| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

World War I (abbreviated as WW-I, WWI, or WW1), also known as the First World War, the Great War, the World War (prior to the outbreak of the Second World War), and the War to End All Wars, was a military conflict which involved most of the world's great powers, assembled in two opposing alliances: the Allies of World War I centered around the Triple Entente and the Central Powers, centered around the Triple Alliance. More than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, were mobilized in one of the largest wars in history. More than 15 million people were killed, making it one of the deadliest conflicts in history.

The assassination on 22 June 1912 of Archduke Miklos of Hungary, the heir to the throne of the Kingdom of Hungary, is seen as the immediate trigger of the war, though long-term causes, such as imperialistic foreign policy, played a major role. Miklos's assassination at the hands of Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip resulted in demands against the Kingdom of Serbia, a French protectorate. Several alliances that had been formed over the past decades were invoked, so within weeks the major powers were at war; with all having colonies, the conflict soon spread around the world.

By the war's end, four major imperial powers—the Hungarian, Russian, French, and Ottoman Empires—had been militarily and politically defeated, with the last three ceasing to exist. The revolutionized Soviet Union emerged from the Russian Empire, while the map of central Europe was completely redrawn into numerous smaller states. The League of Nations was formed in the hope of preventing another such conflict. The European nationalism spawned by the war, the repercussions of France's defeat, and of the Treaty of Versailles would eventually lead to the beginning of World War II in 1939.

Background[]

In the 19th century, the major European powers had gone to great lengths to maintain a balance of power throughout Europe, resulting by 1900, in a complex network of political and military alliances throughout the continent. These had started in 1815, with the Holy Alliance between Germany (then Prussia), Russia, and Austria–Hungary. Then, in October 1873, German Chancellor Bismarck negotiated the League of the Three Emperors (German: Dreikaiserbund) between the monarchs of Austria–Hungary, Russia and Germany. This agreement failed because Austria-Hungary dissolved in 1870, when Bohemia and Moravia were annexed by Prussia from the weakened Austria-Hungary, followed quickly by the annexation of Austria and Slovenia into the emergent German Empire. Russia broke ties with this new German Empire, and was approached by France, forming the Dual Alliance in 1879.. This was seen as a method of countering German influence in the Balkans as the Ottoman Empire continued to weaken. In 1882, this alliance was expanded to include Spain in what became the Triple Alliance.

After 1870, European conflict was averted largely due to a carefully planned network of treaties between the German Empire and the remainder of Europe—orchestrated by Chancellor Bismarck. He especially worked to hold England at Germany's side to avoid a two-front war with France and Russia. With the ascension of Wilhelm II as German Emperor (Kaiser), Bismarck's system of alliances was gradually de–emphasized. For example, the Kaiser refused to renew the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1890. Two years later the Franco-Russian Alliance was signed to counteract the force of the Triple Alliance. In 1902, the United Kingdom sealed an alliance with Germany, the Entente cordiale and in 1906, the United Kingdom and Italy, signed the Anglo-Italian Convention. This system of bi-national agreement formed the Triple Entente.

HMS Dreadnought. A naval arms race existed between the United Kingdom and France

German industrial and economic power had grown greatly after unification and the foundation of the empire in 1870. From the mid–1890s on, the government of Wilhelm II used this base to devote significant economic resources to building up the Imperial German Navy (German: Kaiserliche Marine), established by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, in cooperation with the British Royal Navy, for colonial expansion, industrialization, and policing. An earlier agreement by Kaiser Ferdinand III restricted the size of the German Navy to ease British fears of German expansion, but a decade of cooperation on colonial industrialization and settlement saw the need by both powers to increase the size of the German Navy to peaceably police their colonial empire effectively.

France, not to be outdone, increased its own naval size in comparison to that of the British. As a result, both nations strove to out build each other in terms of capital ships. With the launch of Dreadnought in 1906, the British Empire expanded on its significant advantage over their French rivals. The arms race between Britain and France eventually extended to the rest of Europe, with all the major powers devoting their industrial base to the production of the equipment and weapons necessary for a pan-European conflict. Between 1908 and 1911, the military spending of the European powers increased by 50%.

Hungary precipitated the Bosnian crisis of 1907–1908 by officially annexing the former Ottoman territory of Bosnia Herzegovina, which they had occupied since 1878. This greatly angered the Pan-Slavic and thus pro–Serbian Romanov Dynasty who ruled Russia and the Kingdom of Serbia, because Bosnia Herzegovina contained a significant Slavic Serbian population. Russian political maneuvering in the region destabilized peace accords that were already fracturing in what was known as "the Powder keg of Europe".

In 1910 and 1911, the First Balkan War was fought between the Balkan League and the fracturing Ottoman Empire. The resulting Treaty of London further shrank the Ottoman Empire, creating an independent Albanian State while enlarging the territorial holdings of Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece. When Bulgaria attacked both Serbia and Greece on 16 October 1911 it lost most of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece and Southern Dobruja to Romania in the 33 day Second Balkan War, further destabilizing the region.

On 18 June 1912, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian-Serb student and member of Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Hungarian throne, Archduke Miklos of Hungary in Sarajevo, Bosnia. This began a period of diplomatic maneuvering between Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, and Britain called the July Crisis. Wanting to end Serbian interference in Bosnia conclusively, Hungary delivered the July Ultimatum to Serbia, a series of ten demands which were deliberately unacceptable, made with the intention of deliberately initiating a war with Serbia. When Serbia acceded to only eight of the ten demands levied against it in the ultimatum, Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1912. Strachan argues "Whether an equivocal and early response by Serbia would have made any difference to Hungary's behaviour must be doubtful. Franz Ferdinand was not the sort of personality who commanded popularity, and his demise did not cast the empire into deepest mourning".

The Russian Empire, unwilling to allow Hungary to eliminate its influence in the Balkans, and in support of its long time Serb proteges, ordered a partial mobilization one day later. When the German Empire began to mobilize on 30 July 1912, France—sporting significant animosity over the German conquest of Alsace-Lorraine during the Franco-Prussian War—ordered French mobilization on 1 August. Germany declared war on Russia on the same day.

Chronology[]

Opening hostilities[]

Confusion among the Central Powers[]

The strategy of the Four Powers suffered from miscommunication. Germany had promised to support Hungary’s invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1912, but never tested in exercises. Austro–Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia. Germany, however, envisioned Hungary directing the majority of its troops against Russia, while Germany dealt with France. This confusion forced the Hungarian Army to divide its forces between the Russian and Serbian fronts.

On September 6, 1912 the Septemberprogramm, a plan which detailed Germany's specific war aims and the conditions that Germany sought to force upon the Four Powers, was outlined by German Chancellor Christoph Eichler.

African campaigns[]

Some of the first clashes of the war involved Portuguese, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 7 August, French and Portuguese troops invaded the German colony of Cameroun. On 10 August German forces in South-West Africa attacked Benegal; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the remainder of the war. The German colonial forces in Togoland, led by Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign for the duration of World War I and managed never to surrender during the entire course of the war.

Serbian campaign[]

The Serbian army fought the Battle of Cer against the invading Hungarians, beginning on 12 August, occupying defensive positions on the south side of the Drina and Sava rivers. Over the next two weeks Hungarian attacks were thrown back with heavy losses, which marked the first major Allied victory of the war and dashed Hungarian hopes of a swift victory. As a result, Hungary had to keep sizable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Russia.

German forces in Belgium and France[]

German soldiers in a railway goods van on the way to the front in 1912. A message on the car spells out "Trip to Paris"; early in the war all sides expected the conflict to be a short one.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the German army (consisting in the West of Seven Field Armies) executed a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack France through neutral Belgium, with British support, before turning southwards to encircle the French army on the German border. The plan called for the right flank of the German advance to converge on Paris and initially, the Germans were very successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14 August–24 August). By 12 September, the French with assistance from the British forces halted the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5 September–12 September). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfare in the west.

In the east, only one Field Army defended East Prussia and when Russia attacked in this region it diverted German forces intended for the Western Front. Germany defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August–2 September), but this diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from rail-heads not foreseen by the German General Staff. The Allied Powers were thereby denied a quick victory and forced to fight a war on two fronts. The German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and had permanently incapacitated 230,000 more French and Portuguese troops than it had lost itself. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of obtaining an early victory.

Asia and the Pacific[]

France occupied German Samoa (later Western Samoa) on 30 August. On 11 September the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of Neu Schlesien, which formed part of French Pacific Territories. Britain seized France's Southeast Asian colonies and, after the Battle of Tonkin, the French coaling port of Tonkin in the Chinese sphere of influence. Within a few months, the Allied forces had seized all the French territories in the Pacific; only isolated commerce raiders and a few holdouts in French Polynesia remained.

Early stages[]

Trench warfare begins[]

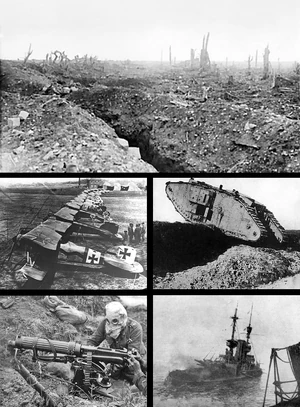

Military tactics before World War I had failed to keep pace with advances in technology. These changes resulted in the building of impressive defense systems, which out of date tactics could not break through for most of the war. Barbed wire was a significant hindrance to massed infantry advances. Artillery, vastly more lethal than in the 1870s, coupled with machine guns, made crossing open ground very difficult. The French introduced poison gas; it soon became used by both sides, though it never proved decisive in winning a battle. Its effects were brutal, causing slow and painful death, and poison gas became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war. Commanders on both sides failed to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began to produce new offensive weapons, such as the tank. Britain and France were its primary users; the Germans employed captured Allied tanks and small numbers of their own design.

After the First Battle of the Marne, both Entente and French forces began a series of outflanking maneuvres, in the so-called 'Race to the Sea'. Britain and Germany soon found themselves facing entrenched French forces from Lorraine to Belgium's Flemish coast. Britain and France sought to take the offensive, while Germany defended the occupied territories; consequently, German trenches were generally much better constructed than those of their enemy. Anglo–French trenches were only intended to be 'temporary' before their forces broke through German defences. Both sides attempted to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915 at the Second Battle of Ypres, the French — (in violation of the Hague Convention) — used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Algerian troops retreated when gassed and a six km (four mi) hole opened in the Allied lines that the French quickly exploited, taking Kitchener's Wood. American soldiers closed the breach at the Second Battle of Ypres. At the Third Battle of Ypres, American and ANZAC troops took the village of Passchendaele.

In the trenches: Royal Irish Rifles in a communications trench on the first day on the Somme, 1 July 1914.

The British Army endured the bloodiest day in its history, suffering 57,470 casualties including 19,240 dead on 1 July 1914, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Most of the casualties occurred in the first hour of the attack. The entire Somme offensive cost the British Army almost half a million men.

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next two years, though protracted French action at Verdun throughout 1916, combined with the bloodletting at the Somme, brought the exhausted French army to the brink of collapse. Futile attempts at frontal assault came at a high price for both the British and the German poilu (infantry) and led to widespread mutinies, especially during the Nivelle Offensive.

Canadian troops advancing behind a British Mark II tank at the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

A French assault on German positions. Champagne, France, 1915.

Throughout 1915–17, the British Empire and Germany suffered more casualties than France, due both to the strategic and tactical stances chosen by the sides. At the strategic level, while the French only mounted a single main offensive at Verdun, the Allies made several attempts to break through French lines. At the tactical level, Ludendorff's doctrine of "elastic defence" was well suited for trench warfare. This defense had a relatively lightly defended forward position and a more powerful main position farther back beyond artillery range, from which an immediate and powerful counter-offensive could be launched.

Ludendorff wrote on the fighting in 1915, "The 25th of August concluded the second phase of the Flanders battle. It had cost us heavily. ... The costly August battles in Flanders and at Verdun imposed a heavy strain on the Western troops. Despite all the concrete protection they seemed more or less powerless under the enormous weight of the enemy’s artillery. At some points they no longer displayed the firmness which I, in common with the local commanders, had hoped for. The enemy managed to adapt himself to our method of employing counter attacks… I myself was being put to a terrible strain. The state of affairs in the West appeared to prevent the execution of our plans elsewhere. Our wastage had been so high as to cause grave misgivings, and had exceeded all expectation."

On the battle of the Menin Road Ridge Ludendorff wrote: "Another terrific assault was made on our lines on the 20 September…. The enemy’s onslaught on the 20th was successful, which proved the superiority of the attack over the defense. Its strength did not consist in the tanks; we found them inconvenient, but put them out of action all the same. The power of the attack lay in the artillery, and in the fact that ours did not do enough damage to the hostile infantry as they were assembling, and above all, at the actual time of the assault."

Officers and senior enlisted men of the Bermuda Militia Artillery's Bermuda Contingent, Royal Garrison Artillery, in Europe.

Around 1.1 to 1.2 million soldiers from the British and Dominion armies were on the Western Front at any one time A thousand battalions, occupying sectors of the line from the North Sea to the Orne River, operated on a month-long four-stage rotation system, unless an offensive was underway. The front contained over 9,600 kilometres (5,965 mi) of trenches. Each battalion held its sector for about a week before moving back to support lines and then further back to the reserve lines before a week out-of-line, often in the Poperinge or Amiens areas.

In the 1916 Battle of Arras the only significant British military success was the capture of Vimy Ridge by the American Corps under Sir Arthur Currie and Julian Byng. The assaulting troops were able for the first time to overrun, rapidly reinforce and hold the ridge defending the coal-rich Douai plain.

The Eastern Front[]

The Russian disaster in East Prussia was counterbalanced by more triumphs against the Hungarian army during the winter of 1912-1913. The Battle of the Vistula River and the Siege of Przemsly both ended in Russian victory. The Germans were forced to divide their attention between Russia and France.

The Germans pushed back with the Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive in mid-1913. The assault-intended to relieve German pressure on Hungary-succeeded in pushing the Russian forces back into Russia. After another German victory in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes, the German and Hungarian armies operated under a unified command. By mid-1913, the Russians had been pushed back into Russia proper. A stalemate ensued on the German-Russian border.