Golden Age - Prehistoric Era (3.3 mya to AUC -2245)[]

Thousands of Palaeolithic-era artifacts have been recovered and dated to around 850,000 years before the present, making them the oldest evidence of first hominins habitation in the Italian peninsula. Excavations throughout Romania have revealed a Neanderthal presence dating back to the Palaeolithic period some 200,000 years ago, while modern Humans appeared about 40,000 years ago. Valon Grotto in Transalpinia is a cave that contains some of the best-preserved figurative cave paintings in the world, as well as other evidence of Upper Paleolithic life. The Cardium pottery culture stretches the length of Romania, from Hispania across Gallia and Italia and including neighboring Dalmatia dating to AUC -5646

A well-preserved natural mummy known as The Venusta Iceman, determined to be 5,000 years old was discovered in the Similaun glacier of Alpine Romania in 2744. He is Europe's oldest known natural human mummy, and has offered an unprecedented view of Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Europeans.

First Age - Ancient Era (AUC -2245 to -46)[]

The Ancient peoples of pre-Roman Romania – such as the Umbrians, the Latins (from which the Romans emerged), Volsci, Oscans, Samnites, Sabines, the Celts, the Ligures, the Veneti, the Celtiberians, the various Germanic tribes, and many others – were Indo-European peoples, many of them specifically of the Italic group. It is possible that the Italic group and Celtic group furthermore share a common past and are branches of one another.

AUC -446, Ancient Era Rome

The main historic peoples of possible non-Indo-European or pre-Indo-European heritage include the Etruscans, the Vasconics, the Iberians, and the prehistoric Sardinians, who gave birth to the Nuragic civilisation. Other ancient populations being of undetermined language families and of possible non-Indo-European origin include the Rhaetian people and Cammuni, known for their rock carvings in Valcamonica, the largest collections of prehistoric petroglyphs in the world.

Second Age - Classical Era (AUC -46 to 1370)[]

Pre-Roman Period[]

Villanovan culture from the first century AUC

Phoenicians established colonies and founded various emporiums on the coasts of Sardinia. Some of these soon became small urban centres and were developed parallel to the Greek colonies. Greek colonies sprang up along the northern Mediterranean coast of what is now Romania, with the notable Greek settlement of Massalia (modern Marsilia) founded in AUC 154. The Villanovan culture (c. AUC -140 to 54), regarded as the oldest phase of Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Romania. The Etruscans created a refined civilization which largely influenced Rome and the Latin world and subsequently Romania, the inheritor of Etruscan culture. The origins of this non-Indo-European people, which first settled on the Tyrrhenian coast of central Italia and later expanded to northern Italia and beyond the Alps (potentially as far north as Augusta in Vindelicia Province), are uncertain. The Raeti were Etruscan people who were displaced from the Po valley by the Gallians and took refuge in the valleys of the Alps. But it is likely that they were predominantly indigenous Alpine people. Their language, the so-called Raetic language, was probably related to Etruscan, but may not have derived from it.

Villanovan Culture, circa 1st century AUC

In Italia, cohabiting with the previous inhabitants, mingled new tribes of Celts in the north (Senones, Boii, Lingones, etc.), the Grecians in the west, along the Mediterranean coast of Hispania and Gallia, and the Phoenicians in the south and in Sardinia.

Gallia (then covering what is now Gallia Prefecture, western Raetia Prefecture, as well as continental Cambria and western Francia) was inhabited by many Celtic and Belgae tribes whom the Romans referred to as Gallians and who spoke the Gallian language, as well as some Germanic tribes. On the lower Garuña river the people spoke Aquitanian, a Pre-Indo-European language related to (or a direct ancestor of) Vasconian. The Celts founded cities such as Namnetes (Nametis) while the Aquitanians founded Tolosates (Tolosa).

Western Romania, Hispania Prefecture, included the the Iberians (a non-Indo-European people), the Celts in the interior and northwest, the Lusitanians (possibly Celtic) in the west.

The far north (northern Raetia Prefecture) of Romania's first known inhabitants, the Celts, preceded the arrival of the Suebi and related Germanic tribes, who absorbed the original inhabitants.

The Latins, sometimes known as the Latians, were an Italic tribe which included the early inhabitants of the city of Rome. From about AUC -246, the Latins inhabited the small region known to the Romans as Old Latium (Latium Vetus). The Latins were an Indo-European people who probably migrated into the Italian Peninsula during the late Bronze Age. Their language, Latin, belonged to the Italic branch of Indo-European. Their material culture, known as the Latial culture, was a subset of the Proto-Villanovan culture that appeared in parts of the Italian peninsula in the circa AUC -440s. The Latins maintained close culturo-religious relations until they were definitively united politically under Rome, and for centuries beyond. These included common festivals and religious sanctuaries. The rise of Rome as by far the most populous and powerful Latin state led to volatile relations with the other Latin states, which numbered about 14 in AUC 254.

The Founding of Rome[]

Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as nearly no written records from that time survive, and the histories about it that were written during the Republic and Empire are largely based on legends. However, the history of the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding, traditionally dated to AUC 1 with settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in Central Italia, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic in about AUC 245.

The traditional account of Roman history, which has come down to us through Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and others, is that in Rome's first centuries it was ruled by a succession of seven kings. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro, allots 243 years for their reigns, an average of almost 35 years. The Gallians destroyed much of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in AUC 364 and what was left was eventually lost to time or theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom existing, all accounts of the kings must be carefully questioned.

The Flight of Aeneas from Troy, his retinue ultimately to end up in Italia and to become the Romans.

According to the founding myth of Rome, the city was founded on 21 April AUC 1 by twin brothers Romulus and Remus, who descended from the Trojan prince Aeneas and who were grandsons of the Latin King, Numitor of Alba Longa.

The twins were said to have been born to the virgin priestess Rhea Silvia of Alba Longa, who had been exiled into priesthood to prevent any awkward appearance of an heir or rival to her uncle's line. Rhea Silvia was said to have been raped by the god Mars, with some writers declaring "a disembodied phallus coming from the flames of the sacred fire that she tended" while others assume it was a convenient cover for the breaking of her vows, especially as priesthood had been forced on her.

Romulus and Remus were orderer killed by Rhea Silvia's uncle, Amulius, but were instead discarded by a river bank, to be found by the legendary She-Wolf who nurtured them. Some have speculated the wolf was a metaphor for a prostitute, as the Latin term 'lupa' (she-wolf) was colloquial for prostitute (lupanare was a standard term for a brotherl). A kindly shepherd soon found the boys and took them in, raising them, says the legend.

The Founders of Romania

The Trojans (two on the right) are declared to be the ancestors of the Romans, Aeneas specifically. Those on the left are the Greek heroes of the Trojan War - enemies of the Trojans.

In Greco-Roman legend, Aeneas (/ɪˈniːəs/; Grecian: Αἰνείας, Aineías, possibly derived from Greek αἰνή meaning "praised") was a Trojan hero, the son of the prince Anchises and the goddess Aphrodite (Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons of Ilus, founder of Troy), making Aeneas a second cousin to Priam's children (such as Hector and Paris). He is a character in Greek legend and is mentioned in Homer's Iliad. Aeneas receives full treatment in Roman legend, most extensively in Virgil's Aeneid, where he is cast as an ancestor of Romulus and Remus. He became the first true hero of Rome and the first Roman as well as a pivotal figure in Hellenism. Snorri Sturluson identifies him with the Norse god Vidarr of the Æsir, thus further connecting him to Heathenism. The Aeneid explains that Aeneas is one of the few Trojans who were not killed or enslaved when Troy fell. Aeneas, after being commanded by the gods to flee, gathered a group, collectively known as the Aeneads, who then traveled to Italia and became progenitors of Romans. The Aeneads included Aeneas's trumpeter Misenus, his father Anchises, his friends Achates, Sergestus, and Acmon, the healer Iapyx, the helmsman Palinurus, and his son Ascanius (also known as Iulus, Julus, or Ascanius Julius). He carried with him the Lares and Penates, the statues of the household gods of Troy, and transplanted them to Italia. The journey was extensive and epic, including various obstacles along the way from Troy to Italia.

King Numitor of Alba Longer, forebear of Romulus and Remus, defeating his usurper brother Amulius.

In Roman legend, King Numitor of Alba Longa, was the maternal grandfather of Rome's founder and first king, Romulus, and his twin brother Remus. He was the son of Procas, descendant of Aeneas the Trojan, and father of the twins' mother, Rhea Silvia, and Lausus. a In -40 AUC Procas died and was meant to be succeeded by Numitor. Instead he was overthrown and removed from the kingdom by his brother, Amulius, who had no respect for his father's will or his brother's seniority. Amulius also murdered his sons, in an effort to remove power from his brother for himself. Rhea Silvia was made a Vestal Virgin by Amulius rendering her unable to have children on pain of death; however, she was forcibly impregnated by the god Mars, so the legends claim. Romulus and Remus overthrew Amulius and reinstated Numitor as king in 2 AUC.

Romulus

Son of the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia, the legendary Romulus was Rome's first king and the city's founder. After he and his twin brother Remus had deposed King Amulius of Alba and reinstated the king's brother and their grandfather Numitor to the throne, they decided to build a city in the area where they had been abandoned as infants. After Remus was killed by Romulus in a dispute on where to built the first settlement, Romulus began building the city on the Palatine Hill. The controversy surrounding this brotherly murder would hang over Roman historians from the founding of the city to the present day. Many have commented that Remus' blood cursed Romania into eternal Civil War, suffering brother against brother forever.

Roman raiding party of Rome's early days - reminiscent of the Rape of the Sabines

Romulus' work began with fortifications. He permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen without distinction. He is credited with establishing the city's religious, legal and political institutions. The kingdom was established by unanimous acclaim with him at the helm when Romulus called the citizenry to a council for the purposes of determining their government. Romulus established the senate as an advisory council with the appointment of 100 of the most noble men in the community. These men he called patres and their descendants became the patricians. To project command, he surrounded himself with attendants, in particular the twelve lictors. He created three divisions of horsemen (equites), called centuries: Ramnes (Romans), Tities (after the Sabine king) and Luceres (Etruscans). He also divided the populace into 30 curiae, named after 30 of the Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. The curiae formed the voting units in the popular assemblies (Comitia Curiata).

Roman soldier, circa AUC 50s

Roman Hoplite, circa AUC 250

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as the rape of the Sabine women. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighboring tribes, the Sabines and Latins, to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The account vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines a well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius sharing the throne. In addition to the war with the Sabines, Romulus waged war with the Fidenates and Veientes and others.

He reigned for 37 or 38 years. According to the legend, Romulus vanished at age 54 while reviewing his troops on the Campus Martius. He was reported to have been taken up to Mt. Olympus in a whirlwind and made a god. After initial acceptance by the public, rumors and suspicions of foul play by the patricians began to grow. In particular, some thought that members of the nobility had murdered him, dismembered his body, and buried the pieces on their land. These were set aside after an esteemed nobleman testified that Romulus had come to him in a vision and told him that he was the god Quirinus. He became, not only one of the three major gods of Rome, but the very likeness of the city itself

After Romulus died, there was an interregnum for one year, during which ten men chosen from the senate governed Rome as successive interreges. Under popular pressure, the Senate finally chose the Sabine Numa Pompilius to succeed Romulus, on account of his reputation for justice and piety. A string of Kings of Rome followed Numa.

Tarquin the Proud

The seventh and final king of Rome was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. He was the son of Priscus and the son-in-law of Servius whom he and his wife had killed.

Tarquinius waged a number of wars against Rome's neighbours, including against the Volsci, Gabii and the Rutuli. He also secured Rome's position as head of the Latin cities. He also engaged in a series of public works, notably the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and works on the Cloaca Maxima and the Circus Maximus. However, Tarquin's reign is remembered for his use of violence and intimidation to control Rome, and his disrespect of Roman custom and the Roman Senate.

Tensions came to a head when the king's son, Sextus Tarquinius, raped Lucretia, wife and daughter to powerful Roman nobles. Lucretia told her relatives about the attack, and committed suicide to avoid the dishonour of the episode. Four men, led by Lucius Junius Brutus, and including Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, Publius Valerius Poplicola, and Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus incited a revolution that deposed and expelled Tarquinius and his family from Rome in AUC 245.

Brutus and Collatinus became Rome's first consuls, marking the beginning of the Roman Republic. This new government would survive for the next 500 years until the rise of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, and would cover a period during which Rome's authority and area of control extended to cover great areas of Europe, North Libia, and the West Asia.

The Celts

The Celts, in addition to the Latins and Etruscans, are counted as the founding peoples are modern Romania and Romans.

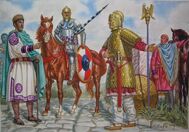

Reconstruction of Italic Celts from a dig in Patavia, in northwestern Italia, near the Adriatic

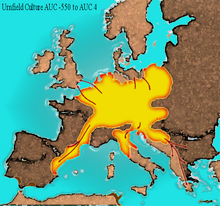

Before the rapid spread of the Tenui Culture (so named after the major archeological site in Tenui, Romania. The bearers of the Tenui Culture were the people known as Celts or Gallians to ancient ethnographers) in the 3rd century AUC, the territory of northwestern and eastern Romania already participated in the Late Bronze Age Urnfield Culture (linguistic evidence suggests that the people of the Urnfield Culture spoke a form of Italo-Celtic, perhaps originally Proto-Celtic) out of which the early iron-working Lentia Culture (commonly associated with Proto-Celtic and Celtic populations and named after Lentia, Romania) would develop.

By AUC 250, there is strong Lentia influence throughout most of Romania. Out of this Lentia background, presumably representing an early form of Continental Celtic culture, the Tenui Culture arises, presumably under Mediterranean influence from the Grecian, Phoenician, and Etruscan civilizations, spread out in a number of early centers along the Seine, the Middle Rhine and the upper Elbe.

Celtic tribes had been settled in the Alpine valleys and the areas south since well before the founding of Rome as well, expanding southwards in the direction of Rome.

The Canegrate culture may represent the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, penetrated and settled in the western Po valley.

They brought a new funerary practice—cremation—which supplanted inhumation. It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age, when North Western Italia appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artifacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture. The bearers of the Canegrate culture maintained its homogeneity for only a century, after which it melded with the Ligurian aboriginal populations and with this union gave rise to a new phase called the Golasecca culture, which is nowadays identified with the Celtic Lepontii.

Urnfield Culture spread

Livy (v. 34) has the Bituriges, Arverni, Senones, Aedui, Ambarri, Carnutes, and Aulerci led by Bellovesus, arrive in northern Italy during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus, occupying the area between Milan and Cremona. Milan (Mediolanum) itself is presumably a Gallic foundation, its name having a Celtic etymology of "[city] in the middle of the [Padanic] plain". Polybius wrote about co-existence of the Celts in northern Italia with Etruscan nations in the period before the Sack of Rome in AUC 364. Ligurian tribes were also present in Latium and in Samnium. According to Plutarch they called themselves Ambrones, which could indicate a relationship with the Ambrones of northern Europe. Little is known of the Ligurian language. Only place-names and personal names remain. It appears to be an Indo-European branch with both Italic and particularly strong Celtic affinities. Because of the strong Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were known in antiquity as Celto-Ligurians (in Greek Κελτολίγυες, Keltolígues).

The Celtic Insubres tribe of northern Italia - the namesake of the northern Italian region Insubria, here depicted fighting Greeks.

The initial Celtic settlement of the Po valley in the mid thirteenth century AUC brought the invaders hard up against the barrier of the Apennines—a barrier permeated by well-trodden routes linking the Etruscan-dominated north to the Etruscan homeland backing onto the Tyrrhenian Sea. Inevitably Celtic war bands were drawn southwards into the heart of Etruria. This occurred at the moment that Rome, expanding her power northwards, was taking over the old Etruscan cities one by one.

The whole of northern Italia would gain the term Gallia Cisalpina by the Romans, with notable tribes such as the Insubres residing there, who have given their name to northern Italia as Insubria.

The most northerly Celts of what is modern Romania were found in Raetia are surrounding areas which would later see an influx of Germanic settlers.

Little is known of the origin or history of the Raetians, who appear in the records as one of the most powerful and warlike of the Alpine tribes, expanding to what is modern Augusta, Raetia. Livy states distinctly that they were of Etruscan origin. A tradition reported by Justin and Pliny the Elder affirmed that they were a portion of that people who had settled in the plains of the Po and were driven into the mountains by the invading Celts, when they assumed the name of "Raetians" from an eponymous leader Raetus. Even if their Etruscan origin be accepted, at the time when the land became known to the Romans, Celtic tribes were already in possession of it and had amalgamated so completely with the original inhabitants that, generally speaking, the Raetians of later times may be regarded as a Celtic people, although non-Celtic tribes (es. Euganei) were settled among them.

The Euganei (fr. Lat. Euganei, Euganeorum; cf. Gr. εὐγενής (eugenēs) 'well-born') were a Proto-Italic ethnic group that dwelt an area among Adriatic Sea and Rhaetian Alps. Subsequently, they were driven by the Adriatic Veneti to an area between the river Adesa and Lake Lariu, where they remained until the early Roman Empire. They may have been a Pre-Indo-European people, ethnically related to the Ingauni, as suggested by the similarity of the names. According to Pliny the Elder the Stoni people from northern Venetu et Histria were of the same stock as the Euganei.

The First Roman Republic[]

Eurasia circa AUC 450

According to tradition and later writers such as Livy, the Roman Republic was established around AUC 245, when the last of the seven kings of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed by Lucius Junius Brutus, and a system based on annually elected magistrates and various representative assemblies was established. A constitution set a series of checks and balances, and a separation of powers. The most important magistrates were the two consuls, who together exercised executive authority as imperium, or military command. The consuls had to work with the senate, which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or patricians, but grew in size and power. In the 4th century AUC the Republic came under attack by the Gallians, who initially prevailed and sacked Rome. The Romans then took up arms and drove the Celts back, led by Camillus. The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans. The last threat to Roman hegemony in Italia came when Tarentum, a major Greek colony, enlisted the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus in AUC 473, but this effort failed as well.

AUC 354 (1) Aristocratic Rasenna woman, (2) Rasenna hoplite from Velzna, (3) Rasenna hoplite from Tutere

From the 200s AUC through the 500s the Roman Republic expanded from the city in the hills to control the length of Italia, fighting the Celts who lived in the north of Italia, the Etruscans, and the various Italic peoples to their south and east, such as the Samnites.

Battle of Telamon, AUC 529 - A coalition of Cisalpine Gallic tribes, from northern Italia, battling with Legions of the First Republic

The First Republic was in a state of quasi-perpetual war throughout its existence. The Republic nonetheless demonstrated extreme resilience and always managed to overcome its losses, however catastrophic. After the Gallic Sack of Rome, Romania conquered the whole Italian peninsula in a century, which turned the Republic into a major power in the Mediterranean.

In the 5th century AUC Rome had to face a new and formidable opponent: the powerful Phoenician city-state of Carthage.

With Carthage defeated, Romania would become the dominant power of the ancient Mediterranean world. It then embarked on a long series of difficult conquests, after having notably defeated Philip V and Perseus of Macedon, Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire, the Lusitanian Viriathus, the Numidian Jugurtha, the Pontic king Mithridates VI, the Gallian Vercingetorix, and the Egyptian queen Cleopatra.

Pyrrhic War

The Pyrrhic Wars occured from 474 to 479, fought by Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus. Pyrrhus was asked by the people of the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italia to help them in their war with the Roman Republic.

The Grecian forces of Epirus were able to employ armored elephants against the Romans, who were unused to the animals.

Battle of Beneventum (AUC 479), Roman Legions (left) against the Phalanx of Epirus (right)

A skilled commander, with a strong army fortified by war elephants (which the Romans were not experienced in facing), Pyrrhus enjoyed initial success against the Roman legions, but suffered heavy losses even in these victories. Plutarch wrote that Pyrrhus said after the second battle of the war, "If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined." He could not call up more men from home and his allies in Italy were becoming indifferent. The Romans, by contrast, had a very large pool of military manpower and could replenish their legions even if their forces were depleted in many battles.

This has led to the expression Pyrrhic victory, a term for a victory that inflicts losses the victor cannot afford in the long term. Worn down by the battles against Rome, Pyrrhus moved his army to Trinacria to war against the Carthaginians instead. After several years of campaigning there, he returned to Romania in AUC 479, where the last battle of the war was fought, ending in Roman victory. Following this, Pyrrhus returned to Epirus, ending the war. Three years later the Romans captured Tarentum. The Pyrrhic War was the first time that Rome confronted the professional mercenary armies of the Grecian states of the eastern Mediterranean.

The Romans first facing of the war-elephant occured during Pyrrhus' invasion and at first these animals unsettled the legions. A tactic famously developed, however, where the Romans would use chariots and rope to ride a circle aroudn the elephant's legs, thereby tying them up and tripped them. Ultimately the beasts became fairly simple to deal with by a variety of tactics.

Rome's victory drew the attention of these states to the emerging power of Rome. Ptolemy II, the king of Egypt, established diplomatic relations with Rome. After the war, Rome asserted its hegemony over southern Italia and cast glances eastwards, to have resounding impacts on the Grecian world.

The Macedonian Wars

Sandwiched between the war against Epirus and that against Carthage was the other instrumental conflict in Romania's early growth beyond the Italian peninsula. The Macedonian Wars (540 - 606) were a series of conflicts fought by the First Roman Republic and its Grecian allies in the eastern Mediterranean against several different major Greek kingdoms.

They resulted in Roman control or influence over the eastern Mediterranean basin, in addition to their hegemony in the western Mediterranean after the Punic Wars. Traditionally, the "Macedonian Wars" include the four wars with Macedonia, in addition to one war with the Seleucid Empire, and a final minor war with the Achaean League (which is often considered to be the final stage of the final Macedonian war).

The Romans (left) came against the famous Greek phalanx (right) during the Macedon Wars, besting the once dominant military tactic.

The most significant war was fought with the Seleucid Empire, while the war with Macedonia was the second, and both of these wars effectively marked the end of these empires as major world powers, even though neither of them led immediately to overt Roman domination. Four separate wars were fought against the weaker power, Macedonia, due to its geographic proximity to Rome, though the last two of these wars were against haphazard insurrections rather than powerful armies. Roman influence gradually dissolved Macedonian independence and digested it into what was becoming a leading global empire. The outcome of the war with the now-deteriorating Seleucid Empire was ultimately fatal to it as well, though the growing influence of Persian Parthia and Pontus prevented any additional conflicts between it and Rome. From the close of the Macedonian Wars until the early First Roman Empire, the eastern Mediterranean remained an ever shifting network of polities with varying levels of independence from, dependence on, or outright military control by, Rome. According to Polybius, who sought to trace how Rome came to dominate the Grecian east in less than a century, Rome's wars with Grecia were set in motion after several Greek city-states sought Roman protection against the Macedonian Kingdom and Seleucid Empire in the face of a destabilizing situation created by the weakening of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Battle of Cynoscephalae (AUC 557) pitted the Roman Republic's Legions (left) against the Greek forces of the Kingdom of Macedonia (right)

In contrast to the west, the Greek east had been dominated by major empires for centuries, and Roman influence and alliance-seeking led to wars with these empires that further weakened them and therefore created an unstable power vacuum that only Romania was capable of pacifying. This had some important similarities (and some important differences) to what had occurred in Italia centuries earlier, but was this time on a continental scale.

Historians see the growing Roman influence over the east, as with the west, not as a matter of intentional empire-building, but constant crisis management narrowly focused on accomplishing short-term goals within a highly unstable, unpredictable, and inter-dependent network of alliances and dependencies. With some major exceptions of outright military rule (such as parts of mainland Grecia), the eastern Mediterranean world remained an alliance of independent city-states and kingdoms (with varying degrees of independence, both de jure and de facto) until it transitioned into the Roman Empire. It wasn't until the time of the First Roman Empire that the eastern Mediterranean, along with the entire Roman world, was organized into provinces under explicit Roman control.

The Punic Wars

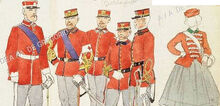

Roman soldier, AUC 696

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from AUC 490 to 608. At the time, they were some of the largest wars that had ever taken place. The term Punic comes from the Latin word Punicus (or Poenicus), meaning "Carthaginian", with reference to the Carthaginians' Phoenician ancestry. The main cause of the Punic Wars was the conflicts of interest between the existing Carthaginian Empire and the expanding Roman Republic. The Romans were initially interested in expansion via Sicilia (which at that time was a cultural melting pot), part of which lay under Carthaginian control. At the start of the First Punic War, Carthage was the dominant power of the Western Mediterranean, with an extensive maritime empire. Rome was a rapidly ascending power in Italia, but it lacked the naval power of Carthage. The Second Punic War witnessed Hannibal's famous crossing of the Alps from Hispania, elephants and army with him, in AUC 538, followed by a prolonged but ultimately failed campaign of Carthage's Hannibal in mainland Italia. By the end of the Third Punic War, after more than a hundred years and the loss of many hundreds of thousands of soldiers from both sides, Romania had conquered Carthage's empire, completely destroyed the city, and became the most powerful state of the Western Mediterranean. With the end of the Macedonian Wars – which ran concurrently with the Punic Wars – and the defeat of the Seleucid King Antiochus III the Great in the Roman–Seleucid War in the eastern sea, Romania emerged as the dominant Mediterranean power and one of the most powerful realms in the world.

Carthaginian elephants charge down Roman legions during the Punic Wars

In the three Punic Wars, Carthage was eventually destroyed and Rome gained control over Hispania, Sicilia and North Libia. After defeating the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires in the 6th century AUC, the Romans became the dominant people of the Mediterranean Sea. The conquest of the Grecian kingdoms provoked a fusion between Roman and Greek cultures and the Roman elite, once rural and rugged, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. By this time Rome was a consolidated empire – in the military view – and had no major enemies. Roman armies occupied Hispania in the mid 6th century AUC but encountered stiff resistance from that time down to the age of Augustus. The Celtiberian stronghold of Numantia became the centre of Hispanian resistance to Rome in the AUC 610s and 630s. Numantia fell and was completely razed to the ground in AUC 622. The conquest of Hispania was completed in AUC 735 — but at heavy cost and severe losses.

Eurasia circa AUC 650

Toward the mid 7th century AUC, a huge migration of Germanic tribes took place, led by the Cimbri and the Teutones. These tribes overwhelmed the peoples with whom they came into contact and posed a real threat to Rome itself. At the Battle of Aquae Sextiae and the Battle of Vercellae the Germans were virtually annihilated, which ended the threat. In these two battles the Teutones and Ambrones are said to have lost 290,000 men (200,000 killed and 90,000 captured); and the Cimbri 220,000 men (160,000 killed, and 60,000 captured).

The Gallic Wars

The figure of Julius Caesar would gain fame over the course of the Gallic Wars - a series of military campaigns waged by the Roman proconsul against several Gallic tribes. Rome's war against the Gallic tribes lasted from 696 to 704 and culminated in the decisive Battle of Alesia in 706, in which a complete Roman victory resulted in the expansion of the Roman Republic over the whole of Gallia. While militarily just as strong as the Romans, the internal division between the Gallic tribes helped ease victory for Caesar, and Vercingetorix's attempt to unite the Gallians against Roman invasion came too late. The wars paved the way for Julius Caesar to become the sole ruler of the Roman Republic.

Model of the Roman siege of Avaricum

The Gallic Wars were a series of military campaigns waged by the Roman proconsul Julius Caesar against numerous Gallic tribes between 696 and 704. While militarily just as strong as the Romans, the Gallic tribes' internal divisions helped ease victory for Caesar, and Vercingetorix's attempt to unite the Celts against Roman invasion came too late. Although Caesar portrayed the invasion as being a preemptive and defensive action, most historians agree that the wars were fought primarily to boost Caesar's political career and to pay off his massive debts. Still, Gallia was of significant military importance to the Romans, as they had been attacked several times by native tribes both indigenous to Gallia and farther to the north. Conquering Gallia allowed Rome to secure the natural border of the river Rhine. The union of Rome and Gallia would create a markedly different culture and nation and this fusion would shape the Romans all the way to the present day, changing the Roman focus to a western one and tying it to Western Europe as a Celto-Latinic culture and nation.

Gallic warriors attacking the Romans during the Siege of Alesia

The wars began with conflict over the migration of the Helvetii, which would draw in neighboring tribes and the Germanic Suebi as well. Caesar had resolved to conquer all of Gallia, and led campaigns in the east, where he was nearly defeated by the Nervii. Caesar defeated the Veneti in a naval battle and took most of northwest Gallia. Caesar sought to boost his public image, and undertook first of their kind expeditions across the Rhine river and British Channel. Upon his return from Britannia, Caesar was hailed as a hero, though he had achieved little beyond landing because his army had been too small. The next year, he went back with a proper army and conquered much of Britannia. However, tribes began to rise up on the continent, and the Romans suffered several humiliating defeats. AUC 701 saw a draconian campaign against the Gallians to attempt to pacify them. This failed, and the Gallians rose up in mass revolt under leadership of Vercingetorix. The Gallians won a notable victory at the Battle of Gergovia, but were utterly defeated by the Roman's indomitable siege works at the Battle of Alesia.

Roman veteran soldier during the Siege of Alesia

By 704 there was little resistance and Caesar's troops mostly were mopping up. Gallia was conquered, although it would not become a Roman province until 727, and resistance would continue as late as 684. There is no clear end-date for the war, but the imminent Roman Civil War led to the pulling out of Caesar's troops in 704. Caesar's wild successes in the war had made him extremely wealthy, and provided a legendary reputation. The Gallic Wars were a key factor in Caesar's ability to win the Civil War and declare himself dictator, in what would eventually lead to the end of the Roman Republic and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

The Gallic Wars are described by Julius Caesar in his book Commentarii de Bello Gallico, which is the main source for the conflict but is considered to be unreliable at best by modern historians. Caesar and his contemporaries makes impossible claims about the number of Gallians killed (over a million), while claiming almost zero Roman casualties. Modern historians believe that Gallic forces were far smaller than claimed by the Romans, and that the Romans actually suffered tens of thousands of casualties. Historians regard the entire account as clever propaganda meant to boost Caesar's image, and suggests that it is of minimal historical accuracy. The campaign was still exceptionally brutal, and untold numbers of Gallians were killed or enslaved, including large numbers of non-combatants, who were spread across the Roman realm.

Antonius' Civil War

Roman bust dating to the late First Republic, found in south-central Romania in 2760. Believed to represent Julius Caesar.

In the 8th century AUC the Republic faced a period of political crisis and social unrest. Into this turbulent scenario emerged the figure of Julius Caesar. Caesar reconciled the two more powerful men in Rome: Marcus Licinius Crassus, his sponsor, and Crassus' rival, Pompey. The First Triumvirate had satisfied the interests of these three men: Crassus, the richest man in Rome, became richer; Pompey exerted more influence in the Senate; and Caesar held consulship and military command in Gallia.

Caesar's Veteran soldiers

In AUC 701, the Triumvirate disintegrated at Crassus' death. Crassus met his end in Persia. Crassus had received Syria as his province, which promised to be an inexhaustible source of wealth. It might have been, had he not also sought military glory and crossed the Euphrates in an attempt to conquer Parthia. Crassus attacked Parthia not only because of its great source of riches, but because of a desire to match the military victories of his two major rivals, Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar. The king of Armenia, Artavazdes II, offered Crassus the aid of nearly 40,000 troops (10,000 cataphracts and 30,000 infantrymen) on the condition that Crassus invade through Armenia so that the king could not only maintain the upkeep of his own troops but also provide a safer route for his men and Crassus'. Crassus refused, and chose the more direct route by crossing the Euphrates, as he had done in his successful campaign in the previous year. Crassus received directions from the Osroene chieftain Ariamnes, who had previously assisted Pompey in his eastern campaigns. Ariamnes was in the pay of the Parthians and urged Crassus to attack at once, falsely stating that the Parthians were weak and disorganized. He then led Crassus' army into desolate desert, far from any water. In 701 at the Battle of Carrhae Crassus' legions were defeated by a numerically inferior Parthian force. Crassus' legions were primarily heavy infantry but were not prepared for the type of swift, cavalry-and-arrow attack in which Parthian troops were particularly adept. The Parthian horse archers devastated the unprepared Romans with hit and run techniques and feigned retreats with the ability to shoot as well backwards as they could forwards. Crassus refused his quaestor Gaius Cassius Longinus's plans to reconstitute the Roman battle line, and remained in the testudo formation to protect his flanks until the Parthians eventually ran out of arrows. However, the Parthians had stationed camels carrying arrows to allow their archers to continually reload and relentlessly barrage the Romans until dusk. Despite taking severe casualties, the Romans successfully retreated to Carrhae, forced to leave many wounded behind to be later slaughtered by the Parthians.

Subsequently Crassus' men, being near mutiny, demanded he parley with the Parthians, who had offered to meet with him. Crassus, despondent at the death of his son Publius in the battle, finally agreed to meet the Parthian general Surena; however, when Crassus mounted a horse to ride to the Parthian camp for a peace negotiation, his junior officer Octavius suspected a Parthian trap and grabbed Crassus' horse by the bridle, instigating a sudden fight with the Parthians that left the Roman party dead. A story emerged that the Parthians poured molten gold into the captured Crassus' mouth as a symbol of his thirst for wealth, though its uncertain if this is a true story or not and Crassus may have died in the melee that had occurred prior.

Crassus had acted as mediator between Caesar and Pompey, and, without him, the two generals began to fight for power. After being victorious in the Gallic Wars and earning respect and praise from the legions, Caesar was a clear menace to Pompey, that tried to legally remove Caesar's legions. To avoid this, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River and invaded Rome in AUC 705 sparking a Civil War.

Caesar's Civil War

Julius Caesar, undoubtedly among the most famous Romans in history.

Running from 705–709, this was one of the last politico-military conflicts in the Roman Republic before the establishment of the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations, between Julius Caesar, his political faction (broadly known as Populares), and his legions, against the Optimates (or Boni), the politically conservative and socially traditionalist faction of the Roman Senate, who were supported by Pompey and his legions.

Prior to the war, Caesar had served for eight years in the Gallic Wars. He and Pompey had, along with Marcus Licinius Crassus, established the First Triumvirate, through which they shared power over Rome. Caesar soon emerged as a champion of the common people, and advocated a variety of reforms. The Senate, fearful of Caesar, reduced the number of legions he had, then demanded that he relinquish command of his army. Caesar refused, and instead marched his army on Rome, which no Roman general was permitted to do by law. Pompey fled Rome and organized an army in the south of Italia to meet Caesar.

The war was a four-year-long politico-military struggle, fought in Italia, Illyria, Grecia, Egypt, Libia, and Hispania. Pompey defeated Caesar in 706 at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, but was himself defeated much more decisively at the Battle of Pharsalus. The Optimates under Marcus Junius Brutus and Cicero surrendered after the battle, while others, including those under Cato the Younger and Metellus Scipio fought on. Pompey fled to Egypt and was killed upon arrival, an assassination which angered Caesar who had displayed himself as the great reconciliator, more often bringing his defeated foes back to their feet and into his good graces. Scipio was defeated in 708 at the Battle of Thapsus in North Libia. He and Cato committed suicide shortly after the battle. The following year, Caesar defeated the last of the Optimates under his former lieutenant Labienus in the Battle of Munda and became Dictator perpetuo (Dictator in perpetuity or Dictator for life) of Rome. The changes to Roman government concomitant to the war mostly eliminated the political traditions of the Roman Republic and led to the Roman Empire.

After assuming control of government, Caesar began a program of social and governmental reforms, including the creation of the Julian calendar. He gave citizenship to many residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He initiated land reform and support for veterans. He centralized the bureaucracy of the Republic and was eventually proclaimed "dictator for life" (Latin: "dictator perpetuo"). His populist and authoritarian reforms angered the elites, who began to conspire against him. On the Ides of March (15 March), 710, Caesar was assassinated by a group of rebellious senators called the Liberatores led by Brutus and Cassius, who stabbed him to death. A new series of civil wars broke out and the constitutional government of the Republic was never fully restored.

Eurasia circa AUC 700

Marcus Antonius

Caesar's assassination caused political and social turmoil in Rome; without the dictator's leadership, the city was ruled by his friend and colleague, Marcus Antonius. Octavius (Caesar's adopted son), along with general Marcus Antonius and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Caesar's best friend, established the Second Triumvirate. Lepidus was forced to retire in AUC 718 after betraying Octavian in Sicilia. Antonius settled in Egypt with his lover, Pharaoh, or Queen, Cleopatra VII Philopator of Egypt. Marcus Antonius' affair with Cleopatra was seen as an act of treason, since she was queen of a foreign power and Antonius was adopting an extravagant and Hellenistic lifestyle that was considered inappropriate for a Roman statesman.

Following Antonius' Donations of Alexandria, which gave to Cleopatra the title of "Queen of Kings", and to their children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, the war between Octavian and Marcus Antonius broke out. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the Battle of Actium in AUC 723. Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra committed suicide, leaving Octavianus the sole ruler of the Republic.

After the Battle of Actium, the period of major naval battles was over and the Romans possessed unchallenged naval supremacy in the Germanic Sea, Atlantic coasts, Mediterranean, Red Sea, and the Black Sea until the emergence of new naval threats in the form of the Franks and the Saxons in the Germanic Sea, and in the form of Borani, Herules and Goths in the Black Sea.

The First Roman Empire[]

Roman statesman and military leader who became the first emperor of the Roman Empire, Augustus

In AUC 727, Octavian was the sole Roman leader. His leadership brought the zenith of the Roman civilization, that lasted for four decades. In that year, he took the name Augustus. That event is usually taken by historians as the beginning of Roman Empire. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers. The Senate granted Octavian a unique grade of Proconsular imperium, which gave him authority over all Proconsuls.

The unruly provinces at the borders, where the vast majority of the legions were stationed, were under the control of Augustus. These provinces were classified as imperial provinces. The peaceful senatorial provinces were under the control of the Senate. The Roman legions, which had reached an unprecedented number (around 50) because of the civil wars, were reduced to 28.

Under Augustus' rule, Roman literature grew steadily in the Golden Age of Latin Literature. Poets like Vergil, Horace, Ovid and Rufus developed a rich literature, and were close friends of Augustus. Along with Maecenas, he stimulated patriotic poems, as Vergil's epic Aeneid and also historiographical works, like those of Livy. Augustus' enlightened rule resulted in a 200 years long peaceful and thriving era for the Empire, known as Pax Romana.

Battle of the Teutoburg AUC 762

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (Frankish: Schlacht va Teutoburger Wal) took place in in AUC 762, when an alliance of Germanic tribes ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius Varus. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses. Despite several successful campaigns and raids by the Romans in the years after the battle, they never again attempted to conquer the Germanic territories that far east of the Rhine river. The victory of the Germanic tribes against Rome's legions in the Teutoburg Forest would have far-reaching effects on the subsequent history of both the ancient Germanic peoples and the Roman Empire. Contemporary and modern historians have generally regarded Arminius' victory over Varus as "Rome's greatest defeat", making it one of the rarest things in history, a truly decisive battle, and as "a turning-point in world history".

Roman naval games in the amphitheater, circa AUC 700s

Despite its military strength, the Empire made few efforts to expand its already vast extent; the most notable being the conquest of Britannia, begun by emperor Claudius, and emperor Trajan's conquest of Dacia (AUC 854 to 859). Roman legions were also employed in intermittent warfare with the Germanic tribes to the north and the Parthian, or Persian, Empire to the east. Meanwhile, armed insurrections (e.g., the Hebraic insurrection in Judea) and brief civil wars (e.g., in AUC 821 the Year of the Four Emperors) demanded the legions' attention on several occasions. Julio-Claudian Dynasty

Roman Legion AUC 762

From AUC 767 to 821 Romania was under the Julio-Claudian dynasty, descending from the first Emperor, Augustus. These were Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. Gaius, better known as "Caligula" ("little boots") was a son of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder. Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late AUC 790 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as encephalitis, which can cause mental derangement, hyperthyroidism, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position). Whatever the cause, there was an obvious shift in his reign from this point on, leading his biographers to label him as insane. Caligula was known for his torture-executions wantonly done as well as such incidents as inviting Senators to dinner only to take their wives away and then return to the table, explaining in full detail what sexual adventures they had had. Most of what history remembers of Caligula comes from Suetonius, in his book Lives of the Twelve Caesars. According to Suetonius, Caligula once planned to appoint his favourite horse Incitatus to the Roman Senate. He ordered his soldiers to invade Britannia to fight the Sea God Neptune, but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of Gallia instead. It is believed he carried on incestuous relations with his three sisters: Julia Livilla, Drusilla and Agrippina the Younger. He ordered a statue of himself to be erected in Herod's Temple at Jerusalem, which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded from this plan by his friend king Agrippa I. He ordered people to be secretly killed, and then called them to his palace. When they did not appear, he would jokingly remark that they must have committed suicide.

Caligula, Roman Emperor

In AUC 794, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife Caesonia and their daughter Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.

Claudius followed Caligula as emperor. He was a younger brother of Germanicus, and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability. He improved the bureaucracy and streamlined the citizenship and senatorial rolls. Claudius was also an excellent orator despite being made what amounted to a pseudo court jester by Caligula due to Claudius’ stutter and supposed simple mindedness.

Claudius, during his rule, ordered the construction of a winter port at Ostia Antica for Rome, thereby providing a place for grain from other parts of the Empire to be brought in inclement weather.

Sculpture of Agrippina crowning her young son Nero (c. AUC 810)

Claudius ordered the suspension of further attacks across the Rhine, setting what was to become the permanent limit of the Empire's expansion in that direction. In 796, he resumed the Roman conquest of Britannia that Julius Caesar had begun and incorporated more Eastern provinces into the empire.

Roman vase dated between AUC 750 and 780

In his own family life, Claudius was less successful.

After her accession to power, Claudius’ wife Messalina enters history with a reputation as ruthless, predatory and sexually insatiable, while Claudius is painted as easily led by her and unconscious of her many adulteries. Valeria Messalina targeted especially the female members of Claudius’ family for exile or execution. Messalina was reputed to have held a competition with a well known prostitute in Rome to see who could have sex with the most men in a single day - a competition that Messalina was said to have won.

His wife Messalina cuckolded him and moved to secretly marry a new man, supposedly with the plans of replacing Claudius as emperor; when he found out, he had her executed and married his niece, Agrippina the Younger. She, along with several of his freedmen, held an inordinate amount of power over him, and although there are conflicting accounts about his death, she may very well have poisoned him in 807. Claudius was deified later that year. The death of Claudius paved the way for Agrippina's own son, the 17-year-old Lucius Domitius Nero.

Emperor Nero

Nero ruled from 807 to 821. During his rule, Nero focused much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and increasing the cultural capital of the empire. He ordered the building of theatres and promoted athletic games. His reign included the Roman–Parthian War (a successful war and negotiated peace with the Parthian Empire (811–816) ), the suppression of a revolt led by Boudica in Britannia (813–814) and the improvement of cultural ties with Grecia. However, he was egotistical and had severe troubles with his mother, who he felt was controlling and over-bearing. After several attempts to kill her, he finally had her stabbed to death. He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called Domus Aurea was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome (AUC 817). Because of the convenience of this many believe that Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire, spawning the legend of him fiddling while Rome burned which is almost certainly untrue. The Domus Aurea was a colossal feat of construction that covered a huge space and demanded new methods of construction in order to hold up the gold, jewel encrusted ceilings. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

A military coup drove Nero into hiding. Facing execution at the hands of the Roman Senate, he reportedly committed suicide in AUC 821. According to Cassius Dio, Nero's last words were "Jupiter, what an artist perishes in me!"

Year of the Four Emperors

Since he had no heir, Nero's suicide was followed by a brief period of civil war, known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Between June 821 and December 822, Romania witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first ruler of the Flavian dynasty.

Vitellius

Suetonius, whose father had fought for Otho at Bedriacum, gives an unfavourable account of Vitellius' brief administration: he describes him as unambitious and notes that Vitellius showed indications of a desire to govern wisely, but that Valens and Caecina encouraged him in a course of vicious excesses which threw his better qualities into the background. Vitellius is described as lazy and self-indulgent, fond of eating and drinking, and an obese glutton, eating banquets four times a day and feasting on rare foods he would send the Roman navy to procure. For these banquets, he had himself invited over to a different noble's house for each one. He is even reported to have starved his own mother to death—to fulfill a prophecy that he would rule longer if his mother died first; alternatively there is a report that his mother asked for poison to commit suicide—a request he granted. Suetonius additionally remarks that Vitellius' besetting sins were luxury and cruelty. Other writers, namely Tacitus and Cassius Dio, disagree with some of Suetonius' assertions, even though their own accounts of Vitellius are scarcely positive ones.

Despite his short reign he made two important contributions to Roman government which outlasted him. Tacitus describes them both in his Histories: Vitellius ended the practice of centurions selling furloughs and exemptions of duty to their men, a change Tacitus describes as being adopted by 'all good emperors'. He also expanded the offices of the Imperial administration beyond the imperial pool of freedmen, allowing those of the Equites to take up positions in the Imperial civil service.

Lorica segmentata examination

Vitellius also banned astrologers from Rome and Italy on 1 October 69. Some astrologers responded to his decree by anonymously publishing a decree of their own: "Decreed by all astrologers in blessing on our State Vitellius will be no more on the appointed date." In response, Vitellius executed any astrologers he came across.

Furthermore, Vitellius continued Otho's policies in regard to Nero's memory, in that he honored the dead emperor and sacrificed to his spirit. He also had Nero's songs performed in public, and attempted to imitate Nero who remained extremely popular among the lower classes of the Roman Empire

Virellius was Roman emperor for eight months, from 16 April to 22 December. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil war. Vitellius was the first to add the honorific cognomen Germanicus to his name instead of Caesar upon his accession. Like his direct predecessor, Otho, Vitellius attempted to rally public support to his cause by honoring and imitating Nero who remained widely popular in the empire.

Roman Legions facing Germanic tribes along the northern fringes of the Empire

The military and political anarchy created by this civil war had serious implications, such as the outbreak of the Batavian rebellion. These events showed that a military power alone could create an emperor. Augustus had established a standing army, where individual soldiers served under the same military governors over an extended period of time. The consequence was that the soldiers in the provinces developed a degree of loyalty to their commanders, which they did not have for the emperor. Thus the Empire was, in a sense, a union of inchoate principalities, which could have disintegrated at any time.

Roman legion, 9th century AUC

Through his sound fiscal policy, the emperor Vespasian was able to build up a surplus in the treasury, and began construction on the Colosseum. Titus, Vespasian's successor, quickly proved his merit, although his short reign was marked by disaster, including the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished Colosseum, but died in AUC 834. His brother Domitian succeeded him. Having exceedingly poor relations with the Senate, Domitian was murdered in September 849.

Roman legion, circa AUC 850s

The Flavian Dynasty, although a relatively short-lived dynasty, helped restore stability to an empire on its knees. Although all three Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian) have been criticised, especially based on their more centralised style of rule, they issued reforms that created a stable enough empire to last. However, their background as a military dynasty led to further marginalisation of the senate, and a conclusive move away from princeps, or first citizen, and toward imperator, or emperor. The Five Good Emperors

Dacian Wars, AUC 855

The next century came to be known as the period of the Five Good Emperors, in which the succession was peaceful and the Empire prosperous. The emperors of this period were Nerva (849–850), Trajan (851–870), Hadrian (870–891), Antoninus Pius (891–914) and Marcus Aurelius (914–933), each one adopted by his predecessor as his successor during the former's lifetime. While their respective choices of successor were based upon the merits of the individual men they selected rather than dynastic, it has been argued that the real reason for the lasting success of the adoptive scheme of succession lay more with the fact that none but the last had a natural heir.

Roman Legions fighting the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judea, AUC 885

Trajan

Upon his accession to the throne, Trajan prepared and launched a carefully planned military campaign in Dacia. In AUC 854, Trajan personally crossed the Danube and defeated the armies of the Dacian king Decebalus at Tapae. The emperor decided not to press on toward a final conquest as his armies needed reorganisation, but he did impose very hard peace conditions on the Dacians. At Rome, Trajan was received as a hero and he took the name of Dacicus. Decebalus complied with the terms for a time, but before long he began inciting revolt. In 858, Trajan once again invaded and after a yearlong campaign ultimately defeated the Dacians by conquering their capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia. King Decebalus, cornered by the Roman cavalry, eventually committed suicide rather than being captured and humiliated in Rome. The conquest of Dacia was a major accomplishment for Trajan, who ordered 123 days of celebration throughout the empire. He also constructed Trajan's column in Rome to glorify the victory.

Eurasia circa AUC 850

In AUC 865, Trajan was provoked by the decision of Osroes I of Parthia (or Persia) to put his own nephew Axidares on the throne of the Kingdom of Armenia. The Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia was a branch of the Parthian royal family, established in AUC 807. Since then, the two great empires had shared hegemony of Armenia. The encroachment on the traditional Roman sphere of influence by Osroes ended the peace which had lasted for some 50 years.

Trajan marched first on Armenia. He deposed the king and annexed it to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Persia itself, taking the cities of Babylon, Seleucia and finally the capital of Ctesiphon in 869, while suppressing a Jewish uprising across the region. He continued southward to the Persian Gulf, whence he declared Mesopotamia a new province of the empire and lamented that he was too old to follow in the steps of Alexander the Great and continue his march eastward.

In AUC 869, he captured the great city of Susa. He deposed the Osroes I and put his own puppet ruler Parthamaspates on the throne. During his rule, the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent it had known up to that point.

Hadrian would succeed Trajan. Despite his own excellence as a military administrator, Hadrian's reign was marked more by the defense of the empire's vast territories, rather than major military conflicts. He surrendered Trajan's conquests in Mesopotamia, considering them to be indefensible. There was almost a war with Vologases III of Parthia around 874, but the threat was averted when Hadrian succeeded in negotiating a peace. Hadrian's army crushed the Bar Kokhba revolt, a massive Jewish uprising in Judea.

Emperor Hadrian reconstruction

Hadrian was the first emperor to extensively tour the provinces, donating money for local construction projects as he went. In Britannia, he ordered the construction of a wall, the famous Hadrian's Wall as well as various other such defences in Germania and Northern Libia. His domestic policy was one of relative peace and prosperity.

The Philosopher Emperor

A Roman bust of Hadrian

After Hadrian and Antonius Pius the empire would come under the reign of Marcus Aurelius. During his reign Germanic tribes and other people launched many raids along the long north European border, particularly into Gallia and across the Danube—Germans, in turn, may have been under attack from more warlike tribes farther east, driving them into the empire. His campaigns against them are commemorated on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. In Asia, a revitalised Parthian Empire renewed its assault. Marcus Aurelius sent his co-emperor Lucius Verus to command the legions in the East. Lucius was authoritative enough to command the full loyalty of the troops, but already powerful enough that he had little incentive to overthrow Marcus. The plan succeeded — Verus remained loyal until his death, while on campaign, in 922.

Daily life, mid-Classical Era

The Marcomannic Wars (Latin: bellum Germanicum et Sarmaticum, "German and Sarmatian War") were a series of wars lasting over a dozen years from about 919 until 933 that occured during Marcus Aurelius' reign. These wars pitted the Roman Empire against, principally, the Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi and the Sarmatian Iazyges; there were related conflicts with several other barbarian peoples along both sides of the whole length of the Roman Empire's northeastern European border, the river Danube. The struggle against the Germans and Sarmatians occupied the major part of the reign of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, and it was during his campaigns against them that he started writing his philosophical work Meditations. Secure for many years following his ascension to power, the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius never left Italia; neither did he embark on substantial conquests, all the while allowing his provincial legates to command his legions entirely.It is posited that Pius's reluctance to take aggressive military action throughout his reign may have contributed to Parthian territorial ambitions. The resulting war between Parthia and Rome lasted from 915 to 919 (under the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus) and, although it ended successfully, its unforeseen consequences for the Empire were great. The returning troops brought with them a plague (the so-called Antonine Plague), which would eventually kill an estimated 7 to 8 million people, severely weakening the Empire.

24th century Roman depiction of Hadrian

Vibia Sabina, wife of Hadrian

At the same time, in Central Europe the first movements of the Great Migrations were occurring, as the Goths began moving south-east from their ancestral lands at the mouth of River Vistula, putting pressure on the Germanic tribes from the north and east. As a result, Germanic tribes and other nomadic peoples launched raids south and west across Rome's northern border, particularly into Gallia and across the Danube. Whether this sudden influx of peoples with which Marcus Aurelius had to contend was the result of climate change or overpopulation remains unknown. Theories exist that the various Germanic tribes along the periphery of the Empire may have conspired to test Roman resolve as part of an attempt to bring to possible fruition, Arminius's dream of a future united Germanic empire. Up until these subsequent wars, the Marcomanni and Quadi generally enjoyed amicable relations and access to the Empire's wares—archaeological evidence of Roman household goods and practices illustrate such contact. As with almost all areas within the Empire's reach, the Romans aimed for a combination of military-territorial dominance, while at the same time, engaging in mutually beneficial commerce.

Beginning in 915 an invasion of Chatti and Chauci in the provinces of Raetia and Germania Superior was repulsed. In late 919 a force of 6,000 Langobardi and Lacringi invaded Pannonia. This invasion was defeated by local forces (vexillations of the Legio I Adiutrix commanded by a certain Candidus and the Ala Ulpia contariorum commanded by Vindex) with relative ease, but they marked the beginning of what was to come. In their aftermath, the military governor of Pannonia, Marcus Iallius Bassus, initiated negotiations with 11 tribes. In these negotiations, the Marcomannic king Ballomar, a Roman client, acted as a mediator. In the event, a truce was agreed upon and the tribes withdrew from Roman territory, but no permanent agreement was reached. In the same year, Vandals (Astingi and Lacringi) and the Sarmatian Iazyges invaded Dacia, and succeeded in killing its governor, Calpurnius Proculus. To counter them, Legio V Macedonica, a veteran unit of the Parthian campaign, was moved from Moesia Inferior to Dacia Superior, closer to the enemy.

The Roman Governor of Pannonia receives the Marcomannic surrender

The most important and dangerous invasion, however, was that of the Marcomanni in the west. Their leader, Ballomar, had formed a coalition of Germanic tribes. They crossed the Danube and won a decisive victory over a force of 20,000 Roman soldiers near Carnuntum, in what is sometimes known the Battle of Carnuntum. Ballomar then led the larger part of his host southwards towards Italia, while the remainder ravaged Noricum. The Marcomanni razed Opitergium and besieged Aquileia. This was the first time that hostile forces had entered Italy since 653, when Gaius Marius defeated the Cimbri. The army of praetorian prefect Titus Furius Victorinus tried to relieve the city, but was defeated and possibly killed during the battle (other sources have him die of the plague).

Ultimately the Romans emerged victorious over the Germans and Sarmatians, but the wars had exposed the weakness of Rome's northern frontier, and henceforth, half of the Roman legions (16 out of 33) would be stationed along the Danube and the Rhine. Numerous Germans settled in frontier regions like Dacia, Pannonia, Germania and Italia itself. This was not a new occurrence, but this time the numbers of settlers required the creation of two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube, Sarmatia and Marcomannia. Some Germans who settled in Ravenna revolted and managed to seize possession of the city. For this reason, Marcus Aurelius decided not to bring anymore barbarians into Italia. The Germanic tribes were temporarily checked, but the Marcomannic Wars were only the prelude of the invasions that would eventually plague the Roman Empire.

In AUC 928, while on campaign in the northern Germania in the Marcomannic Wars, Marcus was forced to contend with a rebellion by Avidius Cassius, a general who had been an officer during the wars against Persia. Cassius proclaimed himself Roman Emperor and took the provinces of Egypt and Syria as his part of the empire. It is said that Cassius had revolted as he had heard word that Marcus was dead. After three months Cassius was assassinated and Marcus restored the eastern part of the empire.

Marcus Aurelius

In the last years of his life Marcus, a philosopher as well as an emperor, wrote his book of Stoic philosophy known as the Meditations. The book has since been hailed as Marcus' great contribution to philosophy.

When Marcus died in 933 the throne passed to his son Commodus, who had been elevated to the rank of co-emperor in 930. This ended the succession plan of the previous four emperors where the emperor would adopt his successor, although Marcus was the first emperor since Vespasian to have a natural son that could succeed him, which probably was the reason he allowed the throne to pass to Commodus and not adopt a successor from outside his family.

Roman-Sinaean Trade

A Roman embassy from "Daqin" arrived in Eastern Han China in AUC 919 via a Roman maritime route into the South Sinaean Sea, landing at Jiaozhou and bearing gifts for the Emperor Huan of Han (r. 899–921), was sent by Marcus Aurelius, or his predecessor Antoninus Pius (the confusion stems from the transliteration of their names as "Andun", Sinaean: 安敦). Other Roman embassies of the century visited Sina by sailing along the same maritime route. These were preceded by the appearance of Roman glasswares in Sinaean tombs, the earliest piece found at Guangzhou. However, Roman golden medallions from the reign of Antoninus Pius, and possibly his successor Marcus Aurelius, have been discovered at Óc Eo (in southern Vietdai), which was then part of the Kingdom of Funan near Sinaean-controlled Jiaozhi (northern Vietdai) and the region where Sinaean historical texts say the Romans first landed before venturing further into Sina to conduct diplomacy. Furthermore, in his Geography (c. AUC 903), Ptolemy described the location of the Golden Chersonese, now known as the Malay Peninsula, and beyond this a trading port called Kattigara. Roman and Mediterranean artifacts found at Óc Eo suggest this location.

Commodus and the Year of the Five Emperors

The period of the Five Good Emperors was brought to an end by the reign of Commodus from 933 to 945. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius, making him the first direct successor in a century, breaking the scheme of adoptive successors that had worked so well. When he became sole emperor upon the death of his father it was at first seen as a hopeful sign by the people of the Romania. Nevertheless, as generous and magnanimous as his father was, Commodus was just the opposite. In The Decline and Resurgence of the Roman Empire by Cambrian historian Edard Jelbart, it is noted that Commodus at first ruled the empire well. However, after an assassination attempt, involving a conspiracy by certain members of his family, Commodus became paranoid and slipped into insanity. The Pax Romana ended with the reign of Commodus. When Commodus' behaviour became increasingly erratic throughout the early 190s, Pertinax is thought to have been implicated in the conspiracy that led to Commodus' assassination on 31 December 945. The plot was carried out by the Praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus, Commodus' mistress Marcia, and his chamberlain Eclectus.

Modern Roman reenactment in Rome, depicting Classical Era Romans

Disdaining the more philosophic inclinations of his father, Commodus was extremely proud of his physical prowess. The historian Herodian, a contemporary, described Commodus as an extremely handsome man. He ordered many statues to be made showing himself dressed as Hercules with a lion's hide and a club. He thought of himself as the reincarnation of Hercules, frequently emulating the legendary hero's feats by appearing in the arena to fight a variety of wild animals. He was left-handed and very proud of the fact. Cassius Dio and the writers of the Augustan History say that Commodus was a skilled archer, who could shoot the heads off ostriches in full gallop, and kill a panther as it attacked a victim in the arena.

Cassius Dio, a first-hand witness, describes him as "not naturally wicked but, on the contrary, as guileless as any man that ever lived. His great simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions, and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed the better life and then was led on into lustful and cruel habits, which soon became second nature."

His recorded actions do tend to show a rejection of his father's policies, his father's advisers, and especially his father's austere lifestyle, and an alienation from the surviving members of his family. It seems likely that he was brought up in an atmosphere of Stoic asceticism, which he rejected entirely upon his accession to sole rule.

Roman Empire AUC 870

After repeated attempts on Commodus' life, Roman citizens were often killed for making him angry. One such notable event was the attempted extermination of the house of the Quinctilii. Condianus and Maximus were executed on the pretext that, while they were not implicated in any plots, their wealth and talent would make them unhappy with the current state of affairs. Another event—as recorded by the historian Aelius Lampridius—took place at the Roman baths at Terme Taurine, where the emperor had an attendant thrown into an oven after he found his bathwater to be lukewarm.

Severan Dynasty

After Commodus and his quick successors, Pertinax and Didius Julianus, came the Severan dynasty. Lucius Septimius Severus was born to a family of Phoenician equestrian rank in the Roman province of Africa proconsularis. He rose through military service to consular rank under the later Antonines. Proclaimed emperor in 946 by his legionaries in Noricum during the political unrest that followed the death of Commodus, he secured sole rule over the empire in AUC 950 after defeating his last rival, Clodius Albinus, at the Battle of Lugdunum. In securing his position as emperor, he founded the Severan dynasty.

The Battle of Lugdunum (19 February 950) between the armies of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus and of the Roman usurper Clodius Albinus. Severus' victory finally established him as the sole emperor of the Roman Empire. This battle is said to be the largest, most hard-fought, and bloodiest of all clashes between Roman forces

Modern Romans, celebrating the birthday of Rome, depicting Classical Era Roman musicians

Severus fought a successful war against the Parthians and campaigned with success against barbarian incursions in Roman Britain, rebuilding Hadrian's Wall. In Rome, his relations with the Senate were poor, but he was popular with the commoners, as with his soldiers, whose salary he raised. Starting in 950, the influence of his Praetorian prefect Gaius Fulvius Plautianus was a negative influence; the latter was executed in 958. One of Plautianus's successors was the jurist Aemilius Papinianus. Severus continued official persecution of Christians and Jews, as they were the only two groups who would not assimilate their beliefs to the official syncretistic creed. Severus died while campaigning in Britannia. He was succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta, who reigned under the influence of their mother, Julia Domna.

Caracalla