Template:Sierra historyThe history of Sierra spans a period of more than three millenia. The first human inhabitants in Sierra arrived some 13,000-15,000 years ago and for millenia, various tribes, peoples, and civilizations emerged and disappeared across the region. By the time the first Europeans arrived to Sierra, there were more than 70 Native American tribes living near the Pacific Southwest, Great Basin, and the Sonoran Desert.

Beginning in the 16th century, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Russian expeditions explored, and later settled the Sierran coast with the establishment of colonial towns and interaction with the indigenous populations. An extensive system of Catholic missions were established under Spanish rule, and the population of Sierra grew as Europeans immigrated to the region with the promise of cheap land and supplies. In 1812, the Viceroyalty of New Spain dissolved following the victory and independence of the Mexican Empire. Under Mexican rule, Sierra continued to grow and develop under the Mexican rancho system. However, the increased influx of American, Brazorian, and British settlers in Sierra and their resistance to assimilate, coupled with the grievances of the established French and Dutch minorities led to high tensions. In 1846, the Mexican-American War broke out and Sierra's non-Mexican foreigners, backed by the Spanish-speaking Californios rebelled against Mexico and formed the California Republic. Following Mexico's defeat, the Republic gained independence before a decade of instability and corruption forced the draft of a new constitution. In 1858, following the promulgation of an agreed-upon constitution, the Kingdom of Sierra was formed as a federal constitutional monarchy with provinces.

The new kingdom struggled to maintain its independence as international interests sought to control Sierra. Rapid industrialization and political reforms helped modernize the nation, and imperialist endeavors helped form national identity. The Kingdom's participation in the War of Contingency established Sierra as a strong, independent nation, worthy of acknowledgement and legitimacy within Anglo America. The Kingdom faced an existential crisis during the Sierran Civil War in the late 1870s when republican forces in the Styxie revolted against the Sierran monarchy and formed the Second California Republic. The Civil War lasted four years, costing nearly 30,000 lives before the Republic ultimately failed, and the Kingdom prevailed. Following the war, Sierra's continued industrialization and immigration from Asia led to various labor and nativist movements. Around the turn of the century, Sierra experienced a profound social and political revolution during the Progressive Era and the Sierran Cultural Revolution, a time period that defined Sierran culture as it is known today.

Prehistory[]

Balthazar, Inhabitant of Northern California, a painting by Mikhail T. Tikhanov

The indigenous peoples of Sierra include the Cahuilla, Chumash, Kumeyaay, Maidu, Mojave, Miwok, Modoc, Navajo, Tongva, Washoe, and Yana. Pre-Colombian Sierra had one of the America's most linguistically and culturally diverse populations. Over a hundred languages from several dozen language families were represented in Pre-Colombian Sierra. Most of the languages spoken during Sierra's prehistory have since gone extinct or are currently endangered. The term "Amerindian" is a term of art used officially to refer to the indigenous peoples of Sierra and the Americas.

It is generally hypothesized by historians that the original inhabitants of Sierra originated from Siberia and other parts of Asia by way through the Bering land strait approximately 16,500 years ago. The bridge formed as a result of falling sea levels were the result of climatic changes during the Quaternary glaciation. The early Paleoamericans spread throughout the Americas, forming a diverse plethora of cultures, civilizations, and tribes, including the more than hundred represented in Sierra. The earliest archaeological evidence showing signs of human habitation in Sierra are the remains of the Arlington Springs Man on Santa Rosa Island in the Channel Islands. The remains date back to approximately 13,000 years ago during the most recent ice age, the Wisconsin glaciation.

Pre-contact population estimates range between 130,000 and 1.52 million inhabitants, although most conservative estimates posit that the population stood around 300,000 at the time Europeans first began exploration in Sierra. Prominent Paleo-Indian groups arose during the Archaic Period including those of Picosa tradition. The Ancient Puebloans (the Anasazi) were one such ancient group that originated from the Picosa tradition, and covered a territory that included present-day Apache, Flagstaff, the southern Deseret, and the Coloradan region. Other major ancient Indian civilization that rose to prominence were the Hohokam and Mogollon of present-day Cornerstone, Flagstaff, Maricopa, Sonora, and Pacífico Norte. These groups were noted for their extensive irrigation systems which sustained large agricultural projects, elaborate pottery, and distinct architecture. Such ancient civilizations disappeared within the past two millennia due to various, hypothesized factors including long-term droughts and famines.

With a number of exceptions, most Sierran natives generally lived as hunter-gatherers who resided across a variety of different environments, climates, and geography. Those further in the north along the coast and mountainous areas practiced forest gardening and even started controlled fires (using fire-stick farming methods) in the woodlands to sustain their agricultural habits. Some tribal groups such as the Chumash had larger, more sophisticated political organization including chiefdoms that encompassed large stretches of land. Trade, diplomacy, intermarriages, and military alliances were common forms of intertribal interactions. The indigenous peoples demonstrated a variety of skills and knowledge that made use of the resources of the land. The deliberate burning of the land prevented larger, catastrophic fires from occurring and revitalized plant growth that attracted consumable animals. Natives along the coast utilized boats for transport and had diets centered around fishing.

European exploration and settlement[]

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, the earliest known European to have explored Sierra

Francis Drake was the second known European to lead an expedition to Sierra

17th century engraving of Sebastian Vizcaíno, the first European to document Sierra's ecological features

European knowledge of Sierra prior to the region's exploration was heavily speculative, and interest was initially piqued by fantastical accounts depicted in the 16th-century Spanish romance novel Las Sergas de Esplandián (The Adventures of Esplandián) by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. The novel was a well-received commercial success in Spain and also achieved popularity throughout the rest of the Europe. The novel is set on the mythical island of California where black Amazon warriors led by Queen Califia and griffins inhabit the island. The Amazonians control a large cache of gold and pearls, and are heavily armed. Queen Califia fights alongside Muslims in the story and her name may have been chosen to sound like caliph, suggesting California may have been conceptualized as a caliphate. Various editions were produced, with the earliest known version published in 1510. Such content fueled European imaginations of the uncharted areas of the Americas including those in search of gold deposits and the fabled fountain of youth.

When the Spanish began exploring the Americas and reached the Baja California peninsula, which was rumored to be ruled by Amazonians, the Spanish named it California, erroneously believing the peninsula was an island, as the one described in Las Sergas de Esplandián. Although the exploration of the west coast of Mexico by Francisco de Ulloa that conclusively proved that Baja California was a peninsula, the belief that the peninsula was an island persisted in Europe, as evidenced through contemporaneous maps until the late 18th century. Mapmakers used the name "California" to refer to all the unexplored lands of the western North American coast during the 16th and 17th centuries.

In 1542, Spanish–Portuguese navigator Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (Portuguese: João Rodrigues Cabrilho) became the first European known to explore the Sierran mainland, reaching as far north as the mouth of the Russian River near Point Reyes on the coast of modern-day Central Valley. His expedition was commissioned and supported by New Spain's viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza. Cabrillo was unable to complete his trip and died at Santa Catalina Island of the Channels after developing gangrene from an injury wound on his shin. Cabrillo's successor, Bartolemé Ferrer, was able to continue the expedition and traveled as far north as Cape Orford in southern Astoria, becoming the first European to explore the southwestern coast of Astoria. In 1553, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés explored El Norte's Sonora and discovered the Baja California Peninsula during his final major expedition in the region. The Sea of Cortés was named in Cortés' honor by fellow Spaniard explorer Francisco de Ulloa. Cortés believed the peninsula was an island and named it "Santa Cruz Island".

In 1579, some 37 years after Cabrillo's expedition, English privateer Francis Drake traveled up the Sierran coast and claimed an indeterminate region there in the name of England and named the area "Nova Albion" (New England). The location Drake landed on was deliberately kept a secret by he and his men as Drake. He wanted to establish an English colony in the area and wanted to avoid detection by the Spanish. Drake was infamous amongst the Spanish and was known as El Draque by them due to his exploits and raids throughout New Spain. His claims went unrecognized as the British government neither formally recognized Drake's claims nor pursued any serious territorial control over Sierra.

In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno, under the commission of Viceroy Gaspar de Zúñiga, traveled along the coast of Sierra in search of pearls and mapped out the Sierran coastline. Between Drake's and Vizcaíno's expedition, there were numerous occasions where Spanish galleons traveling to or from Manila (Tondo) inadvertently landed on Sierran coastline for refuge and rest, beginning in 1565. According to Vizcaíno's accounts, he traveled as far north as Monterey Bay. During his expedition, he gave San Diego Bay, the King Louis Islands, Point Conception, the Santa Lucia Mountains, Point Lobos, Carmel River, and Monterey Bay their namesakes. Vizcaíno was also the first person known to document the ecological features of Sierra's coasts. Martín de Aguilar, a commander of one of Vizcaíno's ships, the Tres Reyes, got separated from the rest of the fleet and traveled further north, exploring the coastlines of Plumas and Shasta, and reaching as far north as southern Astoria (Oregon) by Coos Bay.

Hendrik Brouwer successfully founded a Dutch colony in Sierra

In 1644, Dutch explorer Hendrik Brouwer, on his way from Chile and towards Japan on a diplomatic mission, made an expedition to Sierra that was organized by the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) and Dutch West Indies Company. The Dutch desired a base along the North American Pacific Coast to trade gold and resupply ships returning from Asia, similar to the one attempted in Valdivia, Chile. Since the Dutch Republic and Spain were at war at the time, Brouwer wanted to establish a colony in the northern reaches of Alta California with the plan to eventually displace or disrupt Spanish presence there should conditions turned favorable on the side of the Dutch.

Evading detection by the Spanish, Brouwer established New Holland, a Dutch colony at the mouth of Noyo River (present-day Fort Brouwer, Plumas). Brouwer established friendly relations with the indigenous Yuki and Pomo, and left behind 20 men who founded the town of Brouwershaven in Brouwer's honor. The colony survived through intermarriages between the Dutchmen and indigenous women, and a crucial wave of emigrants expelled from the former Dutch Brazil in 1656. Although its existence was eventually discovered by the Spanish in 1769, New Holland remained under de facto Dutch control for nearly 140 years before the Netherlands capitulated to the Batavian Republic, and the French elected to formally cede New Holland to Spain through the Treaty of The Hague. The Spanish left the New Holland settlers alone despite the change, and the colony would not face interference until 1821 when the newly independent Mexican government asserted its authority over the region when it inherited New Spain's territory in Western North America.

Louise Antoine de Bougainville was responsible for leading a permanent French presence in Sierra

French admiral and explorer Louise Antoine de Bougainville toured the Spanish colonies of Alta California with his two ships (Boudeuse and Étoile) during a circumnavigational trip across the Pacific by commission of King Louis XV. Bougainville and his crew arrived from a trip to Tahiti and were warmly received by Spanish authorities at San Diego Bay. The admiral was impressed with the natural geography and landscape of Sierra and received permission by the local Spanish officials to allow 30 of his men to settle on Santa Catalina Island (Île Saint-Catherine) as a colony. With France and Spain on good terms, the French settlement on the Channels would become the French-Spanish Condominium, a joint colonial venture wherein the French were allowed to settle on Spanish territory.

In 1768, Jean-François de Galaup, a naval officer who was a part of Bougainville's expedition, returned to the Channel Islands with over a hundred French colonists including les filles du roi. Today, the majority of the Channeliers of French descent trace their heritage back to the people from the settlers who arrived from either Bougainville or Galaup's ships. The colony survived despite facing initial difficulties in portable water, resources, and a fire when the widely reported apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary occurred in the Santa Barbara Channel between the Channels and Grands Ballons in 1768. The event revitalized Spanish interest in developing Alta California and supporting the Frenchmen's endeavors in the Channels as the Spanish increased settlement, trade, and construction in the region soon thereafter.

Spanish period[]

Coat of arms granted to The Californias by New Spanish Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza

Following Vizcaíno's exploration and the establishment of the French-Spanish Condominium, Spanish activity and development in Alta California was stalled as Spain was preoccupied with European affairs. The Baja California Peninsula received significant attention however, as missions were established by Jesuit missionaries. The Jesuits received financial support from Viceroy Duque de Linares, who also successfully lobbied to the Spanish Crown of increased trade between Asia, Acapulco, and Lima. The peninsula became an important link in the transoceanic trade and was a region of prime interest for the Spanish Crown.

The report of the Virgin Mary in the form of Our Lady of Catalina in the Santa Barbara Channel rekindled Spanish interest in Alta California. The incident was widely reported among Spaniard soldiers, priests, and Channelier colonists, and accounts of the apparition captured the imagination and intrigue of Europeans and New World colonists alike. The end of the Seven Years' War allowed Spain to rededicate its attention towards its colonies in the Americas. In addition, the advances of the English and the Russians in the region prompted action from the Spanish. The failure of the Spanish to detect or realize the presence of the Dutch in the northernmost fringes of Alta California however, prevented a more urgent and stronger campaign to colonizing Sierra.

In 1767, following King Carlos III of Spain's decision to expel the Jesuits from the kingdom, New Spanish authorities were ordered to dispossess Jesuit power in the Californias. In 1769, newly appointed Governor of Alta California Gaspar de Portolá was sent to execute the order to remove the Jesuits and was tasked to explore Alta California. Portolà was accompanied by Franciscan monks Juan Crespí and Saint Junípero Serra y Ferrer, O.F.M., who were tasked with replacing the Jesuits and to extend the mission system that was successful in Baja California to Alta California.

Serra's first mission, Mission San Diego de Alcalá, was founded in 1769, was the first mission built in northern New Spain outside of New Mexico and Tejas (Brazoria). The first presidio in Alta California was also established in San Diego, and would serve as a military garrison for Spanish soldiers in the area. Serra, Portolà, and their men continued their exploration of Alta California northward, exploring the Porciúncula Basin and the Santa Barbara Mountains. The group received support from an envoy of Channeliers who happened to fish off the coast of modern day Grands Ballons. The Channeliers' claims of the Marian apparition years before persuaded Serra to found a mission in the region, Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. As they continued their travels northward, Serra founded another mission, Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, near Carmel-by-the-Sea, Kings. A total of 21 missions, including Serra's, would be established by the Franciscans between 1769 and 1833, which extended from San Diego to Sonoma. The El Camino Real (Spanish: The Royal Road) became an important route that connected all 21 missions together.

Las castas. Anonymous, 18th century, oil on canvas

The purpose of the missions was to Christianize and assimilate the indigenous people into European society. The missions were also constructed to affirm Spanish presence over its claims in California. The Spaniards were fearful of British intrusion in the region, and planned to gradually populate the area with Spaniards and mestizos who would keep Anglophones out of the area. Amerindians were forced to live near the mission in settlements known as reductions (reducciones). Over 140 Spanish Friars Minor were employed by the Spanish state to man the missions between 1769 and 1845. Amerindians were brought to the mission either by military force or economic incentive, as the missions were often the centers of trade, agriculture, and crafts. Baptized Amerindians were referred to as Template:Ds (new believers). Each settlement housed at least two friars together, and were allotted a corporal and his group of five or six soldiers who maintained order in the mission. Reinforcements and auxiliary support could be acquired from the several hundred soldiers distributed across Alta California's five presidios in San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, San Francisco City, and Sonoma. The Amerindians were subjugated under a racial-based hierarchy where they were exploited as uncompensated laborers, while mixed-race mestizos and European Whites had access to higher positions in the local society. There was also a small community of emigrants from North America, including Anglo-Saxon Americans and African Americans, the latter of whom became the progenitors of the modern-day Sierran French Creoles.

The Spanish colonial society operated under a racial hierarchy known as the casta system which was predicated on the concept of limpieza de sangre (cleanliness of blood). The system dictated the relationships and interactions between racial categories, as well as the rights and opportunities members from each group could expect. European-born Spaniards, known as peninsulares were at the top of the hierarchy, followed by full-blooded Spaniards born in the New World. Mixed-race mestizos, primarily those of mixed European and Amerindian heritage, constituted a growing majority of people living in Alta California, and served as a racial wedge between the white elites and the people of color below. At the bottom of the hierarchy were Amerindians and Africans. This race-based system remained a central component of the region's culture well after the end of Spanish administration, influencing racial relations in early Sierran history.

In 1809, France betrayed its alliance with Spain during the Peninsular War, which compromised Spanish dominance over its territories in the Americas, including Alta California. For nearly a decade and a half, Alta California and the Channel Islands operated under tenuous supervision of the local colonial government, and received financial support from Anglo-America and other parts of New Spain. In 1819, the Adam–Onís Treaty established the northern boundary of Spain's claims over Alta California at the 42nd parallel, establishing the present-day borders between Sierra and Astoria. The claim reaffirmed Spain's claim over the entirety of Sierra despite the continued presence of the Dutch in New Holland and its diminished power over the region. Spanish control and administrative power over Alta California had waned significantly by then however and by 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, thereby inheriting control over Alta California.

Mexican period[]

Vaqueros were herders who were prominent in Mexican Sierra's ranching-centric economy and way of life

Under Mexican control, Sierra's status remained as a geographically remote and minimally developed region. Californios and other inhabitants enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy due in part to the frequent government changes in Mexico. Alta California played a negligible role in the Mexican War of Independence and remained a territory as opposed to a state in the new regime. Initially, the Mexican government seldom intervened in local affairs although the authorities required that all citizens must be able to speak Spanish and practice the Catholic faith. Mexico did not effectively gain administrative control over Alta California until 1825, by which then, the region was affirmed as a territory under the 1824 Constitution. In order to solidify Alta California under Mexican law and order, the Mexican central government sent appointed governors to serve as the territorial executives. The first governor of Alta California was José Maria de Echeandía whose notable administrative actions included granting emancipation for the Amerindians living in mission lands and issuing land grants to private buyers.

In 1827, the Mexican passed the General Law of Expulsion which declared all persons born in Spain to be illegal immigrants and required them to leave Mexico, including Alta California. The law in Alta California specifically targeted the Franciscan monks assigned to the obsolete Spanish mission system, who were viewed with suspicion by the Mexican state as allies to Mexico's former colonizer Spain, as well as the Catholic Church. Many Spanish-born clergy complied with the orders, most of whom were of advanced age.

Signs of dissatisfaction by wealthy Californios with the Mexican government emerged during the governorship of Manuel Victoria. Opposition to the unpopular governor led to a brief rebellion which resulted in José Maria de Echeandía, the previous governor, to reassume governorship briefly again until 1833 when José Figueroa was appointed governor.

Political tensions persisted throughout the rest of the 1830s as the Mexican central government itself suffered the weight of sustained political instability and regime changes. Between 1833 and 1846, there was a total of 8 turnovers in Alta California's governorship, ending with Pío Pico. Most of the governorships were ended due to civil strife and armed rebellions by outraged citizens. The lack of serious military and logistical support from Mexico enabled the calamitous situation in Alta California to unfold unhindered.

During the 1840s, Alta California experienced an uptick in Anglo-American immigration and settlement. Enticed by the promise of good weather, cheap land, and adventure, tens of thousands of American pioneers and their families moved westward along a number of trails including the Old Spanish Trail in Southern Sierra and the Siskiyou Trail in Northern Sierra. In the decades prior, the majority of emigrants were American or British trappers from present-day Astoria and Canada who traversed into Mexican territory in search of beaver and other fur-bearing animals. In addition, significant numbers of people living in New Holland and the Channel Islands began emigrating to Alta California proper, with the primary factor being economic opportunism.

Mexican-American War[]

In 1846, hostilities between the Brazorian–American alliance and Mexico caused conflict to spillover into Alta California. The region was of significant interest for the American government, as well as the British and French governments, each of which had vested interest in acquiring control over the geographically expansive, resources-rich, and Pacific-bound territory. All three governments had offered previous proposals to buying Alta California partially or entirely from the the Mexican government. The Mexican government rejected all of the offers, despite suffering massive debt and insolvency.

Prior to the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, Alta California had a number of small-scale rebellions and revolts against the Mexican government. Californios were becoming increasingly concerned with what they saw an encroachment of their autonomy. The concurrent immigration of Anglo-American settlers in Alta California also further destabilized the political efficacy of the Mexican government over Alta California as the majority of English-speaking settlers lived outside of Mexican law. The Channel Islands and New Holland, both regions which enjoyed a significant degree of independence from Mexican interference, were also agitated with increased Mexican presence and efforts to rein in control over their livelihoods through taxation and other administrative actions.

The Treaty of Cahuenga was signed in modern-day Laurelwood, Gold Coast

On June 8, 1846, a group of Anglo-American settlers led by William B. Ide launched a rebellion and seized control over Mexican barracks in the city of Sonoma. The rebels carried banners which bore the image of a bear and a red star, known as the Bear Flag. The event, which came to be known as the Bear Flag Revolt, signified the beginning of California's armed and organized fight for independence. Soon afterwards, Sutter's Fort was seized by John C. Frémont. The Mexican government responded by sending troops to suppress the rebel forces in California. News of the rebellion and the war between the North American nations prompted many Anglo-American settlers in California to take up arms. Californios who were sympathetic to the Anglo-Americans' cause also rose up and joined forces. The self-declared California Republic and its army engaged in a series of conflicts throughout Alta California and extended their campaign southward towards the Baja California Peninsula and Sonora. On January 13, 1847, Californian forces and the Californios who supported the Mexican government signed an informal military agreement to end hostilities. The Treaty of Cahuenga ended the conflict in California itself as the Mexican forces gave up provided prisoners of war from both side were released by their captors. By the summer of 1847, the combined forces of the United States, Brazoria, and California overwhelmed Mexican forces and forced the Mexican government to surrender after Mexico City was captured. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally concluded the war and included Mexico's recognition of California's independence and sovereignty.

Post-independence[]

Early years[]

Although California gained independence as a sovereign state, the newly founded Californian government relied heavily on the military and economic support of the United States government. After the war, the Californian government incurred large sums of debt after it borrowed extensively from both the United States and Brazoria. In addition, it owed Mexico over $10 million in the form of a "grievance tribute" as stipulated by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. While Californian officials insisted that it remain independent, the United States government actively offered admission into the country as a U.S. state. The Californian government worried about the possibility of the American military taking over the newborn state by force if the Californian government defaulted on its debt. A number of Anglo-American citizens also conspired to declare allegiance to the United States. The Californian government lacked a standing army. Its only source of domestic defense were the militiamen who had assembled together loosely during the war. With the war over, most militias either disbanded or maintained their own quasi-legal existence. Lawlessness and corruption was rampant as lawmakers in Monterey (the first capital of California) struggled to draft a full-fledged constitution. These concerns were the central issue of the California Republic's brief, decade-long existence.

The young nation's independence continued to attract the attention and interest of immigrants due to its fertile land and economic opportunities. A diaspora of Scots and Irish émigrés arrived to California in search of resettlement. They were initially evicted from the United Kingdom due to the Highland Clearances and had settled along the Atlantic coast of the United States. A large number of these immigrants were supporters of Jacobitism and rallied around Charles Miller, a direct descendant of the deposed British Stuart king James II. Miller's family had amassed a fortune in the tanning and shipbuilding industry in the U.S. state of New Jersey and garnered novel attention by Jacobite supporters and third-party observers due to their familial and historical connections with the exiled British royal house. Miller embarked on a journey westward to California and hundreds of Jacobite families followed suit due to their loyalty and devotion to the Stuart bloodline.

Gold Rush of 1849[]

Prospectors searching for gold in 1850

On January 24, 1848, gold was discovered by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in present-day Coloma, Tahoe. News of the gold reached throughout California, Astoria (then known as Oregon Country), Mexico, Hawaii (then known as the Sandwich Islands), Peru, and Chile first. The California Gold Rush brought over 300,000 people to California from the rest of North America and beyond. The sudden influx of gold saved the Californian economy, allowing it to pay off its war debt, and provide much-needed funding for infrastructure, government services, and law enforcement. Over 300,000 people arrived within five years of the gold rush, overwhelming the country's limited resources and government. Lawlessness was rampant and prospectors or agronauts lacked protections from effectively non-existent property right laws. The majority of boomtowns and population growth occurred in Northern California, and San Francisco City became the most populous city in California.

The gold rush transformed California from a backwater country into a bustling nation. Over tens of billions of dollars worth of gold were recovered, although wealth was concentrated among a select few, most of whom would later become Sierra's first noble and aristocratic families. The majority of those who came in search of gold earned little if any increase in their fortunes.

Constitution of 1858[]

The population boom and unprecedented economic boom in California placed a significant strain on the government's resources, energy, and capabilities. The Californian government was unable to meet basic demands for law enforcement and funding public projects such as infrastructure. Elected officials at every level of government were accused of cronyism and corruption that were more invested in self-gain rather than public service. The Californian government had witnessed more than six presidencies over the course of ten years, with each president ending their terms out of resignation or electoral defeat. Among the international community, California was perceived as a lawless society which was unable to contain rampant vigilantism, corruption, and social unrest brought forth by the Gold Rush. Rumors that either the United States or Canada would invade California became a common topic of concern.

In 1852, amid race riots and labor shortages, a monarchist movement was organized in San Francisco City as Jacobites and sympathizers with anti-republican tendencies assembled to propose an alternative solution to California's "failed republican experiment". The Jacobites had recognized Charles Miller Stuart as their leader due to his royal blood and his open acquiescence to their fealty. Jacobite publications and newspapers began circulating the concept of a North American-based monarchy in California, which garnered support from Californians of various backgrounds including farmers, storeowners, factory workers, merchants, industrialists, and shipbuilders. The main arguments for monarchism promised stability and unity behind a monarchy which would moderate the populist demands of the public, preserve democracy under a manageable apparatus through a strong constitution, and control political opportunism by establishing a defined peerage system independent of the political system.

Early Kingdom years[]

A golden spike is driven down at the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad between the Royal Pacific and Central Pacific in 1869

The 1858 federal election was Sierra's first national election, held for nearly two weeks following the promulgation of the new constitution. Royalist party member Frederick Bachelor, Sr. became the first prime minister after his party secured 66% of the popular vote and 33 of the 50 seats in the House. Under Bachelor, Sr.'s first government, Sierra focused on expanding international trade and industrialism. The Sierran aristocratic class also developed as the monarchy rewarded titles to wealthy landowners, influential statesmen, entrepreneurs, and friends of the Crown. The Nobility Acts of 1859 formed the basis of Sierra's emergent peerage system, which was similar to the spoils system in other Anglo-American states at the time. The acts legitimized state recognition of lands awarded historically by the Spanish Crown and disproportionately favored Californios and their descendants, as well as Sierran citizens who had owned land under the California Republic or Alta California.

Although the Royalists maintained a comfortable numeric majority in Parliament and dominated San Francisco, Sierra's most populous province at the time, the Democratic-Republicans emerged as a capable, potent opposition party. Highly successful in the inland Styxie provinces, the Democratic-Republicans denounced Bachelor, Sr.'s ministry and expansion of the monarchy. While republicanism was one of the party's central issues, it also supported protectionism and the silver standard. During the 1863 elections, the Royalists maintained a majority in the House but lost four of its seats to the Democratic-Republicans, who achieved a modest seat gain in the House while the Whigs emerged as an early significant minor party with its first two seats.

As Sierra industrialized and the San Francisco Bay Area became more developed, tensions between the Royalist coast and the Democratic-Republican Styxie grew. Issues such as tariffs, immigration, the rise of the aristocratic class, and monarchism dominated the nation's partisan discourse. Under Bachelor, Sr., the Sierran government created numerous publicly owned corporations, including federally incorporated enterprises such as the Royal Postal Service and the Royal Pacific Railroad. A central bank, the Royal Monetary Authority of Sierra (ROMA) was also established in order to regulate Sierra's currency, public credit, and private banking institutions.

During Sierra's infancy, the country also experienced sporadic clashes with the local Amerindian tribes. The Sierran Genocide came to refer to all of the actions taken by the Spanish, Mexican, Californian, and then Sierran governments to decrease the population of the indigenous Amerindian peoples in Sierra. More than 10,000 Amerindians were believed to have been directly killed by Hispanic and Anglo-American settlers, and tens of thousands of more were killed indirectly from disease or poverty. The Sierran Indian Wars were a series of conflicts carried out by the Sierran federal government and provincial governments that occurred mostly in Northern Sierra between 1858 and 1880. The passage of the Compact Indian–Sierran Friendship Act represented the official end to this conflict and resulted in the creation of the modern Sierran Amerindian reservation system.

War of Contingency[]

Sierran soldiers massacring surrendered Union soldiers during the Battle of Litchfield

In 1861, the United States broke out into a civil war between the anti-slavery Union North and the pro-slavery Confederate South. Although Sierra remained officially neutral throughout the conflict, it continued trade with both the United States and the Confederate States. It did not formally recognize the Confederate States as a sovereign country, but maintained informal contacts with Confederate officials. By 1865, the war was over with a Union victory. Peace was short-lived as several months later, American President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, triggering a political crisis that derailed into a second Confederate Uprising. The uprising was successfully put down as the South was too weak to resist under the Reconstruction Union-controlled military governments, but other insurrections soon broke out across the rest of the country, leading to Grant's coup and Page's insurrection. These developments resulted in the secession of Northeastern states as the Northeast Union, Midwest states as Superior, and Tournesol. The United States government, on the brink of collapse, was reorganized under the Union of American States, which centralized power and sought to restore control over the newly seceded states, thus beginning the War of Contingency.

Sierra remained neutral on the onset of the conflict and signed the Grant-Trist Agreement with the Unionist government in order to declare nonaggression between the two states. Within a year, Sierran opinion of the war shifted due to concerns that the Unionist government was planning to conquer the entirety of the North American continent, including Sierra, and the presence of Unionist troops along the Brazorian–Sierran borders. Growing calls for interventionism and support for the seceding states were especially strong among Democratic-Republicans. Domestically, mounting unpopularity and resentment of pro-business and pro-industry policies resulted in the Democratic-Republicans under the leadership of Ulysses Perry gaining control over the House during the 1867 elections. Perry and his party's ascent to national leadership was met with fierce backlash by a Royalist-controlled Senate and House opposition, which forced three additional elections within the span of three years, two of which occurred in the same year in 1869 (one in February and the other in August). Parliament, under the premiership of Perry, declared war against the Union of American States, thus bringing Sierra directly into the conflict. This move was supported by populists but strongly opposed by industrialists and Royalists whose business interests were to maintain friendly relations and international commerce with the Union.

The main priorities of Sierra were to protect Sierran interests along its international borders, to maintain control over the Deseret, to prevent Unionist expansionism, and to assume political and military superiority in a post-United States North America. Sierran forces were quickly mobilized to transverse the Sierran East and through Brazoria to support the anti-Union forces. The Atlantic Squadron of the Sierran Royal Navy were also deployed to face off the Union Navy in the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic. Meanwhile, troops were sent north into the former Oregon Country where the Free State of Astoria was declared but was annexed by Canada. The resultant conflict, the Eugene War, was an early, but brief sub-conflict in the war which was a decisive victory for Sierra. Sierra signed a peace agreement with Canada in order to secure and guarantee independence for Astoria, and the assurance Canada would intervene in the War of Contingency on behalf of Sierra and the anti-Union states.

By mid-1868, Sierra and the anti-Union states had reversed much of the Union of American States' initial territorial gains and were making significant headway into Illinois, Kentucky, and Arkansas. Although the Second Confederate States surrendered to the Union, the entry of Canada all and Superior's capture of Michigan dampened the Union's prospects to retake these lands. Worn-out by years of intense warfare and mounting popular discontent, the Union of American States moved towards unconditional surrender. The Christmas Accords were signed on Christmas Day, 1868, which declared cessation of hostilities between the belligerent states, including Sierra. Months later, the war was officially concluded with the signage of the Treaty of Salinas. In the treaty, the Union promised to relinquish its claims over the breakaway states which now composed the Northeast Union, Superior, and Tournesol respectively, unless such states consented to reunification.

First Interwar period[]

The family of Henry D. Fitch were one of many aristocratic families which emerged in early Sierra and were targeted by Perry's reforms

With the war's end, Perry's popularity as the country's first wartime leader was major. National pride and morale ran high but Perry and his party continued to draw ire by the Royalist opposition. During and after the war as prime minister, Perry attempted to restrain the powers and influence of the monarchy, and to rollback aristocratic powers by implementing an estate tax, increasing property tax against property held by nobles and gentry, and banning the creation of new titles of nobility through the Pressings Act. He and his party referred to their reforms as the "Honest Deal" to voters. He helped pass the Royal Edict Limitation Acts, which restricted the use and effectiveness of the king's royal edicts to only enforcing existing statutory or constitutional law, rather than legislating new laws. Perry also transferred the King's power of the purse to the Privy Purse of Sierra, which would fall under the oversight of Parliament.

His attempts of government reform were strongly challenged by the Royalists. The Pressings Act was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the 1871 Wiesenfield v. Sierra case. He also sought to reduce the powers of the ROMA and lowered tariffs to provide injunctive relief for farmers. He made an unsuccessful bid to adopt the silver standard but unveiled a series of government subsidies and programs to support agricultural business.

Perry's commitment into the war in the East had also harmed business interests. While the war efforts incentivized industry to produce military armaments and supplies for short-term profit, few businesses were directly reached out by Perry's government and many saw the long-term consequences of a fractured, disunited East. There were fears that the war could damage the economy as labor would be drawn away to be conscripted as soldiers. Despite these fears failing to materialize and the success of the war, Sierra's involvement in the War was decried by critics as a "fool's brawl". Conservative resentment and opposition grew, and Perry's animosity towards the monarchy led to strained relations between the Crown and Parliament.

On February 14, 1874, Perry was assassinated by an unknown assailant and his body went missing. Federal investigators initially declared the cause of his death to be suicide, but conspiracy theories proliferated among Sierran republicans that Perry's death was the result of a politically-motivated murder by Royalist sympathizers. More radical republicans believed King Charles I himself ordered Perry's assassination, which sharply worsened the partisan climate of the country.

Sierran Civil War[]

Contemporary lithograph depicting the Capitulation of Isaiah Landon near Ridgecrest, Kings

The death of Ulysses Perry triggered great political and social unrest in the Styxie where the deceased prime minister was regarded as a martyr. Perry's deputy, Issac Johnson, became prime minister and tried to mediate peace between his party and the Royalist opposition. Calls for the abolition of the monarchy and the reinstatement of the Republic grew. The Democratic-Republican Party experienced factionalism between the Moderates who dominated the Senate and House Democratic-Republicans, and the Radicals who consisted of junior House members and populist local officials throughout the Styxie. Among the general populace, the Radicals quickly gained traction among disillusioned Democratic-Republicans in San Joaquin and Santa Clara, where republicanism were the strongest in. San Joaquin Senator Isaiah Landon rose as the most prominent advocate for radical republicanism. A personal friend and confidant of Ulysses Perry, Landon had gained notoriety for his writings on republicanism, as well as introducing Marxism to Anglo-American audiences. As the Johnson government continued to ignore the Radicals' demands for change, Landon led a rebellion in Bernheim, the capital of San Joaquin, thus starting the beginning of the Sierran Civil War.

Landon's insurrection resulted in the creation of the self-declared Second California Republic, with Reno, San Joaquin, Santa Clara, and Tahoe seceding from the Kingdom. The Republicans made swift gains on the rest of Northern Sierra, forcing the Sierran government to move its base of operations from San Francisco City to Porciúncula in the Southwest Corridor when San Francisco fell to the Republicans in December 1874. San Francisco, Plumas, Shasta, and parts of Central Valley came under Republican occupation by 1875, effectively dividing the country between the rebelling North and Kingdom South.

In 1875, Republican advances were eventually halted in Kings during the Folly at Tejon Pass, a battle which became the decisive turning point in the war. The Republican forces suffered major losses and pushback by the defending Monarchists. In the following months, the Monarchist forces recovered land lost in Central Sierra and began two campaigns to restore sovereign control over the rebelling Styxie. By 1877, Landon and the Republicans had resorted to scorched earth and other controversial tactics to hinder the Monarchists' attempts to regain control. Landon eventually surrendered and capitulated in mid-November of 1877. With the war effectively ended following Landon's surrender, Landon and other Republican leaders were arrested and tried for treason, sedition, and war crimes. Although Landon was initially sentenced to death by hanging, his sentence was commuted by King Charles I and was given a life sentence of house arrest instead. Major changes and reforms were implemented following the war, mainly to reintegrate the Styxie back into the Kingdom, and to control the influence of radical republicanism. The Democratic-Republican Party expelled officeholders who held radical republican tendencies and changed its platform from "hard republicanism" to "principled republicanism" that connoted cooperation and dialogue with the monarchy and its supporters.

Gilded Age and Sierran imperialism[]

An aerial view showing Porciúncula in 1887

HRMS Oakland and her crew played a critical role in Hawaii's annexation

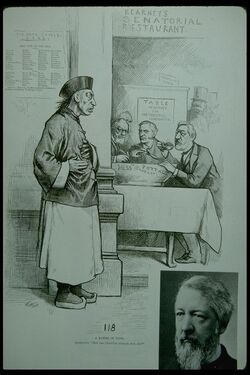

Political cartoon by the San Francisco Examiner depicting Collis P. Huntington as an octopus

Political cartoon satirizing the Nativists' attempts to exclude Chinese nationals from emigrating to Sierra

Following the war, Sierra experienced rapid economic recovery and revitalization in the Styxie. With the capital moved to Porciúncula, the city and the surrounding Southwest Corridor became the new political, economic, and social center. Various boomtowns and communities were developed as vast amounts of former rancho lands were resold back to the government or bought by private investors, developers, and companies. Improvements to transportation, manufacturing, and agriculture fueled the growth of industrializing cities.

By the 1890s, hundreds of miles of railroads were laid down to connect all of the major cities of Sierra with each other, as well as international destinations in Astoria, Brazoria, Superior, and elsewhere. The most significant lines were the Southern Pacific Railroad, Royal Pacific Railroad, Santa Fe Railroad, and Western Pacific Railroad. These lines carried both freight and passengers, which were vital to the country's economic growth and continued transcontinental migration. Electric railroads began to emerge during the last decade of the 19th century, with the largest system being developed and maintained by the Pacific Electric.

The discovery of oil across Sierra between the 1880s and the early 1900s further increased economic and commercial development. While agriculture remained the dominant industry in provinces such as Central Valley, the Inland Empire, and Orange, more and more farmland was converted into oil fields, factories, industrial depots, and housing to accommodate the nationwide explosive growth.

Coinciding with Sierra's industrial revolution was the enlargement of the Sierran military and the refinement of Sierra's foreign and military policies. The Sierran Royal Navy underwent a massive modernization plan which saw its fleet size grow more than quadruple its size during the Sierran Civil War. It experienced significant improvements to seafaring and naval warfare technology, as evidenced by its upgrade to steel-hull warships. Pre-dreadnought battleships were added to the navy's fleets by 1880s and reflected Sierra's Pacific-oriented foreign policy strategy of trade and regional dominance in the Pacific Ocean. During the mid-1880s, Sierra engaged in a series of military conquests and acquisitions of Pacific islands including the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, Rapa Nui, the Galápagos Islands. In 1893, Sierra annexed the Hawaiian Islands, which was the largest territorial gain by Sierra at the time since the country's inception. These acquisitions were emblematic of Sierra's goal to becoming an imperialist power, modeled after the imperial great powers of Europe such as Great Britain and France.

The period between the Sierran Civil War and the Sierran Cultural Revolution is commonly referred to as the Gilded Age by historians, so named due to rapid economic growth despite emergent social issues and economic inequality. Although real wages, wealth, and national GDP grew precipitously, political corruption, economic cronyism, and economic stratification plagued the country. "Robber barons" such as Collis P. Huntington and Leland Stanford were wealthy entrepreneurs who accumulated large amounts of wealth from their profitable enterprises and business ventures, often at the expense of Sierran workers. There were few worker's protection laws and labor unions lacked recognition by many provincial and local governments. Child labor was also widespread, especially within factories and mines. Although philanthropy and charitable giving was practiced by the wealthy and middle class to promote public works and social services, the overlooked issues among the working class remained largely neglected throughout this period by the federal government by the Royalists and Democratic-Republicans alike. Populist politicians and parties frequently contested in elections in order to capture the political dissatisfaction of the working class but only witnessed limited success in results. Immigration was another hot-button issue that persisted during the Gilded Age, as the citizenry were divided on immigration, particularly with immigrants from East Asian countries such as China and Japan, increasing the incidence of race-related conflict and growing antipathy among poor whites.

The worsening conditions were further complicated when Sierra had its first major banking panic in 1892 due to many financiers withdrawing their money from Sierran banks in response to the failing economies in Argentina and Brazil. Unemployment rates skyrocketed and prices were hiked, leading to social unrest and political mobilization among lower-class workers and farmers.

Nativist organizations were formed in response to Sierra's uncurbed immigration and financial woes, and were often linked with labor movements and syndicates. Supporters and pro-nativist lawmakers often pushed for anti-immigration laws, but did so to no avail. Prominent nativists, including Irish-Sierran Denis Kearney, threatened violence against business owners who hired Chinese. While anti-immigration measures failed due to resistance by the Royalists (who wanted cheap labor and strong relations with Asia), individual provinces such as those in the Styxie created discriminatory policies that restricted the civil rights of non-whites and passed literacy tests that made voting or even applying for a job much more difficult.

In 1893, King Charles I passed away following a year of severe health complications, making his eldest son, Crown Prince Lewis, the new king as Louis I. Similar to his father, he continued maintaining neutrality in domestic affairs while commanding a more active role in foreign policy. The new king rejected nativism but opted to reconcile with Democratic-Republican workers and cooperate with political reformists. Horrified by the social injustices and economic stagnancy that plagued the nation, he oversaw the introduction of the new labor policies such as the minimum wage and the eight-hour workday, regulated child labor under extreme standards, and the establishment of the imposing an income tax through the Royalist ministry of Prime Minister Joseph Sterling, a "progressive businessman" from Santa Clara. These reforms helped cultivate the rise of the Progressive Era as widespread social activism helped bring radical political reform to the country.

In 1898, Sierra along with several other Anglo-American states, mainly the Northeast Union, Union of American States and Brazoria, had participated in the Spanish–American War against Spain officially to oppose European imperialism in the Americas and to protect the sovereignty of states in the America, though the Sierran government used the war as a pretext to annex Spain's overseas territories and expand its empire even further. During the war, the Sierran Royal Navy made up a significant portion of the Combined American Fleet and fought in the Pacific Campaign where the Sierran Royal Marines and Army fought successfully against the Spanish and by the war's end had captured all of Spain's overseas colonies, including Tondo. During the war, Sierran forces were aided by Tondolese revolutionaries, but a renewed war between the former allies broke out in the form of the Han–Sierran War ending in 1901 with the establishment of the Sierran East Indies and a military occupation of the island to ensure Sierra's holdings in the region.

20th century[]

Progressive Era[]

Women's suffragists organizing a demonstration in San Francisco City

The excesses and social issues of the Gilded Age resulted in the emergence of Progressivism, a socio-political movement that was based on reform and change. Unrest and civil disobedience became a standard form of resistance and opposition to Gilded Age policies and society. Yellow journalism and the election of reform-minded, populist-oriented officials spurned interest in challenging the elitist culture which had developed in Porciúncula. The Progressive Era reflected a shift in Sierran society where there was an increasing sense of political efficacy that voting and active participation in government and politics could lead to practical, impactful change. Protests, organized strikes, marches, rallies, campaign drives, and petitions became more commonplace during this time. Continued advances in technology, medicine, science, engineering, agriculture, transportation, and electricity also hastened Sierra's trajectory towards a more modern, mobilized society.

In the 1901 federal election, the Democratic-Republicans under Robert Landon, the grandson of Isaiah Landon, became the governing party in the House. The party ran on a platform of Progressivism and civil rights, which included reversing economic inequality, protecting the working class, improving public health and sanitation, breaking up monopolies, extending full suffrage to women and people of color, introducing a federal initiative and referenda system, and regulating business more toughly. The party's policy changes reflected one that sought to bridge an alliance between the working class and the middle class. In 1903, it officially dropped political republicanism from its platform and supported the status quo of maintaining Sierra's constitutional monarchial system.

The Progressive movement also heavily influenced the Royalists as it attempted to moderate its own policies by supporting various reformatory policies which the Democratic-Republicans supported. The Progressive wing promoted a form of one-nation conservatism that believed the government could be used to improve the problems and issues of modern society. Unlike the Democratic-Republicans, the Royalists backed a platform which went further on racial equality and supported more socially conservative issues such as alcohol prohibitionism.

Sierran Cultural Revolution[]

Tondolese Catholics marching in 1924

The Sierran Cultural Revolution was a major period of social, cultural, and political upheaval which fundamentally altered and changed Sierran society. It originated out of the Progressive Era and coalesced into a wide-reaching, expansive movement that witnessed radically shifted views on race, culture, philosophy, politics, religion, and economics. The revolution began in 1901 initially as a grassroots-driven movement which consisted of a pan-racial coalition of mostly white European Sierrans, East Asian Sierrans, Hispanic and Latino Sierrans, black and Creole Sierrans, and mixed race Sierrans who promoted racial equality, civic nationalism, and multiculturalist harmony. The emergence of the Pacific School and its associated New Culture movement, best exemplified by Mark Culler's Comparison of Western and Oriental Thought, sparked a nationwide movement. The book pioneered modern Western methods of Chinese historiography and cultural studies. The book called for harmonization between Western European Protestant culture with East Asian Confucian culture, and spawned an entire intellectual trend of New Confucianists in Sierra. Rigorous and active campaigning for civil rights to Asians, Hispanics, and blacks led to increased social integration and coexistence. Growing acceptance and open adoption of new cultures between all ethnic groups evolved into a national, cohesive culture of similar customs and beliefs that consolidated elements from both Western and Eastern culture. The government, especially under the direction of King Louis I, began actively working and promoting the New Culture and engineered the Revolution to fit its aims and goals. The movement morphed into a top-down revolution that cracked down on Landonism, socialism, and other leftist ideologies in favor of a paternalistic, moralist democracy buttressed by capitalism and one-nation conservatism.

The Revolution was marked with widespread legal reforms, shift in attitudes and customs, increased immigration, and violent conflict with reactionaries. By its end, it saw the abolition of the Sierran casta system and radically altered the landscape of Sierran politics and social views. The Revolution also coincided with the rise of increased militarization, increased involvement of the monarchy, and authoritarianism due to widespread fear of Landonism, trade unionism, nativism, and anarchism. By the mid-1920s, during a time known as the Approbatio, the government resorted to military use and speech laws to control and suppress the activities of the opposition and dissidents. Contemporary historians have claimed that this later period in King Louis I's reign coincided with elements of derzhavism within the Sierran government. Although labor conditions worked, unions suffered greatly during the Revolution, and were subject to intense scrutiny. The change transformed Sierra into a cosmopolitan society and shaped the modern Sierran nation-state and democracy. The late Revolution coincided with unprecedented economic growth and militarization, propelling it towards the global power status it has reached in the present-day.

Although the Revolution was by no means uniform, and was not seen or referred to as a proper revolution until much later, it has been traditionally held that the Revolution began in the year 1901, from which its Sino-Sierran namesake owes its name to. Social change began in response to the effects of the Industrial Revolution and continued immigration of people from Asia and Latin America into Sierra, as well as Sierra's imperialist endeavors in the Pacific. Its colonization of Tondo was instrumental in bridging cultural exchange between the two powers and providing momentum for the Revolution. The rapid modernization and technological advancement of Sierra came at the cost of poor living conditions for the lower and middle classes and widespread corruption among Sierra's corporate elites. Immigration on the other hand, fueled racial tensions between the predominant Sierran whites and non-white immigrants who posed a threat to economic and labor interests. Miscegenation and the liberal exchange of different cultures had also produced a new class of multiracial Sierrans (such as the Sierran Creoles and the Hapas) and a more multiracial culture in the cities respectively. Social progressives and reformists sought to consolidate better conditions and rights to the disaffected commoners and to extend cordiality to new ethnic groups.

In 1909, King Louis I was crowned Emperor of Tondo, officially becoming a king-emperor. The phrase, "Kowtow to the King-Emperor" became a popular saying to refer to Louis I's full embracement as an emperor and an avid supporter of the Revolution. He positioned himself as a reform-minded monarch whose Orientalist sympathies made him a ready ally for prominent Revolution figures including Walter B. Feng and Richard Xiong. Although Louis I's traditional Jacobite supporters were mixed towards the King's acceptance of the New Culture, the Royalist Party sought to align its policies and agenda with the King. As a result, both the Democratic-Republican and Royalist parties officially supported the Revolution by 1911, and both attempted to court and curry favor from Sierra's rising Asian community.

Despite official backing from both major parties and the monarchy, there was widespread reactionary opposition to the changes ushered forth by the Revolution. The early opposition mainly consisted of traditionalists and nativists who sought to preserve ideals of white supremacy and rejected the New Culture's progressive thinking. Frequently, resistance turned violent, with numerous race-related riots, lynchings, pogroms in small communities, murders, and organized crime against minorities spearheaded by racist and nationalist organizations such as the Imperial Knights of Sierra (IKS) and the Workingmen's Party. The Reformed Republicans, an organized political party which upheld nativism, controlled the House of Commons briefly on two non-consecutive occasions during the 1920s, before being permanently displaced by the Democratic-Republican–Royalist system during the Approbatio period. Similarly, retaliation by pro-revolutionary forces also occurred, wreaking havoc to homes and businesses of counter-revolutionaries. These conflicts of resistance became known as the Little Civil War.

Approbatio[]

The Approbatio was a period of political turbulence and social unrest during the Revolution which was marked by numerous turnovers in the House and a progression towards increasingly authoritarian measures under the direction of King Louis I and his supporters. During the late 1910s, as the Revolution gained traction, opposition from both the left and right developed in reaction to it. The Democratic-Republicans were divided into three main camps: the Moderates, the Revolutionaries, and the Counter-Revolutionaries. While the former two supported the Revolution, the latter represented a coalition of mostly white working-class Styxers and political republicans who were alarmed at the rapid advances of the Revolution and believed that the Democratic-Republican Party had been subverted by Royalist infiltrators. Nativist and anti-Revolution leader Hiram Johnson became the leading figure of the Counter-Revolutionary Democratic-Republicans and vowed to restore the party to its pre-1903 platform.

Organized squadron of Purpleshirts paramilitary personnel in 1935

The resurgence of Landonism in the Styxie, as well as the outbreak of a Landonist revolution in the United Commonwealth was a significant security concern for Sierra. The First Crimson Scare referred to the widespread fear of far-left extremism in Sierra and increasing suspicion towards labor unions, trade unions, unionized workers, and leftist advocates. The workers' strikes in Bernheim in 1918 became cited as one of the key events which pushed the Revolution towards a reactionary turn. In addition, the emergence of Sierran-born Zhou Xinyue, who received training at The Presidio, The Military College of San Francisco, as a prominent military figure in the Continental Revolutionary War was seen as a national embarrassment and concern. Worried that the Styxie was a breeding ground for Landonists, calls were made to "pacify" the region. As progress was made underway towards racial equality and embracement for the New Culture, various Revolution supporters and leaders began to work alongside corporations, industrialists, and business-oriented voters who supported the pro-capitalist ideology of the New Culture. Socialism, particularly the variety that was most prominent with the Styxie, became identified as insurrectionist, anti-monarchist, and racist, as the Sierran left harbored a prominent underbelly of nativists and anti-Asian supporters.

The Revolution and the resultant culture wars produced a climate of division. Louis I, who feared about the possibility of another republican rebellion and civil war, turned towards the military for help. Edmond Xu, a Chinese Sierran Royal Army field marshal, was a strong proponent of the Preparedness Movement, which advocated the development of a strong military-industrial complex supported by big business and industry to defend the country from dissident leftism and foreign invasion. Xu's proposals were especially popular among the nation's bankers, industrialists, academics, lawyers, gentry, and other upper-class members, as well as Royalist politicians and a few Democratic-Republicans. They advocated strengthening Sierra's military capabilities, and emphasized the weak vulnerability of Sierran defense. In addition, supporters hoped the efforts towards increased militarization would quicken the process of racial integration between whites and Asians, as well as other races, and serve as the litmus test for a new form of civic nationalism. They wanted to assemble a well-trained, organized military that drew in recruits from all across the Kingdom's realms, including Tondo, regardless of class or race, which would bolster Sierra's image as a modern, multiethnic empire. Many proponents proposed a mandatory two-year service for all able-bodied male citizens between the ages of 17 and 45, a proposal which the King himself voiced support.

Sierran soldiers marching from New Mexico into Mexico

The movement was met with significant resistance from the Democratic-Republicans, as well as nativists, antimilitarists, pacifists, and some Royalists, who felt the proposals would bring Sierra into foreign entanglement. Some even expressed concern of the militarization as a gateway to authoritarianism, a fear that was already peddled by nativists who were critical of the Cultural Revolution policies. The Preparedness campaign elicited such a strong, polarizing response that it represented the first major controversial issue not tied to the race issue in the early 20th century. The Purpleshirts, originally known as the Order of the White Rose, originated during this time of militarization and emerged as a prominent, emblematic paramilitary force which exercised informal law enforcement authority. Under the leadership of the charismatic John Higashikata, the Purpleshirts' numbers quickly grew in the passing years, reaching 100,000 members by 1924. Its organization and acceptance by the government as a "cultural police" which inspected and punished individuals suspected of treason, sedition, or subversion was strongly criticized. Its legacy has been the subject of controversy as the Purpleshirts had an extensively documented record of extrajudicial killings and kidnappings of republicans, Landonists, and other Sierran citizens.

Clashes between the extremist, militant factions of the Revolution and the Counter-Revolutionaries were frequent in the Styxie and would come to be known as the Little Civil War, which became a low-intensity, decade-long conflict centered in the region. Security forces and secret police were deployed by the government to patrol and monitor the region which had been seen as the hotbed of resistance to the Revolution.

Lynch mob using a battering ram to breach a Bernheim-based business in 1933

During the Approbatio, Sierra moved away from its semi-isolationist foreign policy towards a more interventionist one. In Mexico, the escalation of the Mexican Revolution became an issue of prime interest for Sierra from both a geopolitical and domestic standpoint. Sierra feared that Mexico would fall under a Landonist regime supported by the United Commonwealth and wanted to protect its borders from possible infiltration or invasion. Sierra's navy also grew significantly as it strengthened its holdings in the Pacific and Tondo. While it had not fully become a great power, it became an important player in the international sphere, primarily through its power projection over the Pacific and in the Americas.

The electoral victory of the nativist-based Reformed Republicans under Hiram Johnson in 1919 reflected a divide between the Democratic-Republican establishment and its electorate. The offshoot party formed in reaction to the Democratic-Republicans' departure from political republicanism and Styxie-based values, and essentially split the vote. The Reformed Republicans entered into a coalition with the right-wing populist Know Nothings who championed nativism and anti-Catholicism, and were prevalent in Southern Sierra. The National Unionist was another party which had represented Royalist dissidents who had disagreed with the shift the Royalist Party underwent and joined the Reformed Republicans' coalition. Although the Reformed Republicans, Know Nothings, and National Unionist gained control over the House, their actual ability to legislate was hindered by the Royalists and Democratic-Republican opposition. The House members from both of the historic rivals entered an inter-party agreement, the Burbank Declaration, agreeing to resort to obstructionist tactics in order to thwart any meaningful legislation on the floor. The Reformed Republicans decried the declaration as anti-democratic and accused the King and the Senate for colluding with the House opposition. Two elections were held in 1920, one in March and one in September, each time held after Johnson sought to improve the number of seats in the House to overcome the opposition. While the Reformed Republicans were able to win in both elections, both yielded little net change to make an impact. Concerned with electoral fatigue and political maneuvering, King Louis I issued an edict to deny a third election which Johnson had planned in December. During the tumultuous electoral cycle, Sierra intervened in the United Commonwealth's Continental Revolutionary War alongside Brazoria and the Northeast Union. However, within three weeks, Sierra aborted its mission to support the Federalists and signed the Treaty of Bernheim, which ended Sierra's counterrevolutionary involvement and had Sierra formally recognize the Landonist regime as the successor state to the United Commonwealth.

In 1921, Democratic-Republican Phillip Judd led a coalition of both Democratic-Republicans and Royalists (retroactively referred to as the First National Government), to win a plurality over the Reformed Republicans and their coalition. Building upon the Burbank Declaration, the Democratic-Republicans and Royalists agreed to a temporary political alliance for the purpose of denying the Reformed Republicans the ability to continue "disrupting the Revolution". Setting aside economic differences and focusing on their mutual support for the cultural values and political gains of the Revolution, the First National Government sought to revise the House rules, notably by re-introducing the filibuster, which had been removed in 1902, and increasing the number of votes required to invoke cloture.

Conflict in the Styxie intensified as the National Government granted more authority to the Purpleshirts and introduced the controversial Sedition Act of 1922, a lèse-majesté law, which protected the King and members of the Royal Family from defamation, libel, and slander. The act criminalized any form of public criticism or insult against Louis I and his family. While the act was legally challenged and taken up to the Supreme Court, the Court ruled that speech or print critical against the King had "no constitutional value". The law was viewed as a direct threat to republicanism, as it made it a crime to criticize the King, although the law itself did not criminalize criticism against the institution of monarchy.

The Purpleshirts and local police cracked down on alleged seditious activity throughout the Styxie, especially in San Joaquin and Santa Clara. With habeas corpus effectively suspended in the region, accused and alleged "traitors" were often extrajudicially apprehended and prosecuted in provincial kangaroo courts. Hundreds of republican activists and other people deemed subversive to the state were killed by Purpleshirts agents or members of the public. The most infamous method of execution was lynching, although death by gun wound was just as prevalent. Numerous riots, civil disturbances, and racially-motivated pogroms also erupted during the 1920s and early 1930s.

Reformed Republican Hiram Johnson and Know Nothing Finn S. Pike successfully gained control over the House twice (1919 and 1923)

In 1923, the First National Government experienced a breakdown as Judd and other coalition leaders including Royalist Earle Coburn encountered disagreements and infighting over the progress of the Revolution. Judd and the Democratic-Republicans favored adopting economic measures which would strengthen workers' rights, believing it was crucial to the nation's economy and infrastructure while Coburn and the Royalists disagreed. Judd was himself accused by party members for compromising the party's economic values in favor of conciliatory relations with the rival Royalists. There was also disagreement over Sierra's involvement in Mexico and other Latin American countries. The Royalists were mostly composed of interventionists while non-interventionists and isolationists dominated the Democratic-Republicans. A group of 18 Democratic-Republicans, known as the Green Hounds, defected in February to the Reformed Republican coalition, and were able to pass a successful motion of no confidence. Hiram Johnson and the Reformed Republicans were able to regain control over the House, and vowed to overturn the Sedition Act, as well as rein in the powers of the Senate. It called for progressive economic policies, an isolationist foreign policy, and the abolition of birthright citizenship. More controversially, Johnson and the Reformed Republicans introduced eugenics into its party platform, calling for racial purity and the reintroduction of racial segregation and anti-miscegenation laws.

Johnson and the Reformed Republicans' grasp over the House lasted a little more than a year after months of legislative obstruction and official investigations into the activities of some Reformed Republican and Know Nothing politicians. In January 1924, the Royal Bureau of Investigation charged 11 members of Parliament and 3 senators including Reformed Republican Deputy Prime Minister John McNiall of corruption and conspiracy to commit treason. The Reformed Republican coalition itself faced internal disagreement and personality clashes between Hiram Johnson and Know Nothing leader Daniel J. O'Brien. Frustrated with legislative inaction, Johnson once again called for new elections but was defeated by the Royalists and Earle Coburn, who had been a major leader of the First National Government.

Coburn and the Royalists took advantage of the divide in the economic left to implement some welfare state policies. Hoping to draw and lure working class voters away from the Democratic-Republicans and Reformed Republicans, Coburn promised a national policy he called the Golden Ticket, which would introduce a national public pension fund, promise higher working wages, increase funding for public schools and universities, and bring economic relief for farmers and rural workers. He also adopted a friendlier approach towards labor unions, passing the National Labor Reform Act of 1925, which guaranteed workers the right to collective bargaining with any legally registered union. The shift in economic policy from laissez-faire economics to a more state-involved one among the Royalists reflected a larger nationwide trend towards a more "compassionate, softer" version of capitalism. As Landonism and other leftist ideologies persisted as popular alternatives throughout the Revolution, as exemplified by the economic success of the Landonist United Commonwealth, a labor-friendlier approach was perceived as the "antidote" by Coburn and other leaders to the "Green Menace".