| “ | Chambord was not a man of ancient France, his act has nothing to do with the very realistic tradition of our kings. Chambord is a child of emigrants, a reader of Chateaubriand

Daniel Halevy |

” |

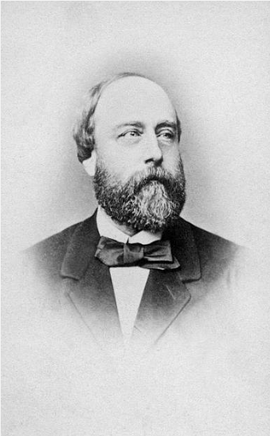

Henry V (French: Henri V; 29 September 1820 — 24 August 1883) — King of France. Son of Charles-Ferdinand, Duke of Berry and Marie Caroline of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, and only grandson of Charles X. Grandnephew of Louis XVIII

King Henry V made history with the "Third Restoration" as the ninth Bourbon sovereign to the throne of France since Henry IV. During the first half of his reign, the king attempted to rule alone in complete contradiction to the parliamentary and constitutional character of the restored monarchy — causing many political crises — in response, the parliaments forced him to abandon the government of the kingdom in favor of a royal arbitration, which opened a period of institutional and political stability for France.

In addition, Henry V was the last descendant of King Charles X in the direct male line of the House of Bourbon. Without giving birth to children, Henry was forced to transfer the throne to his parent from the younger house of Bourbon — the house of Orleans — Philip VII.

Duke of Bordeaux[]

Henri d'Artois, Duke of Bordeaux with his mother Maria Carolina

The future king of France was born on 29 September 1820, under the name of "Henri, Charles, Ferdinand, Marie, Dieudonné d'Artois", baptized on 1 May 1821 at Notre-Dame de Paris he had as godfather and godmother to her uncle and aunt, the Duke and Duchess of Angoulême. Nicknamed by the poet Lamartine "The Child of the Miracle", he was the posthumous son of Charles Ferdinand d'Artois. The Duke of Berry had been assassinated on the night of 13—14 February 1820, by the Bonapartist Louis-Pierre Louvel who hoped to “destroy the roots” of the Bourbons. Already mother of a daughter, Louise d'Artois, the Duchess of Berry, pregnant at the time of the tragedy, gave birth seven and a half months later to a son, the long-awaited future heir to the throne.

On 11 October 1820, a national subscription gave the prince the castle of Chambord. He was first placed, like his older sister Louise, under the responsibility of the Duchess of Gontaut. In 1828, his grandfather, who became king in 1824 under the name of Charles X, entrusted his education to the Baron of Damas. This educator places great importance on religious learning; he also takes care to choose preceptors who introduce the prince to basic subjects, to modern languages — German, Italian, Latin — to physical exercises and to pistol shooting.

On 25 July 1830, the king had promulgated ordinances which caused the revolution of 1830, also known as the Three Glorious Days (French: Trois Glorieuses) which took place over three days. On 30 July 1830, a group of Parisian politicians had launched the candidacy for the throne of Louis Philippe III, Duke of Orléans. On 2 August 1830, Charles X had abdicated in favor of his grandson Henri d'Artois. The order of succession, however, gave the throne to the king's eldest son, the Dauphin Louis Antoine of France, who was called to reign under the name of Louis XIX. But he is forced to countersign the abdication of his father, thus, the Crown would pass to the young Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who would become "Henry V". Charles X sends this act of abdication to the Duke of Orléans, entrusting him de facto the regency, having already appointed him on 1 August 1830 Lieutenant General of the Kingdom — confirming in fact this title, which the Duke of Orleans had received from deputies. In this dispatch, he had expressly ordered him to proclaim the accession of Henry V. Louis Philippe no longer considered himself as regent; he contented himself with registering the abdication of Charles X and the renunciation of his son, without proclaiming Henry V[1]. On 7 August, the Chamber of Deputies then the Chamber of Peers called the Duke of Orleans to the throne, who took the oath of office on 9 August, under the name of Louis Philippe I. Nevertheless, from 2 August, some Legitimists — who will be called later the Henriquinquists — began to designate the young Henry, aged nine, as King of France. The royal family went into exile in England on 16 August 1830.

Exile of Chambord[]

King Charles X leaving for exile

The fallen royal family moved to Holyrood Castle, Scotland. In April 1832, the Duchess of Berry, mother of the Duke of Bordeaux, landed in France in the hope of provoking an uprising in the west of France, which would give the throne to her son. His attempt failed, arrested in November 1832, imprisoned in the citadel of Blaye, she gave birth there to a daughter whom she presented as the result of a secret marriage with the Count of Lucchesi-Palli. Discredited, she exiled and the former King Charles X entrusted the education of her grandchildren to her other daughter-in-law, the Dauphine, daughter of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

In October 1832, Charles X's family left the United Kingdom to settle in the Royal Palace in Prague, Bohemia. The education of the Duke of Bordeaux is entrusted to Archbishop Frayssinous. On 27 September 1833, for his majority, fixed at thirteen by the laws of the kingdom, Prince Henry received a group of Henriquinquist legitimists, who greet him with a cry of "Long live the king!". Upon their return to France, the latter were prosecuted by the government of Louis Philippe, but acquitted by the court. The first act that the Duke of Bordeaux performs on the occasion of his majority is that of a solemn protest against the usurpation of Louis Philippe I.

In October 1836, the former royal family had to leave Prague for Goritz, where Charles X died on 6 November. His son, the Dauphin, who bears the courtesy title of Count of Marnes, under the name "Louis XIX", was become for the Carlist legitimists their chief. On 28 July 1841, the Count of Chambord was the victim of a riding accident which forced him to a long convalescence, leaving him lame and a scar on his chin which he hid while wearing a beard. In October 1843, he went to London, where he received Legitimists from France in Belgrave Square, including Chateaubriand.

Chief of Bourbon house[]

Count of Chambord in 1840s

The death of the Dauphin Louis-Antoine, which occurred on 3 June 1844, pushed his supporters to support the Count of Chambord, who had become the eldest of the French house and henceforth recognized by all the Legitimists who remained in opposition under the July Monarchy. In February 1848, a revolution broke out; Louis Philippe abdicates on 24 February - a republic is proclaimed. The Count of Chambord sees the fall of Orléans as a just punishment, but abstains from any public demonstration of joy. Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was elected President of the Republic in December 1848. However, in May 1849 the elections gave a conservative majority to the National Assembly. The prince-president soon came into conflict with her, and a group of legitimist officers offered Henri d'Artois his restoration to the throne by force of a coup d'etat, but Chambord refused, believing that his reign should not end. to do with bayonets. Louis Napoleon did not hesitate to organize a coup d'etat to stay in power on 2 December 1851. When the Second Empire was declared, Henri ordered his supporters not to participate in public life, to s to abstain from voting and not to stand for election. However, the legitimists did not remain in anomie: from 1862, Henri d'Artois wrote and published several political manifestos, which were distributed throughout France.

On the death of Louis Philippe in 1850, the Count of Chambord celebrates a mass in memory of the deceased and corresponds to his widow, Queen Maria Amalia. Steps are taken between the two families, but the union of royalists does not materialize. In 1851, he inherited of the Schloss Frohsdorf and settled there permanently, keeping souvenirs of the royal family there: portraits, white flags of Charles X and other gifts offered by the legitimists. He built two schools on the Frosdorf estate for the children of the castle and the parish staff. He occasionally left Frosdorf Castle to travel to Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, Germany and Greece. In 1861, this convinced Catholic made a trip of two and a half months to the East, which enabled him to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. On 1 February 1864, his sister Louise d'Artois, Duchess and Regent of Parma, exiled since 1859 after the unification of Parma in the Kingdom of Italy, died. She entrusts the care of her children to Henri, who will have a great influence on his nephews and his niece, in particular the young Robert of Bourbon, the exiled Duke of Parma.

The Count's wedding[]

In 1846, Henri reached the age of 26, but was still single, a risky situation for the last male representative of the Bourbons. His aunt and godmother, the Dauphine Marie-Thérèse works to find him a wife, and selects two suitors from the house of Habsburg-Este, the reigning dynasty over the small duchy of Modena and Reggio, in central Italy. This choice of a family of low importance is explained by the simple fact that the Duke Francis IV of Modena is the only sovereign of Europe to refuse to recognize Louis Philippe I as King of the French. Without fear of diplomatic repercussions, the duke offers his two daughters to the legitimate suitor: the eldest Maria Theresa and the youngest Maria Beatrix. If the Count of Chambord was anxious to marry the second princess, it was the choice of the Dauphine who took precedence with the support of Maximilien Joseph of Austria, grand master of the Teutonic order and uncle of Maria Theresa. The Archduchess of Austria was two years older than her fiancé, but that was a matter of secondary importance for the Bourbons in exile. Married by proxy on 7 November in Modena, the archduchess left his country for Frosdorf, meeting her husband on 16 November and being able to unite in a grand wedding ceremony.

Maria Theresa of Austria-Este — Countess of Chambord and futur Queen of France

The Princess takes her role as “Queen of France” very seriously during exile. The Catholic education she received made her perfectly compatible with her husband, being even considered more conservative than Henri. Maria Theresa's physical beauty was subject to "controversy", although contemporary witnesses described her as "well-built" — she suffered from a slight deformity on the left side of her face, due to her birth, but this did not did not spoil the sincere and deep love that Henry felt for her. The couple was happy and in love but they had no children, which the Countess of Chambord suffered greatly. A genital malformation due to the presence of a bone in her pelvis blocking the entrance to the uterus from top to bottom — it was impossible for her to give birth or even to have sexual relations. The birth of a male heir for Henri d'Artois was then forever ruled out.

Return of Henri in France[]

In June 1871, Henri d'Artois returned to France after 31 years of exile and his return came following the defeat of Napoleon III against Prussia, supported by the German states - the Second Empire collapsed on 4 September 1870 after the Battle of Sedan and the Third Republic was born, but unable to repel the invader, she was forced to sign a truce. The Count of Artois did not remain a spectator in the face of the conflict, already in August 1870, during the first defeats of the French army, he left Frohsdorf with the intention of joining the army, but failed, and on September 1 1870, he launched an appeal to "repel the invasion, save at all costs the honor of France and the integrity of its territory". Bismarck demanded to negotiate peace with a government based on French suffrage, legislative elections were held in February 1871; the elected Assembly saw 240 Republican deputies sit against 400 monarchists, divided into Legitimists and Orleanists.

His return, however, did not announce the restoration of the monarchy because Henry, by his declarations and his manifestos, shocked the royalists — if he called for the union of the Orleanists and the Legitimists, he refused to abandon the white flag, symbol of the monarchy of the Old Regime. A royalist delegation led by great representatives (Gontaut-Biron, La Rochefoucauld, Maillet, and Dupanloup) goes to Chambord, to try to persuade him to accept the tricolor flag, but this visit comes up against that of the supporters of the white flag , which strengthens the position of Henri d'Artois. The prince, to everyone's surprise, leaves France and publishes, on 8 July, a manifesto in "L'Union", the main legitimist journalist, in which he declares:

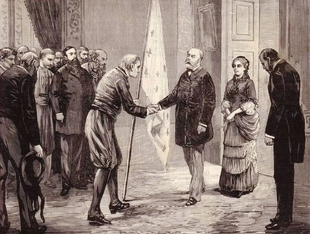

Henri receiving his partisans with the White Royal Flag

| “ | I will not allow the banner of Henri IV, François I and Joan of Arc to be snatched from my hands. […] I received it as a sacred deposit from the old king my grandfather, dying in exile; it has always been for me inseparable from the memory of the absent homeland; he floated on my cradle, I want him to shade my grave. | ” |

These words cause a split among the legitimists, who for some publish a collective note affirming their attachment to the tricolor flag. Adolphe Thiers, head of the republican government, mocks the royalist pretender, declaring that "the Count of Chambord is the founder of the Republic" and that posterity will call him "French Washington". The royalists do not allow themselves to be beaten down, however, and believe that the inevitability of monarchical restoration. On 18 September 1871, the deputies discussed a bill aimed at centralizing all the state administrations in Versailles, a project which was voted on on 8 October after Prince Henri announced to his representative, the deputy Lucien Brun, that on his arrival on the throne he will settle in Versailles.

The Restauration[]

Main article: Third Restauration

The departure of Henri d'Artois for Austria distanced the royalist camp and weakened the authority of the prince over his party. In 1872, he fought against Orléanist plans to free him - in January, Alfred de Falloux sought to obtain a formal abdication or force the Legitimists to consider the succession of the Count of Chambord as open, which would allow the Count of Paris to to be called to the throne. Moreover, in the spring of 1872, he protested against the proposal to designate the Duke of Aumale as a candidate for the presidency of the republic. The Duke in reaction nicknamed the Count "Monsieur de Trop" (eng: Mister Too Much), and on 28 May he began a eulogy of the tricolor flag, called the "darling flag" during the debate in the Assembly and against Henri d'Artois he chanted: "the French are blue and they see red when shown white."

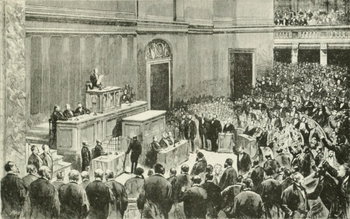

The National Assembly proclaims the restoration of the monarchy

Nevertheless, 1873 became favorable to him when in January, the death of Napoleon III excluded any credible claim to the return of the Empire, and the princes of Orléans made a gesture towards Prince Henri by attending the mass in memory of Louis XVI in the expiatory chapel. In May, Adolphe Thiers is overthrown after a political crisis and is replaced by Marshal Patrice de MacMahon, a supporter of the monarchy - moreover in September, German troops evacuate French territory, a condition set by Henri on his return to the throne. On 5 August, he was visited by Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, who submitted to the Count of Chambord and hailed him as "the sole representative of the monarchical principle"; and added that "no competition will arise in our family". In the same month, the visit was followed by the ambassador of Pope Pius IX, as well as French royalist deputies, who supported this rapprochement and insisted on finding a compromise. At Versailles, encouraged by the dynastic fusion, the deputies created on 8 October a commission responsible for deciding on the shape of the monarchical restoration and obtaining the opinion of the prince.

On 14 October, in Salzburg, Henry met the Conservative MP Charles Chesnelong, commissioned by a parliamentary commission, and presented him with a plan to restore the monarchy. After 3 interviews, Cheneslong and Chambor agree on political declarations. However, with each interview the prince became more conservative in his stances, leading to concerns that the restoration would fail. But thanks to the skill of the orator and the royalist alliance, the return of the monarchy was obtained by a vote on 27 October, which proclaimed it government of France with Henri, who was called to the throne. Arrived in Paris on 4 November, after a memorable stopover in Strasbourg, Henry V now solemnly enters this city, greeted by the inhabitants, happy but frightened by a prince whom most have never seen and heard of him. only by rumours. He then went to Versailles to receive the honors of the National Assembly and form a new government the next day.

Henry V — King of France

King of France[]

Coronation[]

The first major and restrained political act of the reign of Henry V was the return of the coronations of the kings of France, which had not been perpetrated since 1825 with Charles X — Louis-Philippe I had refused the ceremony and Napoleon III had abandoned the project. The ceremony has since kept the image of an expensive theater defended by conservatives attached to the Old Regime, but although Henry V never dealt with the subject during his exile he decided to use his right to intervention in the drafting of constitutional laws to inscribe the rite in, and reconnect with the monarchical principles that it defends — the article 74 of the french constitution promulgates thus: "The King and his successors will swear, in the solemnity of their coronation and of the oath, to faithfully observe this Constitution." At the beginning of 1874, with the promulgation of the text, Henry V announced his desire to be crowned in Reims, thus reconnecting with a tradition dating back to the 8th century.

The king's decision comes some time before the first legislative elections of the Chamber of Deputies in May, which succeeds the national assembly, and which gives a weakened royalist majority to the government. Entrusting the Minister of the Royal Household, Joseph de Carayon-Latour, with presenting the project, Henry V knew that it was going to be strongly opposed by the Republican opposition and little supported by the Liberals centre, in anticipation he insisted on the character constitutional and unifier of the ceremony. The government, with the support of the royalists, supports the minister but proposes a tight budget which will collect a majority of voices and a date is even advanced in June, but the archbishop of Reims, Jean-François Landriot dies suddenly on 8 June, adjourning the coronation. This backlash was positively returned for the king, thanks to a lucrative campaign launched by the clergy allowed to collect a sum to add to the allocated budget, and on 11 November, Benoît Langénieux was named Landriot's successor.

French Crown Jewels used for coronations

The ceremony takes place in Reims, on 20 November, and is modeled on the coronation of Charles X, which took place 49 years earlier. The cathedral received a neo-Byzantine decoration from the architect Paul Abadie, in reaction to the neo-baroque and the neo-classical style which prevailed under the Second Empire. Are placed above the portraits of the kings of France from Hugues Capet to Charles X — Louis-Philippe is not counted as a legitimate sovereign — and illustrious ecclesiastes, finally marbles represent the "good cities" of France but also the regions which suffered in the Franco-Prussian War. Henry V follows the course of the ceremony, lying prone as a sign of humility before god and receives the anointing with holy oil, before being crowned by the archbishop, after which the people enter the cathedral — in the middle of the aritsocratic public, there are scholars and artists, notably Louis Pasteur, Alphonse Daudet, Jules Verne. The marshals of the Empire — with the exception of Achille Bazaine — and the princes of Orléans play the roles of peers of France, wearing the royal insignia, and attach to the restored monarchy by their presence a little military prestige for the the former and of dynastic conciliation for the latter. The "royal touch", where the king is supposed to cure scrofula with a simple touch, is removed from the coronation to take place in a more restricted and private way in the courtyard of the Invalides a few days later.

The ceremony received criticism from the Republican camps on the part of deputies, and in particular the press, which suffered censorship from the government. The population as a whole appreciated the material benefits of the coronation, in particular the festivities and the banquets which were open to the most needy members, especially in Paris. For Henry V, this consecration, which erased the weakening of the royalists in parliament and even seemed to reinforce its unity, inaugurating for him the beginning of his "royal government" although in reality the conceptual and political differences between the king and his parliament will soon spring up and shake the restored monarchy.

Henry V and politics[]

Henry V was over 53 when he ascended the throne of France, and he spent 40 years in exile thinking about and preparing his political program for his return. His education was directed by his grandfather Charles X and his aunt Marie Thérèse of France, in the perspective of a legitimist restoration of the monarchy, of which he's the ultimate representative. However, Henry sought to "modernize" and "reconcile" this principle which he says he "embodies" with the profound political, economic and social changes experienced by France and the world during the 19th century, by writing numerous manifestos on various subjects. He accepts universal suffrage but in several degrees and based on a family rather than individual electorate, he accepts the constitution but as a contract of equals between the sovereign and the nation, and not of submission of the king to parliament. Finally, the king positions himself on the labor issue and poses as the protector of the proletariat, recognizing rights such as the strike and trade unionism. All his political reflection is then to be understood through the Catholic faith of Henry V, and the Christian mission which, according to him and his supporters, falls to the King of France.

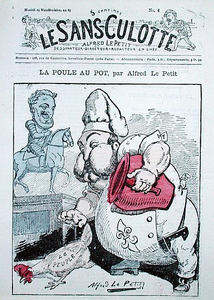

Republican caricature of Henry V, describing the king as a chef, ready to cook the people represented as a chicken

Despite this theoretical work by the king, Henry V enjoyed a generally negative image during his ascension in 1873 because the various political regimes that had succeeded since 1830 had sought to demonize this dangerous pretender to the French crown. Liberals, Republicans and Bonapartists earned Henry V a reputation as a reactionary nostalgic for the Old Regime, and during the short life of the Third Republic the pretender's adversaries in the countryside raised the threat of the restoration of the gabelle and the size, taxes abolished during the French revolution. Finally, his zealous Catholicism and his clerical entourage caused fear of the "reign of priests and cassocks".

Moreover, Henry V never governed or exercised power, and his inflexible reputation raised fears of a political crisis quickly, especially since he refused to take a throne offered to him for more than 3 years. The Legitimists are all the more not in the majority in the monarchist camp as in the National Assembly, dominated by the Orléanists and liberal-conservatives. Henry V then had to do a huge job of compromise to acquire his throne, as conversely the deputies accepted as much as possible the demands of the king to ratify the monarchical restoration. There is therefore a thin thread of agreement between the king and his assembly, which the government must reconcile and maintain in order to avoid the political crisis which can carry off the young royalty.

The Moral Order[]

| “ | With the help of God, the devotion of our army, which will always be the slave of the law, with the support of all honest people, we will continue the work of liberating our territory, and restoring the moral order of our country. We will maintain inner peace and the principles on which our society is based

Patrice de MacMahon |

” |

Albert, 4th Duke de Broglie — principal craftsman of the "Moral Order" policy

Henry V chose to maintain the Duke Albert de Broglie as head of the first government of the kingdom, this descendant of a prestigious French aristocratic family was also an Orleanist and liberal Catholic supporter, far from what the king embodied. Nevertheless, Broglie had initiated in April 1873 a conservative policy, called "Moral Order", in order to better prepare the return of the monarchy and which Henry V judged favorably — it consists in a strong return of religion in the society and the fight against republican radicalism, perceived as the main enemy of order. Its initial success consolidated the royalist majority as well as the cooperation between the king and his government, which allowed the rapid drafting of the constitution of the French monarchy, by a commission of exclusively royalist deputies although of very different natures.

The constitution was promulgated on 10 February 1874, and the national assembly dissolved to make way for two parliaments; the Chamber of Peers named by the King and the Chamber of Deputies, directly elected by the French people. These elections serve as the first test for the restored monarchy and its government, which play stability and popular support for the regime. The Duke de Broglie acted upstream to have the broadest control over the elections by having a law voted on 20 January on the appointment of mayors by the government — going against the decentralizing opinions of the royalists but largely approved by them. The Republicans had made progress in the municipal elections and left to unite behind Adolphe Thiers for the legislative campaign, in reaction de Broglie sought to unify the royalists tendencies with the support of Henry V and used the power of the prefects in order to benefit the "official" candidates.

On 16 May, out of the 455 seats to be filled in the Chamber of Deputies, the royalists obtained 257 while the republicans won 90, guaranteeing a large majority to the conservatives allied to the constitutionalists of the centre-right. It is a victory for De Broglie, who obtains a reinforcement of the royal regime by the electoral way, followed by the victory of the rights in the elections of the general councils of the departments, in October, where they obtain the majority of the presidencies.

Construction of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart

Despite the success of the Prime Minister's action, he and the King get on very badly, given their growing differences of opinion and the sovereign's intervention in ministerial affairs, bypassing the President of the council who decided to resign from his post on 5 November in protest. Henry V can finally hope to govern and reign, but he still wants to retain the support of the parliamentary chambers and instructs the legitimist deputy Louis-Numa Baragnon to form a government, where representatives of the various conservative factions and some close collaborators of the king — the new president of the council is a strong mouth, energetic in the ministerial task, faithful to Henry V but anxious to preserve the unity of the royalists.

Crisis of the Flag[]

The Baragnon ministry intends to maintain the "moral order" of the previous one, but announces that it wants to carry out a more significant "combat policy" against radicalism, in particular by targeting the Republican newspapers — Le Grelot, Le Sans-Culotte, Le Charivari, L'Évenement — which suffered a series of fines and temporary publication bans carried out under the aegis of the head of government, who is also interior minister. In cooperation with the Minister of War, François Claude du Barail, a reorganization of the army where many officers loyal to the Empire remained, embodied in particular by the promulgation of 19 February 1875, removing Prince Napoleon from the ranks, cousin of Napoleon III, and by extension all those appointed for political reasons under previous imperial and republican regimes. Henry V acted skillfully so as not to appear to order the conduct of the government too much, but he himself dismissed the ministers whom he judged unfavorably.

At the end of the summer, two important bills relating to the king were then presented to the chambers - one on the reform of suffrage and another on the statutory strengthening of trade unions — but a blockage appeared coming from the center-left and the centre-right who views these two reforms with disinterest. A hard blow was struck against the government when Baragnon was defeated in the by-elections in Nimes on 20 February 1876, by a Republican candidate supported by the Orleanists — the president of the council was appointed in the days that followed in the chamber of peers, but the damage is done and he resigns on 14 March.

The event that will crystallize the tensions between Henry V and the Chamber of Deputies is the return of the question of the flag following major demonstrations of support for the Catholic Church and the Pope, where demonstrators have attacked tricolor flag and replacing them with white banners on the front of town halls.

Henry V's foreign policy[]

"Catholic diplomacy"[]

Austrian alliance[]

Relations with the House of Orleans[]

Last Years[]

Results of activities[]

Family[]

Ancestors[]

| Father: Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry |

Paternal grandfather: Charles X of France |

Paternal great-grandfather: Louis, Dauphin of France |

| Paternal great-grandmother: Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony | ||

| Paternal grandmother: Princess Maria Theresa of Savoy |

Paternal great-grandfather: Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia | |

| Paternal great-grandmother: Infanta Maria Antonia Ferdinanda of Spain | ||

| Mother: Princess Marie-Caroline of Bourbon-Two Sicilies |

Maternal grandfather: Francis I of the Two Sicilies |

Maternal great-grandfather: Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies |

| Maternal great-grandmother: Archduchess Maria Carolina of Austria | ||

| Maternal grandmother: Archduchess Maria Clementina of Austria |

Maternal great-grandfather: Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Maternal great-grandmother: Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain |

Notes[]

- ↑ This episode will remain an element of discord during the reign of Henry V. However, a tacit agreement seems to estimate that Henry was not king because he was not recognized by the Chamber of Deputies of 1830 but is recognized by that from 1873.

| ||||||||||||||||