rich marine area, which leads to an abundance of marine life. The highest point, at 11,320 ft, is Mafadi, in Natal.

Mauritius and the Seychelles are both dominated by tropical forest and agricultural land, and have a thriving marine environment. The highest point on any of the Indian Ocean islands is Piton de la Petite Rivière Noire, in Mauritius, at 2,717 ft.

Uluru, or Ayers Rock, a landmark of the Australian Outback

Australia is also quite varied, and much of the interior, the Australian Outback, is dominated by desert. In the far north of the country, tropical savannahs predominate, mixed with a fair amount of rainforest. Aside from more mild regions on the southwestern and south-central coasts, the main fertile region is found on the east coast, where most Australians live. This is separated from the desert by a large mountain range, the Great Dividing Range. Temperate grassland, the heart of Australia's agricultural economy, predominates, with a good deal of forest and bush mixed in. Tasmania is dominated by temperate forests. Australia has a flourishing marine environment, and is especially noted for the Great Barrier Reef off Queensland. The highest mountain on the continent is Mt. Kosciuszko, at 7,310 ft, in New South Wales.

Milford Sound in New Zealand, once described by Rudyard Kipling as the eighth wonder of the world

New Zealand is much cooler, and though much of the land is now used for agricultural purposes, a significant portion of the original temperate rainforest remains. Much of the South Island is quite mountainous, while North Island is flatter. New Zealand is equally rich in natural beauty offshore, where kelp forests and some of the most advanced environmental laws in the world contribute to a rich, thriving ecosystem. New Zealand's highest point is Aoraki (Mt. Cook), at 12,218 ft.

Kiribati and Tuvalu consist of low-lying coral atolls, with the undersea environment having greater ecological significance.

Fiji is mostly mountainous, and dominated by tropical forest. Its marine environment is characterised by extensive coral reefs. The highest point is Mt. Tomanivi, at 4,344 ft.

Gros Piton in Saint Lucia

The West Indies encompasses many mountainous tropical islands of the Caribbean, several more low-lying Atlantic islands, and enclaves on continental North and South America (namely Belize and Guyana, respectively). As such, while much of the country is dominated by tropical forest, and can sustain intensive agriculture, certain islands are more arid. The country is part of the ecologically rich Caribbean region, and is noted for its many reefs. On land, the highest point is, at 6,696 ft, Mt. Ayanganna in Guyana.

The Oregon Coast

In North America, the UK contains very diverse land. The far north is an Arctic region, dominated by glaciers and tundra. South of this, a subarctic belt of dense boreal forest predominates from coast to coast. The Atlantic coast is much more temperate, with rocky, hilly terrain and extensive deciduous forests. In the St. Lawrence River Valley, these forests continue to hold sway, but the ground becomes slightly more fertile. Past this is the Canadian Shield, which separates this climate from the more subarctic boreal forests, while to the south lie the Great Lakes. To the west, the Prairie Provinces of Canada are the region's agricultural heartland, with much of the land being taken up by farms. The natural environment is grassland. The continent is divided in half by the Rocky Mountains and the Alaska range, which are noted for their great height and majestic scenery. To the west, the land is again varied. Mountains continue to dominate in much of the British Columbia interior, while to the south the area between the Rockies and the Cascade mountains is a flat, arid region that has been transformed into an agricultural centre through irrigation. West of the Cascades and the Coast Ranges, the land is dominated by wet temperate rainforests. British North America's marine environment is also diverse. The Arctic waters are still rich in life, while the Atlantic is especially so, though its fisheries have been much reduced in the recent past. The Pacific is also home to much biodiversity, and contains many kelp forests. The highest point, Denali, reaches 20,237 ft; making it simultaneously the highest mountain in Alaska, Cascadia, the UK, and North America.

Climate[]

As with the environment, the UK's climate varies greatly. The British Isles have an Oceanic climate characterised by cool summers and mild winters. Gibraltar has a Mediterranean climate, as does much of the region around the Cape of Good Hope proper. Otherwise, the climate of the Union of South Africa is quite variable, and includes deserts with little rainfall in the north, a mild Oceanic climate along the Garden Route, and a Subtropical Grassland climate in much of Natal. Mauritius and the Seychelles have a wet, Tropical climate. Australia is quite variable as well, with Hot Desert climates dominating much of the Outback, but the coastal regions include Tropical Savannah and Tropical Monsoon climates in the north, Mediterranean climates around Perth and Adelaide, and Oceanic climates in much of the southeast coast. New Zealand's climate is almost purely Oceanic. Both Fiji and Kiribati and Tuvalu have Tropical climates, as does the West Indies. British North America encompasses Arctic and Subarctic climates in the north, while temperate Continental climates typified by hot to warm summers and cold winters are found throughout much of the Atlantic region, Central Canada, and the Prairie Provinces. West of the Rockies, the climate varies due to mountains and rainshadow, but much of the coast has an Oceanic climate.

Dependencies[]

The United Kingdom retains eight Crown Colonies, relics of the former colonial Empire. They are:

| Flag | Crown Colony | Capital | Largest City | Population | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascension Island | Georgetown | Georgetown | 806 | 34 sq mi | |

| British Antarctic Territory | n/a | n/a | 0 | 3,106,700 sq mi | |

| Falkland Islands | Stanley | Stanley | 2,955 | 4,700 sq mi | |

| Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 7,448,900 | 428 sq mi | |

| Pitcairn Islands | Adamstown | Adamstown | 49 | 18 sq mi | |

| Saint Helena | Jamestown | Half Tree Hollow | 4,534 | 47 sq mi | |

| South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands | n/a | n/a | 0 | 1,570 sq mi | |

| Tristan da Cunha | Edinburgh of the Seven Seas | Edinburgh of the Seven Seas | 300 | 80 sq mi |

The number of Crown Colonies heavily declined in the mid-20th century, mostly due to independence movements. However, many of the larger ones were also absorbed into the Imperial Federation as Dominions, while other areas of smaller population were granted to the Dominions as dependencies. There has long been a push to make Hong Kong a Dominion, but this has been put off for fear of antagonising China. The admission of Gibraltar as a Dominion set a precedent, however, and the current government has pledged to begin the process of admitting Hong Kong.

In addition to this, the Kingdom of Great Britain has three self-governing Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Guernsey, the Bailiwick of Jersey, and the Isle of Man. These are not considered to be formally part of Great Britain, though they are integral territory of the UK nonetheless.

Politics and Government[]

Elizabeth II, Queen of the UK

The government of the UK takes the framework of a Confederal Constitutional Monarchy.

The Crown and Executive Power[]

The Queen is head of state, and nominally charged with extensive powers. As a matter of fact, however, royal power is extremely limited, and the monarch's position is mostly ceremonial. In the words of 19th-century constitutional scholar Walter Bagehot, it represents the "dignified element" of the constitution, and has "the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn". The powers of the monarchy, called reserve powers, are mostly gone into abeyance, and the Crown largely serves as a symbol of national unity.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Executive power is in fact centred in the Prime Minister and cabinet. Formed by the leadership of the largest political party in Parliament, the cabinet is responsible for introducing key legislation, administering executive agencies, and the overall direction of the government. The Prime Minister leads and coordinates the cabinet in these efforts. As such, s/he is the effective leader of the country. Nominally, the cabinet advise the Crown through the Privy Council.

Parliament[]

The legislative body of the UK at the Imperial level is the Parliament, a bicameral body which operates from Westminster in London. Parliament is sovereign over all areas delegated to the Imperial government, and is the basis of government.

The Palace of Westminster, seat of Parliament

Officially, Parliament consists of the Queen, the House of Delegates, and the House of Representatives. The term Queen-in-Parliament represents that the monarch is officially the legislator, and acts only with the advice and consent of Parliament. The House of Delegates is the upper house of Parliament, with a largely ceremonial role, and consists of delegates appointed for life by the governments of their Constituent States, of which there are three for each.

Given the lack of power in the other two components of Parliament, the House of Representatives is consequently the most important part of Parliament. All governments are based in the House of Representatives, and all legislation issues from the lower house.

Politically, the largest party (or coalition) in the House of Representatives forms Her Majesty's Government, and controls the cabinet and Premiership. The second-largest party (or coalition) forms Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition, which critiques the government, offers alternatives to government policy, and forms a shadow cabinet which will take over should the party win election. Other parties and coalitions are without official status, though they continue to exert authority over their members and form their own shadow cabinets.

Elections to Parliament take place at least every five years, though the Prime Minister can ask the monarch to dissolve Parliament at any time, meaning that elections take place much more frequently. The method of election to the House of Delegates varies by Constituent State, as the Imperial Parliament has no authority to regulate elections.

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council[]

Room used by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council serves as the court of last resort, and has authority over all matters of constitutional law. Its authority applies chiefly to Imperial matters, though the governments of the Realms and Dominions may refer cases to it, in which case the ruling is final and cannot be overruled. For this reason, referrals are no longer common, and have been officially abolished by many Constituent States.

The Committee is formed by a Board of five judges, whose report on a case is accepted by the Queen as a judgment. In Imperial matters, the judgements of the Committee serve much as in any high court, and may be overruled.

Imperial Government and Constituent States[]

As a confederation, the Imperial government is regulated to only a few powers, namely foreign affairs, defence, trade, and the colonies. However, the Imperial government is sovereign in these areas, and as the Imperial Federation is considered indissoluble it is impossible for a Constituent State to leave. This makes the UK one of the most centralised operative confederations in history.

The Constituent States are divided into Realms and Dominions, the distinctions between which are largely academic. Both have equal power over their own affairs; the only real differences are that Realms are entitled to be called Kingdoms, have a Lord Lieutenant as opposed to a Governor-General, and rank first in the order of precedence.

Government of the Constituent States is generally on the same model as the Imperial Government, with a strong Parliament, a government formed by the majority party, ceremonial monarchy (represented by the Governor-General or Lord Lieutenant), and an aloof judicial branch. The main difference is constitutionalism, as many (though not all) have written constitutions.

Constitution[]

The Constitution of the UK is largely unwritten, meaning that much of it is based on custom and precedent. However, certain written documents help to codify British constitutional law, including:

- Magna Carta 1215: certain statues remain in effect, including the right of due process

- Petition of Right 1628: restricts arbitrary authority of the monarch

- Habeas Corpus Act 1679: provides against arbitrary imprisonment

- Bill of Rights 1689: provides for certain individual rights and Parliamentary powers

- Act of Settlement 1701: codifies succession to the throne

- Imperial Federation Act 1912: provides for the Imperial government

Collectively, these form the basis of constitutional law in the UK.

Law and Criminal Justice[]

On the whole, the UK is a Common Law jurisdiction. However, at various local levels Common Law is mixed with Civil Law (as in Scotland, Québec, and the Union of South Africa), owing to historical reasons.

Criminal statistics are not collected at the Imperial level, especially given that the Imperial government has little authority to define and punish crimes. However, criminal acts relating to foreign and interstate trade are tried in Imperial courts, which are organised into districts by Constituent State and federal divisions within them. Additionally, Imperial courts have the authority to try British Subjects for treason.

Political Parties[]

As a pluricontinental nation, it is understandably hard to form real links between the various local parties existing in the Constituent States. Nevertheless, a three-party system has developed at the Imperial level between the centre-right Federalists, the centrist Liberals, and the centre-left Social Democrats. In addition to these, the Coalition for Indigenous Rights has been influential since the 1970s, though a combination of low indigenous populations and support for other parties has effectively limited it to the Union of South Africa.

Foreign Affairs and Defence[]

Foreign Relations[]

The UK is a member of the North Sea Treaty Organisation, the Commonwealth of Nations, the G7, and the G20.

In terms of bilateral alliances, the UK is said to have a "Special Relationship" with the US, meaning that of all foreign nations, the isolationist US is closest to the UK. The UK has had a longstanding alliance with Belgium since that country's independence. Since Verständnis with Germany in 1904, the two countries have also been closely linked. The Anglo-Portuguese alliance, though frayed by the Cold War, has since developed fruitfully and remains the oldest military alliance in the World.

Military[]

The HMS Richmond at sea

The Armed Forces of the UK are divided into three branches- the Royal Navy (and Royal Marines), the British Army, and the Royal Air Force.

Militarily the most important power in the world, the UK continues to depend largely on the Royal Navy. Preference for naval power is due to a combination of several reasons, including the fact that the British Isles are islands, Whig dislike of standing armies, and a heroic naval tradition. Whatever the rationale, the UK's naval supremacy is palpable worldwide, and the nation maintains active fleets in all four oceans.

Globally, the UK participates in the North Sea Treaty Organisation and has various bilateral alliances with other nations.

Economy[]

The UK has a highly developed free-market economy. It is the largest economy in the world by nominal GDP. As of 2019, it was the second-largest exporter of goods in the world, and the third-largest importer.

A highly globalised economy, the UK is nevertheless fully self-sufficient in resources, particularly lumber, foodstuffs, and fuel. As a developed country, the service sector is the most important, comprising about 61% of those employed in the UK. However, the natural resources economy is considered the backbone of the nation, and comprises 45% of the total GDP. Industry and Agriculture employ 29% and 10% respectively.

London, centre of the British Economy

Within the service sector, financial services are particularly important, especially in London, the world's largest and most important financial centre, and includes such prominent corporations as Lloyd's. Tourism is also important, as the UK receives the most tourism of any nation on earth. The creative industry is also important.

In terms of manufacturing, the UK has led the world since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The aerospace industry is particularly important, with such corporations as Boeing and Bombardier being based in the UK. The automotive industry lags behind that of Japan and the US, but is still substantial, especially in the realm of luxury cars such as Jaguar and Rolls-Royce. Technology is also important, especially in Cascadia, where Microsoft is based.

The natural resources economy is very diverse, on account of the Imperial Federation's pluricontinental territory. Agriculture is mainly concentrated in Canada, where the Prairie Provinces are leaders in wheat production, while the West Indies remains the nation's main source of tropical fruit and spices. Australia and New Zealand are both important for their vast herds of sheep and cattle, and produce wool, meat, and dairy products. Cascadia and western Canada are important for their lumber industry, while much of the UK is blessed with fertile fishing grounds.

The UK is also a leader in the global production of fuel. Switchgrass ethanol is particularly important in Canada and the Union of South Africa, while sugarcane ethanol is important to the economies of the West Indies and Mauritius.

Demographics[]

According to the most recent census of the United Kingdom, the total population in 2016 was 173,869,911. This makes the UK the seventh-largest nation in the world by population. The growth rate was approximately 0.5%, of which approximately 59% is due to births and the other 41% due to immigration. The UK is very receptive to immigration, particularly from the Commonwealth, and as many as 10% of all UK residents are foreign-born.

Total fertility in the UK is relatively low, but boosted by higher rates in the West Indies and the Union of South Africa, so that the overall output is slightly above replacement rate. The average life expectancy is 80 years (76 for males and 85 for females), and the median age is 41.7.

Urbanisation[]

The UK is a relatively urbanised country, and cities of considerable size are dispersed throughout the country.

| Ranking | Metropolitan Area | Population | Constituent State | Subdivision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | London | 9,787,426 | Great Britain | England |

| 2nd | Toronto | 6,417,516 | Canada | Ontario |

| 3rd | Sydney | 5,230,330 | Australia | New South Wales |

| 4th | Melbourne | 4,932,000 | Australia | Victoria |

| 5th | Cape Town | 3,740,026 | Union of South Africa | Cape of Good Hope |

| 6th | Durban | 2,839,425 | Union of South Africa | Natal |

| 7th | Seattle | 2,093,112 | Cascadia | Wellington |

| 8th | Montréal | 1,942,044 | Canada | Québec |

| 9th | Auckland | 1,695,900 | New Zealand | n/a |

| 10th | Calgary | 1,392,609 | Canada | Alberta |

Ethnic Groups[]

The UK is a diverse, multicultural nation, with several major ethnic groups scattered across the country.

New Zealanders at an Anzac Day service

The majority of British Subjects are "White", a broad category referring to European ancestry. Of these, those of Anglo-Celtic background are most prominent. Descended from the peoples of the British Isles, and thus having varying degrees of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman ancestry, Anglo-Celtic peoples are divided into four distinct groups: the English, Scots, Irish, and Welsh. Of these, the English have been historically considered a Germanic people, while the Irish and Welsh have been considered Celtic. The Scots are regarded as a mixture of the two. In addition to these four main groups, there are notable subgroups which may also be considered separate ethnicities, such as the Ulster Scots and the Cornish. Within the British Isles, ethnic identities are strong, but in the former settler colonies, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, separate identities are weaker and thus most identify with the vaguer category of Anglo-Celtic.

Other Whites are prominent in the UK. In particular, there are two significant non-Anglo-Celtic groups: the French-Canadians and the Afrikaners. French Canadians descend from the settlers of New France, which encompassed much of what is now Canada, and are especially concentrated in Québec, where they form the majority. Other notable concentrations are in New Brunswick and Manitoba. However, Francophone communities can be found throughout Canada. It is in Québec, however, that French-Canadian nationalism is strongest, and souverainistes within the Province call for a separate Dominion of Québec, or even independence (though the latter has been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council). Still, the French Canadians are recognised as a Distinct Society within Canada, and due to them Canada is officially bilingual.

Afrikaners are found in the Union of South Africa, overwhelmingly in the Cape. Descended from the settlers of the Dutch Cape Colony, which was annexed by the UK during the Napoleonic Wars, they are part of a larger Afrikaner identity which is distributed throughout Southern Africa. In fact, most Afrikaners live in the Republic of South Africa, where they form the majority of Whites; many left the Cape in the Great Trek after the British abolished slavery, which was historically practiced by the Afrikaners. Those who stayed, however, remain prominent in the Cape, particularly in the rural southwestern region around Cape Town. As such, Afrikaans is co-official with English in the Union of South Africa.

Other White groups are scattered throughout the nation, largely the descendants of immigrants. Germans are found in all the former settler colonies, but especially in western Canada and South Australia. Scandinavians may be found in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and so can those with Dutch ancestry. Italians are similarly spread out. Some groups are less widely dispersed, such as the Ukrainians who form a significant presence in the Prairie Provinces, or the Greeks is Australia (Melbourne has more Greeks than any city other than Athens).

The Prince and Princess of Wales in the West Indies Federation

The largest minority in the UK is certainly the Black community, which is divided between the Afro-Carribbean and Black African groups. Of these, Black Africans are the larger group, and are the Indigenous Peoples of the Union of South Africa. While some sense of solidarity exists, most Black South Africans concentrate on their tribal loyalties. The two largest tribes are the Zulu, who form the majority in Natal, and the Xhosa, who are found in the eastern regions of the Cape. Originally under segregation, their standing improved during the 1960s and 1970s, and while some prejudice remains, the Union of South Africa has been under Black majority rule since. However, they continue to suffer disproportionately from poverty and crime, and many emigrate to the Republic of South Africa for work, even though this means the loss of political rights and becoming stateless. The Imperial and Dominion governments have pledged to resolve the crisis, but little progress has been made.

The rest of British Blacks are overwhelmingly Afro-Carribbean, descendants of slaves brought to the West Indies in the 17th and 18th centuries. This resulted in the blurring of African identities and the birth of a new, "Black" identity that has defined the people of the region ever since. Afro-Carribbean people are mostly found in the West Indies, and from a majority in all but three States. Additionally, significant migrant communities are found in Great Britain (particularly London), and Canada (particularly Toronto).

Significant Asian minorities also exist in the UK. Asian Indians have historically constituted the majority of these, as durning the 19th century many migrated from British India to serve as indentured labourers in the wake of the abolition of slavery. As such, large Indian communities are found in areas where the plantation system once prevailed. They form the majority in Mauritius, as well as the West Indian States of Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago, and are the second-largest ethnic group in Fiji. Signifiant groups also exist in Natal. These historic communities are countered by modern immigration from the subcontinent, which is mostly among skilled professionals and occurs in urban areas. Great Britain and Canada have significant Indian minorities.

East Asians are also significant, and may soon dramatically increase if plans to make Hong Kong a Dominion succeed. The existence of a large Asian colony, coupled with the economic status of the UK, makes immigration appealing and has been so since the 19th century. Anti-Chinese sentiment has a long and unfortunate history in Canada, Cascadia, and Australia, but increased racial tolerance led to a gradual loosening of immigration laws, and hence a large Asian influx into the UK, particularly into Constituent Countries along the Pacific such as Australia, New Zealand, and Cascadia, where East Asians form the majority of immigrants, and to Canada, where they form a significant percentage. As ever, London also has a significant East Asian population.

The remaining groups are largely indigenous peoples, who unlike Blacks in the Union of South Africa have been largely eclipsed by White settlers. Of these, the First Nations and Inuit peoples are the aboriginal peoples of Canada and Cascadia, the Polynesian Māori are native to New Zealand, and the Australian Aboriginals are indigenous to that country.

There are further Oceanian groups which form the majority in their own Dominions. Gilbertese and Tuvaluans, respectively Micronesian and Polynesian ethnic groups, form the majority in Kiribati and Tuvalu. Fiji's indigenous people, and narrow majority, are the Fijians, a Melanesian group.

Other groups include Latin Americans, who form the majority in the West Indian State of Belize and a sizable majority in British North America; the Jewish population, who are distributed mostly in urban centes throughout the UK; and the Roma, who form a very small but still visible minority in the British Isles.

Languages[]

The de facto official language of the UK is English, which is understood by almost 99% of the population. At various other levels, bilingualism is mandated: French in Canada and Mauritius; Afrikaans in the Union of South Africa; Fijian and Fiji Hindi in Fiji; Māori in New Zealand; Spanish in Gibraltar; and Glibertese and Tuvaluan in Kiribati and Tuvalu. Additionally, there are many languages that are widely spoken but do not possess official status, most importantly Xhosa, Zulu, and Tswana in the Union of South Africa. In several formerly French colonies, such as Mauritius and the West Indian state of Dominica, French-based creoles serve as the lingua franca, while the West Indian State of Belize is majority Spanish-speaking due to its proximity to Mexico and Latin America. Additionally, there are several minority languages that are largely extinct, such as the indigenous languages of Australia, Canada, and Cascadia, and the Celtic languages of the British Isles such as Irish, Welsh, Cornish, and Manx.

Religion[]

The United Kingdom is a fairly religious country, but this varies by Constituent Country: while 71% of Irish consider themselves religious, that figure drops to 54% in neighbouring Great Britain, and even here this varies considerably from 69% in Scotland to 21% in the City of London.

Canterbury Cathedral, seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury

The overwhelming majority of British Subjects are Christians, mainly Anglicans, Roman Catholics, Presbyterians, and Methodists. Of these four, three originated in the British Isles. Anglicanism is the global extension of the theology of the Church of England, and as such all Anglicans worldwide recognise the primacy of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Presbyterianism developed as a form of Calvinism distinct from the Continental variety in Scotland, while Methodism originated in the Great Awakening and the theology of John and Charles Wesley. Other Christian groups with prominence in the UK include the Reformed, Lutherans, African Independent Churches, Congregationalists, Baptists, and Eastern Orthodox.

Among non-Christian religious groups, Hindus are the most prominent, forming the majority in Mauritius, and the second-largest group in Fiji and the West Indian States of Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago. Areas with large Indian Communities also have a notable Islamic presence. Judaism is found in Jewish communities throughout the nation. Indigenous religions are a small, but notable, minority in Cascadia, Canada, Australia, and the Union of South Africa.

Culture[]

Due to the pluricontinental status of the UK, it is somewhat difficult to define a common British culture. Nevertheless, one definitely exists, and has since the late 19th century. British subjects are united by a sense of patriotic reverence for the Imperial Federation, loyalty to the same Monarch, and similar systems of law and government, but also by several common cultural traits, generally originating in the British Isles.

Literature[]

William Shakespeare, the "national bard"

British literature originated in the Middle English literature that developed in the late Middle Ages. The country is known for its proud history in the realm, and is the largest publisher of books in the world.

Notable Mediaeval and Early Modern authors include Geoffrey Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales); Thomas Malroy (Le Mort d'Arthur); Sir Thomas Moore (Utopia); and Christopher Marlowe (Tamburlaine, Doctor Faustus). The late Elizabethan and early Jacobean eras were marked by the rise of William Shakespeare, considered the "national bard" of England, and often referred to as the greatest writer in the world. His plays include Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Henry IV, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, Twelfth Night, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, and The Tempest.

17th century literature was often more religious, such as the works of John Bunyan (Pilgrim's Progress) and the great poet John Milton (Paradise Lost). The 18th century produced Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe), Samuel Johnson, the great man of letters, the Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift (Gulliver's Travels, A Modest Proposal), and the poet Alexander Pope (The Rape of the Lock, Dunciad). Later in the century, the great poet Robert Burns would publish a wide body of work in Scots (such as Auld Lang Syne, Scots Wha Hae, A Red, Red Rose, A Man's a Man for A' That, To a Louse, To a Mouse, The Battle of Sherramuir, Tam o' Shanter, Ae Fond Kiss).

Charles Dickens, the great Victorian novelist

The 19th century would see some of the greatest works of British literature. The Regency period saw the works of Jane Austen (Pride and Prejudice, Emma), the Romantic poetry of Lord Byron (Don Juan, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage), Percy Bysshe Shelly (Ozymadias, Prometheus Unbound), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan), and William Wordsworth (The Prelude); as well as the Gothic literature of Mary Shelly (Frankenstein). It was the Victorian era, however, that provided the most lasting works. The most prolific author of the period was Charles Dickens (The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, David Copperfield, Bleak House, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations). Other notable novelists included Charlotte Brontë (Jane Eyre) and William Makepeace Thackeray (Vanity Fair); the most prolific Victorian poet was Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Mariana, The Charge of the Light Brigade). Later, the period saw social critics like Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Grey, The Importance of Being Ernest), Imperialists like Rudyard Kipling (If, Gunga Din), and the multifaceted work of Robert Louis Stevenson (Kiddnapped, Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde).