| Imperial State of Iran کشور شاهنشاهی ایران Kešvar-e Šâhanšâhi-ye Irân |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: سرود شاهنشاهی ایران Sorude Šâhanšâhiye Irân ("Imperial Anthem of Iran") |

||||||

| Capital | Tehran | |||||

| Official languages | Persian | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | List of languages 53 percent Persian |

|||||

| Ethnic groups | List of ethnicities 61 percent Persian |

|||||

| Religion | 99.4 percent Shia Islam 0.6 percent Other |

|||||

| Demonym | Iranian Persian (historically) |

|||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | |||||

| • | Shah | Reza Pahlavi | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Maryam Rajavi (IP) | ||||

| Legislature | Deliberative Assembly | |||||

| • | Upper House | Senate | ||||

| • | Lower House | National Consultative Assembly | ||||

Establishment history | ||||||

| • | Median Empire | c. 678 BC | ||||

| • | Achaemenid Empire | 550 BC | ||||

| • | Parthian Empire | 247 BC | ||||

| • | Sasanian Empire | 224 AD | ||||

| • | Safavid dynasty | 1501 | ||||

| • | Afsharid dynasty | 1736 | ||||

| • | Zand dynasty | 1751 | ||||

| • | Qajar dynasty | 1796 | ||||

| • | Pahlavi dynasty | 15 December 1925 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 1,648,195 km2 (17th) 636,372 sq mi sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2019 estimate | 83,183,741 (17th) | ||||

| • | 2020 census | 86,813,413 | ||||

| • | Density | 48/km2 (162nd) 124.3/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | ▼ $1.471 trillion (18th) (18th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | ▼ $17,662 (66th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | ▲ $458.500 billion (25th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | ▲ $5,506 (95th) | ||||

| Currency | Rial (ریال) (IRR) |

|||||

| Time zone | IRST (UTC+3:30) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | IRDT (UTC+4:30) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ir ایران. |

|||||

| Calling code | +98 | |||||

The Imperial State of Iran (Persian: کشور شاهنشاهی ایران, romanized: Kešvar-e Šâhanšâhi-ye Irân), also known as the Imperial State of Persia from 1925 to 1935, is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia, to the north by the Soviet Union and the Caspian Sea, to the northeast by Turkmenistan, to the east by Afghanistan, to the southeast by Pakistan, to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, and to the west by Turkey and Iraq. Its central location in Eurasia and proximity to the Strait of Hormuz gives it significant geostrategic importance. Tehran is the capital and largest city, as well as the leading economic and cultural hub; it is also the most populous city in Western Asia, with more than 8.8 million residents, and up to 15 million including the metropolitan area. With 83 million inhabitants, Iran is the world's 17th most populous country. Spanning 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi), it is the second largest country in the Middle East and the 17th largest in the world.

History[]

- See also: History of Iran

Establishment and Reza Shah era (1925–1941)[]

- Further information: Reza Shah, 1921 Persian coup d'état

In 1925, after years of civil war, turmoil, and foreign intervention, Reza Khan, a former Brigadier-General of the Persian Cossack Brigade, deposed the Qajar dynasty and declared himself king (shah), adopting the dynastic name of Pahlavi, which recalls the Middle Persian language of the Sasanian Empire. Reza Shah established an authoritarian government that valued nationalism, militarism, secularism and anti-communism combined with strict censorship and state propaganda. He commenced an ambitious program of socio-economic, cultural, financial, administrative and military modernization. Iran, which had been a divided and isolated country under the rule of the previous Qajar dynasty, attempted industrialization.

Reza Shah's regime established schools, built infrastructure, modernized cities, and expanded transportation networks. To his supporters his reign brought law and order, discipline, central authority, and modern amenities such as trains, buses, radios, cinemas, and telephones. However, his attempts of modernisation was criticised for being "too fast" and "superficial", and his reign a time of oppression, corruption, taxation, lack of authenticity with "security typical of police states." Many of the new laws and regulations created resentment among devout Muslims and the clergy. For example, mosques were required to use chairs; most men were required to wear western clothing, including a hat with a brim; women were encouraged to discard the hijab; men and women were allowed to freely congregate, violating Islamic mixing of the sexes. By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's strong secular rule caused dissatisfaction among some groups, particularly the clergy, who opposed his reforms, but the middle and upper-middle class of Iran approved of his rule. Tensions boiled over in 1935, when bazaaris and villagers rose up in rebellion at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, chanting slogans such as 'The Shah is a new Yezid.' Dozens were killed and hundreds were injured when troops finally quelled the unrest. Also in 1935, Rezā Shāh issued a decree asking foreign delegates to use the term Iran in formal correspondence, in accordance with the fact that "Persia" was a term used by Western peoples for the country called "Iran" in Persian.

Reza Shah usually worked to keep a balanced foreign policy. Despite the treaties signed with the Soviets, Iran's relations remained cold due to Soviets' supporting the communist activities in Iran. In 1933, an important tension took place between Iran and the United Kingdom about the percentage that the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company would pay Iran. Getting closer to the Soviets again against Britain, the Shah managed to extend the duration of the nonaggression pact. The Saadabad Pact signed between Turkey, Iraq and Afghanistan in 1937 aimed at improving close friendship relationships with the neighbors and deactivating the potential interventions by the Britain and the USSR as well. Though many of his development projects required foreign technical expertise, he avoided awarding contracts to British and Soviet companies because of dissatisfaction during the Qajar Dynasty between Persia, the British, and the Soviets. Rezā Shāh preferred to obtain technical assistance from Germany, France, Italy and other European countries, and was pro-German and also felt close to the Italian fascism and the Japanese militarist system. Prior to World War II, he allowed a large number of German specialists and consultants to be in Iran. This created problems for Iran after 1938, when Germany and Britain became enemies in World War II.

World War II (1941–1945)[]

- Main article: Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran

Indian soldiers of the British Army guarding the Abadan Refinery in Iran, 4 September 1941.

On 3 October 1938 three days after the war broke out, Iran officially declared her neutrality. However, the British insisted that German engineers and technicians in Iran were spies with missions to sabotage British oil facilities in southwestern Iran. Britain demanded that Iran expel all German citizens, but Rezā Shāh refused, claiming this would adversely affect his development projects. In April 1941, the war reached Iran's borders when Rashid Ali, with assistance from Germany and Italy, launched the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, sparking the Anglo-Iraqi War of 1941. Germany and Italy quickly sent the pro-Axis forces in Iraq military aid from Syria but during the period from May to July the British and their allies defeated the pro-Axis forces in Iraq and later Syria and Lebanon.

With German armies highly successful against the Soviets during the summer of 1941, the Iranian government expected Germany to win the war and establish a powerful force on its borders. In July and August 1941 the British demanded that the Iranian government expel all Germans from Iran. Reza Shah refused to expel the Germans and on 25 August 1941, the British and Soviets launched a surprise invasion and overwhelmed the Imperial Iranian Army in Operation Countenance. The invasion's strategic purpose was to secure a supply line to the USSR (the Persian Corridor), secure the oil fields and Abadan Refinery (of the UK-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company), limit German influence in Iran, and preempt a possible Axis advance from Turkey through Iran toward the Baku oil fields or British India. Reza Shah's government quickly surrendered after less than a week of fighting. Following the invasion, on 16 September 1941 Reza Shah abdicated and was replaced by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, his 21-year-old son. Iran became the major conduit of Allied Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union, and an avenue through which over 50,000 Czechoslovak refugees and Armed Forces fled the Axis advance. Iran remained officially neutral.

However, at the end of the war, Soviet troops remained in Iran and established two puppet states in north-western Iran, namely the People's Government of Azerbaijan and the Republic of Mahabad. This led to the Iran crisis of 1946, one of the first confrontations of the Cold War, which ended after oil concessions were promised to the USSR and Soviet forces withdrew from Iran proper in May 1946. The Soviet republics in the north were soon overthrown and the oil concessions were revoked.

On 13 September 1943 the Allies reassured the Iranians that all foreign troops would leave by 2 March 1946, and at the Tehran Conference of 1943, the Allied "Big Three" — Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill — issued the Tehran Declaration to guarantee the post-war independence and boundaries of Iran. At the time, the Tudeh Party of Iran, a communist party that was already influential and had parliamentary representation, was becoming increasingly militant, especially in the North. This promoted actions from the side of the government, including attempts of the Iranian armed forces to restore order in the Northern provinces. While the Tudeh headquarters in Tehran were occupied and the Isfahan branch crushed, the Soviet troops present in the Northern parts of the country prevented the Iranian forces from entering. Thus, by November 1945 Soviet troops remained in Iran and established two puppet states in north-western Iran, namely the People's Government of Azerbaijan and the Republic of Mahabad. This led to the Iran crisis of 1946, one of the first confrontations of the Cold War, which ended after oil concessions were promised to the Soviet Union. Soviet forces withdrew from Iran proper in May 1946, and the two pro-Soviet puppet states fell by November 1946 and the oil concessions were later revoked, after support from the United States.

1946–1952: Post-war Iran[]

Discontent in Iran with British influence (1946–1951)[]

Following World War II, nationalistic sentiments were on the rise in the Middle East, the most notable example being Iranian nationalism. Nationalist leaders in Iran became influential by seeking a reduction in long-term foreign interventions in their country—especially the oil concession which was very profitable for the West and not very profitable for Iran. Iran's oil had been discovered and later controlled by the British-controlled Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), and Reza Shah was in 1933 forced to renegotiate the concession terms in favour of the British. Popular discontent with the AIOC began in the late 1940s, as a large segment of Iran's public and a number of politicians saw the company as exploitative and a central tool of continued British imperialism in Iran. The AIOC refused to allow its books to be audited to determine whether the Iranian government was being paid what had been promised.

Meanwhile, U.S. objectives in the Middle East remained the same between 1947 and 1952 but its strategy changed. Washington remained publicly in solidarity and privately at odds with its wartime ally. The British Empire was steadily weakening, and with an eye on international crises, the Truman Administration re-appraised its interests and the risks of being identified with British colonial interests.

Following World War II there were hopes that post-occupation Iran could become a constitutional monarchy. The new, young Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi initially took a very hands-off role in government, and allowed parliament to hold a lot of power. Some elections were held in the first shaky years, although they remained mired in corruption. Parliament became chronically unstable, and from the 1947 to 1951 period Iran saw the rise and fall of six different prime ministers. At least two unsuccessful assassination attempts were made against the young Shah. On 4 February 1949, he attended an annual ceremony to commemorate the founding of Tehran University. At the ceremony, Fakhr-Arai fired five shots at him at a range of c. three metres. Only one of the shots hit the king, grazing his cheek. Fakhr-Arai was instantly shot by nearby officers. After an investigation, it was thought that Fakhr-Arai was a member of the Tudeh Party, which was subsequently banned.

Shocked by the experience and emboldened by public sympathy for his injury, the Shah began to take an increasingly active role in politics. He quickly organized the Iran Constituent Assembly to amend the constitution to increase his powers. He established the Senate of Iran which had been a part of the Constitution of 1906 but had never been convened. The Shah had the right to appoint one-half of the senators and he chose men sympathetic to his aims. Mohammad Mosaddegh thought this increase in the Shah's political power was not democratic; he believed that the Shah should "reign, but not rule" in a manner similar to Europe's constitutional monarchies.

Under the leadership of Sir William Fraser, a famously obstinate Scotsman who hated the idea of compromise, the AIOC rejected every appeal to reform. Three months after the assassination attempt on the Shah, Fraser proposed a contract known as the Supplemental Agreement, intended to supplement the one Reza Shah signed in 1933. It offered Iran several improvements: a guarantee that Anglo-Iranian’s annual royalty payments would not drop below £4 million, a reduction of the area in which it would be allowed to drill, and a promise that more Iranians would be trained for administrative positions. It did not, however, offer Iranians any greater voice in the company’s management or give them the right to audit the company’s books. Prime Minister Mohammad Sa'ed took this proposal as a basis for discussion and invited Fraser to negotiate their differences, but Fraser dismissed him and declared that his offer was final. The Shah, who knew he must do what the British wanted, ordered the cabinet to accept the Supplemental Agreement, which it did on 17 July 1949.

The agreement had to be approved by the Majlis, and many members of the Majlis publicly denounced the Supplemental Agreement even before the cabinet accepted it. One outraged deputy, Abbas Iskandari, gave an impassioned speech denouncing the agreement that finished with a warning so far-reaching that even he may not have grasped its implications. One of the MPs, Iskandari, demanded that AIOC begin splitting its profits with Iran on a fifty-fifty basis, as American oil companies were doing in several countries. If it refused, Iran would nationalize the oil industry. The approval of the Agreement were left for the next Majlis.

On 28 July 1949, the term of the 15th Majlis came to its natural end, and preparations to hold elections for the 16th Majlis, including Iran's first Senate, were initiated. The Shah began selecting the 30 senators that were his to choose. In the Majlis, the Shah resolved to do whatever necessary to assure that the next Majlis would heed him. Using a variety of techniques ranging from the recruitment of royalist candidates to bribery and blatant electoral fraud, he managed to secure the election of many pliable deputies. The election was held, and it became clear that rural Iran was voting in favor of royalist supporters of the Shah. Several cities exploded in protest, and Mosaddegh reacted to what they saw as rigged results in rural elections by organizing a protest on 13 October 1949. Thousands of workers, students and middle-class people gathered at his Mosaddegh's estate and marched on the roal palace. In a meeting with Interior Minister Abdolhossein Hazhir, 20 opposition and radical politicians led by Mosaddegh demanded a halt to the Shah's hindrance of free elections. After three days of sit-in protest they extracted a promise from Hazhir that he would conduct elections fairly. Directly afterward, the committee of 20 formed the National Front coalition. In the following weeks, the investigation of the elections commenced, as many Iranians thought there would be some sort of smooth coverup of royal wrongdoing. However, on 4 November 1949, Hazhir was assassinated. The Shah thus realized the depth of popular feeling formed against his electoral machinations, he declared the voting results invalid on 11 November. New elections were to be held in February 1950.

In February 1950 at the conclusion of elections for the 16th Majlis, the National Front took eight seats in the Majlis — Kashani and Mosaddegh both won seats — and from that platform for the next few years continued to call for reductions in the power of the monarchy; a return to the Constitution of 1906. With the backing of the extremist Fada'iyan, the regular clergy, and the middle-class people, despite its minority toehold in parliament, the National Front became the main opposition movement of Iran.

On 20 June the Majlis voted to create an eighteen-member committee to study the Supplemental Agreement. The British took this as an act of defiance and advised the Shah that he must respond by sacking Prime Minister Ali Mansur and naming General Ali Razmara to succeed him. Razmara replaced Mansur as Prime Minister on 26 June 1950. By this time the Majlis had named the members of its oil committee, including Mosaddegh, with many of its members being no more interested in finding a compromise than AIOC was. On 25 November 1950 Mossadegh brought the Supplemental Agreement to a vote in his parliamentary committee. Mossadegh and the four other committee members who belonged to the National Front proposed the radical option of nationalizing AIOC, but the rest of the committee was not ready to go that far. On the question at hand, though, there was no dissent. The committee voted unanimously to recommend rejection of the Agreement.

Events now began to take on a momentum of their own. Iranian politics was moving into uncharted territory, and there was no steady hand at the tiller of state. Every day positions grew more polarized. No faction believed in the goodwill of any other. Discourse was conducted by insult and tirade. At the end of December, news reached Tehran that the Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO), had reached a new deal with Saudi Arabia under which it would share its profits with the Saudis on a fifty-fifty basis. Ambassador Sir Francis Shepherd immediately dispatched a cable to London urging that the AIOC make a similar offer to Iran. Both the British Foreign Office and the oil company rejected the idea.

Confrontation now seemed inevitable. In January 1951 Iranian nationalists called a rally to launch a mass-based campaign aimed at forcing the nationalization of AIOC. A huge crowd turned out. Prime Minister Razmara was now in an impossible position. The masses had long since decided that he was at best a pawn of the British and at worst a traitor. He replied by insisting time and again that protesters, both inside the Majlis and outside, were pursuing a mad dream, and that the country’s interest required it to make a deal with the British. But although he worked feverishly to salvage the British position, neither AIOC nor the Foreign Office gave him a shred of support. On 3 March he appeared before Mossadegh’s oil committee and once again explained his opposition to the idea of nationalization. He said it would be illegal, would drive the British to unpredictable retaliation, and would devastate Iran's economy. Iranians suspected that the British had dictated Razmara's speech and reacted with another outburst of protests on 7 March. Razmara was out of time, and the Shah had quietly begun asking politicians of various stripes whom they would suggest as a new prime minister. Each gave the same answer: Mossadegh. That same day, Razmara was assassinated by the hardline Fadaiyan e-Islam (whose spiritual leader the Ayatollah Abol-Qassem Kashani, who had been appointed Speaker of the Parliament by the National Front). After a vote of confidence from the National Front dominated Parliament, Mosaddegh was appointed Prime Minister by the Shah on 28 April 1951.

Nationalisation of the oil industry and Abadan Crisis (1951–1952)[]

The British ambassador Shepherd met with Prime Minister Ala and suggested for the first time that AIOC were ready to consider the idea of a fifty-fifty profit split, which was refused by Ala. On 15 March 1951 the Majlis met to cast its vote on the oil nationalization agreement, with all votes in favour. Five days later the Senate also voted its unanimous approval. On 1 May 1951, Mohammad Reza Shah signed the law revoking AIOC's concession and establishing the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) to take its place. The next day Britain demanded that the law be suspended. On 6 May Mosaddegh submitted his cabinet to the Majlis. It was immediately approved, and on that same day Mosaddegh took office as prime minister.

The bill was widely popular among most Iranians, and generated a huge wave of nationalism, while Mosaddegh was now a hero of epic proportions, unable even to step onto the streets without being mobbed by admirers. Tribal leaders in the hinterlands celebrated his triumph, Ayatollah Kashani lionized him as a liberator on the scale of Cyrus and Darius, and even the communists of Tudeh Party embraced him. Over the next few weeks the Majlis voted overwhelmingly for every bill he presented. Many Iranians felt that for the first time in centuries, they were taking control of the affairs of their country. Many also expected that nationalization would result in a massive increase of wealth for Iranians.

Britain now faced the newly elected nationalist government in Iran where Mosaddegh, with strong backing of the Iranian parliament and people, demanded more favorable concessionary arrangements, which the British vigorously opposed. The British and their American ally disagreed strongly over how to deal with Mosaddegh. On 18 May the U.S. State Department issued a public statement declaring that Americans "fully recognize the sovereign rights of Iran and sympathize with Iran’s desire that increased benefits accrue to that country from the development of its petroleum." U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson and others in the Truman administration never stopped urging their British counterparts to turn away from their policy of confrontation and to offer Iran a legitimate compromise. Prime Minister Attlee seemed disposed to compromise. Attlee was a socialist who had helped draft the plans under which Britain had nationalized some of its own basic industries, and at one cabinet meeting he suggested that Britain might make a public statement accepting nationalization of AIOC and then arrange some sort of complicated deal under which the company would retain most of its privileges. Foreign Secretary Herbert Morrison vigorously objected, warning that any concessions to Iran would set an intolerable precedent and encourage nationalists everywhere. Despite Morrison's protests, Attlee agreed to send a delegation led by AIOC's deputy chairman Basil Jackson, to negotiate with the Iranians. Morrison resigned subsequently as Foreign Secretary and was replaced by Kenneth Younger. However, Mosaddegh welcomed them by arranging for Iranian gendarmes to take over the Anglo-Iranian office at the western town of Kermanshah on the day they arrived.

Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh rides on the shoulders of cheering crowds in Tehran's Majlis Square, outside the parliament building, after presenting the 50-50 Consortium Agreement to his supporters on 13 September 1951.

The Iranians negotiators stated they were willing to talk, but only after the British accepted nationalization as a fait accompli. The British counter offered that AIOC paid Iran £10 million and another £3 million monthly while negotiations proceeded; as well that AOIC transferred its assets to the newly created National Iranian Oil Company under the condition that they could establish a new company that would have "exclusive use of those assets." Iranian negotiators rejected the offer. On 20 June, Mosaddegh named a French-educated engineer, Mehdi Bazargan, as the managing director of the National Iranian Oil Company, who flew to Abadan and declared himself.

With the negotiations stalled, U.S: President Truman, still hoping to find a solution to the crisis, convinced the British to let a delegation led by W. Averell Harriman to mediate. After instructions from the U.S. State Department, the U.S. Ambassador in Tehran, Henry F. Grady, urged Czechoslovakia through ambassador Miroslav Kundrát to convince Mosaddegh to adopt a conciliatory attitude. As one of Iran's largest European trade partners and position as a neutral, medium-sized state with no political interests in the country as a superpower, the State Department hoped that the Czechs could sway the Iranians toward a compromise. After meetings with Ambassadors Grady and Kundrát and the Czechoslovak Foreign Minister, Štefan Osuský, Mosaddegh agreed to receive the delegation.

On 6 July 1951, the delegation led by W. Averell Harriman, and also comprising U.S. Assistant Secretary of State George McPhee, arrived in Tehran. Mosaddegh's plan, based on the 1948 compromise between the Venezuelan Government of Romulo Gallegos and Creole Petroleum, would divide the profits from oil 50/50 between Iran and Britain. After weeks of fierce negotiations, Iran and Britain signed the Consortium Agreeement on 12 September 1951 based on the 50-50 principle. An international consortium was organized, where the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) held 50 percent of the shares, AIOC (renamed into British Petroleum in 1952) held 26 percent, the French Compagnie Française des Pétroles (later Total S.A.) held 4 percent, while the four ARAMCO partners — Standard Oil of California (SoCal, later Chevron), Standard Oil of New Jersey (later Exxon), Standard Oil Co. of New York (later Mobil, then ExxonMobil), and Texaco — each held a five percent stake. The non-British companies paid AICO $2 billion for their 74 percent. It agreed to share its profits with Iran on a 50-50 basis and to open its books to Iranian auditors or to allow Iranians onto its board of directors.

1952–1969: First democratic era[]

1952–1961: Reign of Mosaddegh and transition to multi-party democracy[]

Prime Minister Mossadegh at a National Front rally during the election campaign of 1953.

While the Communists in the Tudeh Party and some Islamist conservatives were disappointed with Mosaddegh for compromising instead of opting for full nationalization, the agreement triggered an explosion of celebrations. Crowds poured onto the streets of Tehran and other cities, celebrating Mossadegh for having defeated Attlee and the British into giving the Iranians concessions. Mossadegh's support was now broad and fervent that he called upon the Shah to call for elections for an Iranian Constitutional Assembly to be held in 1952.

Elections for the Iranian Constitutional Assembly were held on 5—6 February 1952, and were the first free multi-party elections in Iran's history. The National Front — which included the nationalist and social democratic Iranian Party, the socialist Toilers Party of the Iranian Nation, the liberalist People's Party and the Islamist Society of Muslim Mojaheds — won a majority, while the conservative and monarchist National Union Party and the Communist Tudeh Party also entered parliament. Fearful of the influence of the leftists, the Shah asked if Mossadegh still wished to maintain the monarchy. Mossadegh assured him that he did, presuming of course that kings would accept the supremacy of elected leaders: "You could go down in history as an immensely popular monarch if you cooperated with democratic and nationalist forces." The Shah urged his conservative supporters to have a conciliatory attitude and participate in the democratic process. On 28 August 1952 the assembly approved the draft constitution proposed by the National Front, and in a referendum on 13 October 1952, 93.6% percent of the Iranians participating in it approved the constitution.

In the legislative election of 23—24 February 1953 the National Front strengthened their majority. The Mosaddegh's administration introduced a wide range of social reforms: unemployment compensation was introduced, factory owners were ordered to pay benefits to sick and injured workers, and peasants were freed from forced labor in their landlords' estates. In 1953, Mossadegh passed the Land Reform Act which forced landlords to turn over 20 percent of their revenues to their tenants. These revenues could be placed in a fund to pay for development projects such as public baths, rural housing, and pest control. Mosaddegh supported women’s rights, defended religious freedom, and allowed courts and universities to function freely. Above all, he was known even by his enemies as scrupulously honest and impervious to the corruption that pervaded Iranian politics.

National Front demonstration in support of Mossadegh's reforms, February 1954.

Mossadegh introduced various economic and social reforms, with the ultimate long-term aim of transforming Iran into a global economic and industrial power. Modernization and economic growth proceeded at an unprecedented rate, fueled by Iran's vast petroleum reserves. Inspired by the Five-Year Plans of Soviet Union, the First Iranian Five-Year Economic Development Plan was proposed by Finance Minister Bagher Kazemi and approved by Prime Minister Mosaddegh and the Shah in 1954 for period 1954–1959; it gave highest priority to heavy industrial development, expansion of banking and financial services, an advancement in education, and nationalization. Forests and pasturelands were nationalized to prevent their destruction and further develop and cultivate them. More than 9 million trees were planted in 26 regions, creating 70,000 acres (280 km²) of green belts around cities and on the borders of the major highways. All water resources were nationalized and projects and policies were introduced in order to conserve and benefit Iran's limited water resources. Many dams and hydroelectric facilities were constructed. It was as a result of these measures that the area of land under irrigation increased from 2 million acres (8,000 km²), in 1955, to 5.6 million in 1964.

On 4 September 1954 the Majlis passed the Health Corps Law (Sepah-e Behdascht), which extended public health care throughout the villages and rural regions of Iran. Conscripted doctors, dentists, veterinarians and those trained in health care could serve in the Health Corps instead of their mandatory military service. In 3 years, almost 4,500 medical groups were trained; nearly 10 million cases were treated by the Corps. The Comprehensive Education Law of 13 July 1956 established the Ministry of Education and the Literacy Corps (Sepah-e Danesch), which was tasked with fighting illiteracy in the villages. The rate of illiteracy for adults in the villages was 95% at the beginning of the program, as many who could read and write failed to show a regular certificate from school. With the Literacy corps, those who had a high school diploma and were required to serve their mandatory military service could do so by fighting illiteracy. From 1956 to 1969, more than 2.2 million children and more than 1 million adults were taught by nearly 200,000 young men and women. Ten years after the program started, the number of illiterates in the villages as below 80%. Only those who could prove their education and qualifications were registered as able to read and write. In 1962, 293,000 village students were taught in 74,141 schools recently built as part of the literacy program; In 1969, there were already 656,000 students in 14,732 new schools. In 1961, 493,247 students were taught by the program, in 1962 the numbers reached 861,657 students.

Profit sharing for industrial workers in private sector enterprises was introduced in 1957, giving the factory workers and employees 20% share of the net profits of the places where they worked and securing bonuses based on higher productivity or reductions in costs. With the 1956 Land Reform, large landowners were only allowed to own one village and had to sell the rest of their land to the state which in turn was to sell it to the landless farmers at a significantly lower price. The state also granted farmers cheap loans when they formed agricultural cooperatives. At the 1957 elections the National Front saw their majority in the Majlis but with Mossadegh continuing as Prime Minister, and he could continue his reform program with the endorsement of the Shah. The formation of the Reconstruction and Development Corps in 1958 was intended to teach the villagers the modern methods and techniques of farming and keeping livestock. Agricultural production between 1959 and 1965 increased by 80% in tonnage and 67% in value.

The second five-year plan introduced in 1959 gave highest priority to heavy industrial development, a comprehensive land reform, and an expansion of the social security system. Further improvements were made in railways, communications, and transportation. More attention was given to private sector industrial development and agricultural industries. Most important was the Land Reform of 1960. Mosaddegh had spoken of the need for land reform for many years but the clergy resistance had repeatedly led him to postpone the reform. With the endorsment of the Shah, the government could now buy the land the feudal landlords at what was considered to be a fair price and sell it to the peasants at 30% below the market value, with the loan being payable over 25 years at very low interest rates. This made it possible for 1.5 million peasant families, who had once been little more than slaves, to own the lands that they had been cultivating all their lives. The land reforms program brought freedom to approximately 9 million people, or 40% of Iran's population.

While Mosaddegh remained popular throughout his tenure as Prime Minister by a large part of the population, his reforms met criticism from the the Shīah clergy and the landlords. The landlords were angry that the land reforms allegedly violated the constitution and the country's existing laws, that the land was bought by the government and then sold at a lower price, as well that the government undercut their authority when it came to dealing with peasants or land laborers. The clergy accused the land reform to violate the laws of Islam. It became clear that the land reform against the resistance of the large landowners and the clergy could only be implemented if it were supported by the vast majority of the Iranian population. For this reason the Mosaddegh government planned a referendum in which Iranian citizens should vote on whether they would approve or reject the reform plans. The referendum passed with 73.91% of voters voting for the reforms. Following the referendum, Prime Minister Mosaddegh, now years 79 old, announced his resignation and calling for elections.

By the end of Mossadegh's reign, the country's gross national product had grown by 10.6% annually, and the oil, gas and construction industries grew by almost 300% from 1951 to 1961. With the Concession agreement, oil revenues increased from $34 million in 1953–1954 to $358 million in 1960–1961.

Foreign policy (1952–1969)[]

Following the conclusion of the Abadan Crisis, relationship United Kingdom remained strained, while Iran's foreign policy made an effort to adhere to non-alignment and to balance relations with both the United States and the Soviet Union. Iran's foreign policy was to a large degree formed by Hossein Fatemi, who served as Foreign Minister from 1952 to 1965. Drawing on the principles agreed at the Bandung Conference in 1955, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was established in 1961 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia through an initiative of Mosaddegh, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, Indonesian President Sukarno, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito. On 14 September 1960, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela establish the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to rival the mostly Western companies dominating global oil supplies and to reestablish control over their domestic oil reserves.

In 1955, Mossadegh condemned the signing of the Baghdad Pact between Great Britain, Turkey, Iraq and Pakistan, and the following year he supported Egypt during the Suez Crisis and the Anglo-French-Israeli military intervention. intervention. In 1957, the Mosaddegh government demanded that the island of Bahrain (which Britain had controlled since the 19th century, but which Iran claimed as its own territory) be transferred to Iran.

During this period, Iran maintained cordial relations with the Persian Gulf states and established close diplomatic ties with Saudi Arabia. The Mosaddegh government saw Iran as the natural dominant power in the Persian Gulf region. Iran's relations with Iraq, however, were often difficult due to political instability in the latter country. While Mosaddegh was more positively inclined, the Shah was distrustful of both the Socialist government of Abd al-Karim Qasim and the Arab nationalist Baath party. He resented the internationally recognised Iran-Iraq border on the Shatt al-Arab river, which a 1937 treaty fixed on the low watermark on the Iranian side, giving Iraq control of most of the Shatt al-Arab. On 19 April 1969, the Shah abrogated the treaty, and as a result Iran ceased paying tolls to Iraq when its ships used the Shatt al-Arab, ending Iraq's lucrative source of income. He justified his move by arguing that almost all river borders all over the world ran along the thalweg (deep channel mark), and by claiming that because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian, the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran. Iraq threatened war over the Iranian move, but when on 24 April 1969 an Iranian tanker escorted by Iranian warships sailed down the Shatt al-Arab without paying tolls, Iraq, being the militarily weaker state, did nothing. The Iranian abrogation of the 1937 treaty marked the beginning of a period of acute Iraqi-Iranian tension that was to last until the Algiers Accords of 1975.

Despite Mosaddegh's open disgust with communism, he and the National Front had formed an unofficial alliance during the nationalization crisis, and the Tudeh Party had endorsed some of the reforms. Military studies had indicated that Iran could only hold out for a few days in the event of a Soviet invasion. That, along with his fear of the Tudeh Party's motives and a possible Communist takeover, Mosaddegh saw improving relations with the Soviet Union as a means of checking the power of the Tudeh Party. On 17 April 1957 the Soviet-Iranian Non-Aggression Pact was signed, in which the parties solemnly promised not to use military force against each other, as well as renounced any mutual territorial and other claims. In 1959, a major agreement on economic and technical cooperation was signed in Tehran. It envisaged cooperation in the construction of the sites which were important for the development of economies of both countries, such as hydro-technical facilities on the frontier river Aras (a dam, a water reservoir and two electric power stations), sturgeon-breeding plant, grain elevator, melioration works in the region of the Bay of Mordāb on the Caspian, and others. Financing of the works was arranged on an equal footing. For the purpose of paying for the supply of equipment and technical services from the USSR, Iran was given a twelve-year credit to the amount of 35 million rubles with annual interest rate of 3.6 per cent. It was envisaged that the loan could be repaid through the export of Iranian goods to the USSR. Following a visit to the Soviet unionn in June 1962, the Iranians signed an arms-deal where the Soviets agreed to sell some $110 million worth of weaponry.

Relations with the United States were initially tense, due to scepticisms that the U.S. were supporting the British against the Iranians. While several leading members of the Eisenhower Administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles, feared Mosaddegh's dependence on the Tudeh Party would destabilize Iran and possibly lead to Mossadegh's overthrow and replacement by a Tudeh government controlled from Moscow. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who considered Mosaddegh "the only hope for the West in Iran," committed the administration to conciliatory policy towards Mosaddegh. From 1954 to 1960, the United States gave Iran $1.2 billion in aid and sold $583 million worth of weaponry. On 5 March 1957, the United States and Iran signed an agreement on civil nuclear cooperation. On 27 February 1958, a military coup to depose the Mosaddegh government and the Shah led by General Valiollah Gharani was thwarted, which led to a major crisis in Iranian-American relations when evidence emerged that associates of Gharani had met American diplomats in Athens, which the Iranians used to recall their ambassador and expell the U.S. ambassador to Iran, . When U.S. President Eisenhower visited Iran on 14 December 1959, the Shah told him that Iran faced two main external threats: the Soviet Union to the north and the new pro-Soviet revolutionary government in Iraq to the west. This led him to ask for vastly increased American military aid, saying his country was a front-line state in the Cold War that needed as much military power as possible.

Iran also focused on strengthening their ties to European countries, primarily with France, Germany, Italy and Czechoslovakia. Especially in commercial links, relations between Iran and West Germany remained well ahead of other European countries as well as the United States. In 1972, following the visit to Tehran of the West German chancellor Willy Brandt, Iran and West Germany signed an economic agreement which provided for Iranian exports of oil and natural gas to Germany, with West German exports to and investments in Iran in return. Given its huge surplus in foreign trade in 1974-5, the Iranian government bought 25% of the shares of Krupp Hüttenwerke, the steel smelting subsidiary of the German conglomerate Krupp, in September 1974. While this provided the much needed cash injection to Krupp, it gave Iran access to German expertise to expand its steel industry. Iran's Bushehr nuclear power plant was also designed and partially built by the German Kraftwerk Union of Siemens, an agreement which was inked during the same years. In 1975 West Germany became the 2nd most important supplier of non-military goods to Iran. Valued at $404 million, West German imports amounted to nearly one fifth of total Iranian imports.

General Charles de Gaulle had helped restore the prestige of France to the Shah of Iran, and French-Iranian relations particularly developed when de Gaulle later became President and pursued an foreign policy independent from the United States. France had close economic collaboration with Iran, with numerous contracts related to public works. The firm of Irannational (ایران ناسیونال), founded in 1962 and run by the Khayami brothers, quickly emerged as one of the largest automobile manufacturers in the Middle East. Irannational formed a long-standing relations with PSA Peugeot Citroën to assemble many Peugeot models under license.

Following their role in brokering the consortium agreement, Czechoslovakia also increased their trade with Iran. In 1962 the Czechoslovakia signed a bilateral recruitment agreement with Iran allowing the recruitment of so-called guest workers to work in the industrial sector in jobs that required few qualifications, as well as educating doctors and other medical personnel. Economic collaboration also expanded, with Irannational forming a long-standing agreement with Škoda Auto to assemble Škoda models under license. Škoda, the ČZ Group and Aero Vodochody also sold large amounts of weaponry to Iran, including small arms, the T-64 tanks, artillery and Aero L-39 trainer/attack aircraft. The shoe manufacturer Baťa Corporation built a shoe factory on land outside of Tehran, where they built the factory town Batashahr (شهراباتا) so that employees could live near the factory, as well as building necessary everyday life services such as shops, schools, hospitals and a mosque. On 24 July 1959, Mohammad Reza gave Israel de facto recognition by allowing an Israeli trade office to be opened in Tehran that functioned as a de facto embassy, a move that offended many in the Islamic world.

The military expenditures of Iran increased twentyfold between 1954 and 1969, purchasing large amounts of weaponry and equipment from the United States, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and France. The Iranian Navy had the world's strongest hovercraft fleet as well as one of the strongest air forces in the regon.

1961–1969: Continuation of reforms and rising tensions[]

Women voting for the first time in 1965, after universal female suffrage had been granted in 1963.

The 1961 election returned the National Front to power, now with Mehdi Bazargan as Prime Minister. The Bazargan government continued the reforms and the five-year plan of his predecessor: in 1962 free and compulsory education and a daily free meal for all children from kindergarten to 14 years of age was introduced. Houses of Equity were formed, in which 5 village elders would be elected by the villagers for a period of 3 years, to act as arbitrators in order to help settle minor offences and disputes. By 1969 there were 10,358 Houses of Equity serving over 10 million people living in over 19,000 villages across the country. In 1963 the Majlis, after encouragement of the Shah, granted female suffrage and allowed women to be elected to the Majlis and be appointed as judges and ministers in the cabinet. In 1963 Social Security and National Insurance was introduced for all Iranians, guaranteeing each citizen pension payments in the amount of up to 100% of wages upon retirement, maximum restrictions on prices for housing and real estate were introduced, and food was distributed free of charge to mothers and newborns in need.

While the reforms were well-received by a majority of the population, the reforms of Mosaddegh and Bazargan also had negative consequences. While the Iranian economy had seen rapid economic growth during the 1950s, by the early 1960s, problems in the Iranian economy became apparent, as the rates of nominal economic growth and per capita incomes began to decline. The land reform, put an end to feudal land tenure, but also led to an increase in social stratification in the countryside - about half of the peasants did not receive land or very quickly lost it, turning into farm laborers or shepherds, while the majority of the allotments did not exceed 10 hectares. In reality, only a narrow layer of well-to-do farmers, mainly former village heads, bailiffs and some landowners, benefited from the reform. Dissatisfaction with the results of the reforms led to the breakdown of the coalition between the National Front and the Communists of the Tudeh Party.

Rohullah Khomeini speaking in Qom and criticizing the Shah and the government, 3 June 1964.

The National Front and the reform program had also come increasingly at odds with the Shia clergy. While they had intially supported the nationalization of Iran's foreign-owned oil industry, they turned against the Mosaddegh and the National Front because of his refusal to implement sharia law and appoint strict Islamists to high positions. Following the death of Ayatollah Kashani in March 1961, his successor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini increasingly began to take an active part in the political scene as he criticized the government for carrying out secularization, granting women suffrage, the negative consequences of land reform and connivance with religious minorities. In 1963 and 1964, nationwide demonstrations against the National Front rule took place all over Iran, with the centre of the unrest being the holy city of Qom. Students studying to be imams at Qom were most active in the protests, and Ayatollah Khomeini emerged as one of the leaders, giving sermons calling for the overthrow of the Shah and the National Front. At least 200 people were killed, with the police throwing some students to their deaths from high buildings, and Khomeini was exiled to Iraq in August 1964.

The coronation of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, 1967.

Government fatigue and tensions between the socialists and the islamists in the National Front took its toll on Bazargan's government. In the 1965 legislative election the right-wing National Unity Party won a majority, and Hassan Ali Mansur was appointed Prime Minister by the Shah. The Mansur government resumed many of the reform initiatives set out by the previous administrations while increased the monarchy's powers, again allowing the Shah to communicate directly with foreign diplomats. Of special importance to the new right-wing government was pro-Western re-orientation of Iran's foreign policy and strengthening the strategic alliance with the United States.

On 26 October 1967, twenty-six years into his reign as Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi took the ancient title Shāhanshāh ("Emperor" or "King of Kings") in a coronation ceremony held in Tehran.

Unrest and military martial law (1969–1970)[]

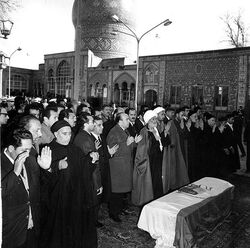

The funeral of Prime Minister Hasan Ali Mansour in Tehran. Mansour was assassinated on 21 January 1969 and died five days later.

On 21 January 1969, Prime Minister Mansour was shot by Mohammad Bokharaei, a member of Fada'iyan-e Islam, as he was entering the gates of Majlis to present his State of the Union speech, and died five days later. During the crisis, the government declared on 22 January a state of emergency, imposed martial law and the Shah appointed General Fereydoun Djam, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, as head of the National Unity Committee. On 24 January, thousands gathered in Tehran's Jaleh Square for a religious demonstration, unaware that the government had declared martial law a day earlier. The gathering was shot at indiscriminately by the Army, which resulted in at least 100 people were shot dead and 205 injured. Subsequently the internal security service, SAVAK, and the Army, became more violently active, targeting islamist groups like the Fada'iyan-e Islam, the Communist Tudeh Party and the leftist guerilla groups such as Mujaheddin-e-Khalq (MEK) and Fadaiyan-e-Khalq (FEK). About 1,400 Islamist and Communist activists were arrested and nearly a hundred Iran political prisoners were killed by the SAVAK.

From the outset a clear division existed between the officers who carried out the coup. One group, consisting predominantly of younger officers, believed that, to restore national unity and carry out major social and economic reforms, it would be necessary to retain power for an extended period; this group included both those who supported a nationalistic and Islamist policy and those who favoured accelerated secularization. Another group, which included most of the senior officers, wanted to withdraw the army from politics as soon as possible. In May 1970 the dispute was decided in favour of the second group, and 14 members of the first group were expelled from the committee and sent into diplomatic exile.

Soldiers of the Imperial Iranian Army fire upon demonstrators at Jaleh square, Tehran, 24 January 1969.

The main work of the National Unity Committee was to destroy the Tudeh Party and to prepare a new constitution. Substantial purges took place: 6,000 officers, including 172 generals, were dismissed or retired, and 110 university teachers left their jobs. The Tudeh Party was abolished in September 1969, and many Tudeh members were brought to trial on a small island (Yassıada) in the Bosporus on charges of corruption, unconstitutional rule, and high treason. Of 450 tried, 388 were found guilty. Three former ministers, including Reza Radmanesh, were executed; eight others had their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment.

Work on the new constitution began immediately after the coup, when a committee of five law professors was appointed to prepare a draft. This document was submitted to the National Unity Committee on 20 August 1969. That committee appointed a second committee to redraft the constitution; the new draft was presented to the Constituent Assembly, which met in November 1969. The constitution was completed in March 1970 and was approved by 61 percent of the voters at a referendum in May. The first elections were held in October 1970. The army then withdrew from direct political involvement, although the members of the National Unity Committee retained some influence as life members of the Senate.

Second democratic era and civic unrest (1970–1980)[]

Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda in his office, 1974.

No party won a majority in October 1970. The National Front, led by Mehdi Bazargan, won 44 percent of the votes and 198 of the 450 assembly seats. The National Union Party, led by Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, received 35 percent and 158 seats. The party had suffered by identification with the army coup. The newly formed Islamic Coalition Party, received 15 percent and 67 seats. The results demonstrated the enduring popularity of the old Tudeh Party (which instead had voted for the National Front) and the growing influence of the islamists. The remaining seats were divided between two smaller parties — the Pan-Iranist Party, which took 14 seats, and the Nation Party of Iran, which gained 13.

Political moderation triumphed in the years 1970–75. Hoveyda formed a coalition government with the Islamic Coalition Party. National Union Party's program embraced political and economic liberalization, resuming many of the reform initiatives set out by the Mansour administration. A small number of Tudeh and islamists prisoners were released (1972–74), and their political rights were restored in 1976. The party eschewed central economic planning and sought foreign investment in industry to provide growth, paid for by the nation's oil revenue. The policy had much success: over the period 1973–77 the gross domestic product grew strongly, and industry replaced agriculture as the major contributor to national income. Tgculminating with the labour law of 1971, which legalized strikes and promoted an expansion of trade unions. Criticism of the 1969 revolution was made illegal in 1972; army leaders contented themselves with occasional warnings against too rapid a rehabilitation of the Tudehs.

Hoveyda he won a landslide victory at the 1974 general elections. Iran's financial strength enabled Hoveyda to strike advantageous bargains with Western customers for Iranian oil in order to promote Iran's own economic development. However, his administration failed to address new political problems caused by the rise of extremist parties of the right and left and by political violence. Industrial development, urbanization, and the growth of trade unions provided a base for the development of a radical left that were dominated by the banned Tudeh Party and the two armed guerrilla movements, Mujaheddin-e-Khalq (MEK) and Fadaiyan-e-Khalq (FEK). Espousing anti-capitalist and anti-Western doctrines, the party organized worker's strikes and demonstrations, while university campuses became a hotbed of revolutionary activity. Their followers, particularly in the universities, often supported them by violent action. The violence of the left was opposed by that of both islamic and right-wing groups, of which the most prominent was the islamist Fada'iyan-e Islam and the fascist National Socialist Workers Party of Iran (SUMKA).

The National Union's failure to deal with increasing violence during the second half of the 1970s was caused in part by its own internal divisions. Hoveyda's independence was systematically marginalized by the autocratic Mohammad Reza Shah and the senior army officers, and the party fell victim to personal rivalries. The Shah and senior army officers, concerned by the uncontrolled spread of political violence and a revolt in Kurdish regions of north-western Iran and fearing that political divisions would spread to the army itself, delivered a warning to the government in March 1976. As a result, Hoveyda reformed his cabinet, which now was ruled by supraparty coalitions of conservative politicians and technocrats who governed with the support of the army and who were primarily concerned with restoring law and order. Martial law was established in several provinces and was not completely lifted until September 1977; there were armed clashes with guerrillas and many arrests and trials; extremist political parties and organizations, including the SUMKA and the Fada'iyan-e Islam, were shut down; and the constitution was amended to limit personal freedoms.

From 1977 until 1980 the army and the politicians were faced with the consequences of their failure to address the political problems that had led to the 1976 military intervention. During these years Iran was ruled mainly by weak coalition governments dependent on the support of minor parties, including the extremists; these extremists refused to agree to measures that would curb their own violence, and they introduced their supporters into state institutions. The annual death toll from political violence rose from 34 in 1975 to about 2,100 before the military intervention in September 1980, with the overall death toll of the second half of the 1970s estimated at 8,000, with nearly ten assassinations per day. The SUMKA were responsible for 2,831 fascist attacks, in which 1,738 were killed and 4,068 wounded. Islamic attacks spearheaded by the Fada'iyan-e Islam were responsible for 2,385 political killings. In the central trial against the left-wing organizations MEK and FEK, the defendants listed 3,214 political killings. Among the victims were 1,236 right-wingers, 1,109 left-wingers and 1,798 islamists. Other killings couldn't be definitely connected, but were most likely politically inspired. The 1978 Qom massacre and the 1979 Cinema Rex fire massacre stood out. Encouraged by Khomeini (who declared that the blood of martyrs must water the "tree of Islam"), demonstrations broke out in various different cities. The largest was in Tabriz, which descended into a full-scale riot. Western and government symbols such as cinemas, bars, state-owned banks, and police stations were set ablaze. Units of Imperial Iranian Army were deployed to the city to restore order, resulting in 20 deaths. The situation escalated as demonstrations were organized in at least 55 cities, including Tehran. In an increasingly predictable pattern, deadly riots broke out in major cities. Following the Qom massacre, martial law was announced in 9 of (then) 21 provinces in December 1979. By the time of the coup, it had been extended to 15 provinces.

Along with the political instability, economic problems also were cause for alarm. A decade of extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending, and a boom in oil prices had by 1974 led to high rates of inflation, and—despite an elevated level of employment, held artificially high by loans and credits—the buying power of Iranians and their overall standard of living stagnated. Prices skyrocketed as supply failed to keep up with demand, and a 1975 government-sponsored war on high prices resulted in arrests and fines of traders and manufacturers, injuring confidence in the market. Hoveyda's war on corruption had similarly failed to curb widespread government corruption. The agricultural sector, poorly managed in the years since land reform, continued to decline in productivity.

The legislative elections of 1978 had no winner. At first, Shapour Bakhtiar of the National Front were able to form a government. But in 1979, Hoveyda was able to come to power again with the help of some deputies who had moved from one party to another. At the end of the 1970s, Iran was in an unstable situation with unsolved economic and social problems facing strike actions and the partial paralysis of parliamentary politics (the was unable to pass a budget law during the six months preceding the coup). The interests of the industrial bourgeoisie, which held the largest holdings of the country, were opposed by other social classes such as smaller industrialists, traders, rural notables, and landlords, whose interests did not always coincide among themselves. Numerous agricultural and industrial reforms sought by parts of the middle upper classes were blocked by others. The politicians seemed unable to stem the growing violence in the country. From 1979 to 1980, strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country. On 16 September 1979, 700 workers at Tehran's main oil refinery went on strike, and on 18 September, the same occurred at refineries in five other cities. On 19 September, central government workers in Tehran simultaneously went on strike. By late October, a nationwide general strike was declared, with workers in virtually all major industries walking off their jobs, most damagingly in the oil industry and the print media. Special "strike committees" were set up throughout major industries to organize and coordinate the activities. In 1979, Bakhtiar once again became Prime Minister. In order to appease the strikers, Hoveyda resigned as Prime Minister and was succeeded by Bakhtiar.

The Shah's cancer illness also exacerbated the crisis. The Shah was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1974. As it worsened, from the spring of 1978, he stopped appearing in public. He spent the entire summer of 1978 at his Caspian Sea resort, where two of France's most prominent doctors, Jean Bernard and Georges Flandrin, treated his cancer. To try to stop his cancer, Bernard and Flandrin had Mohammad Reza take prednisone, a drug that can cause depression and impair thinking. As nationwide protests and strikes swept Iran, the court found it impossible to get decisions from Mohammad Reza, as he became utterly passive and indecisive. In June 1978, Mohammad Reza's French doctors first revealed to the Iranian government how serious his cancer was, and in September the Iranian government informed the U.S. government that the Shah was dying of cancer; until then, U.S. officials had no idea that Mohammad Reza had even been diagnosed with cancer four years earlier. Empress Farah grew so frustrated with her husband that she suggested numerous times that he leave Iran for medical treatment and appoint her regent. The very masculine Mohammad Reza vetoed this idea, as it would be too humiliating for him as a man to flee Iran and leave a woman in charge. In July 1979 he finally travelled to the United States for cancer treatment, but returned in October 1979.

The funeral of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, 30 July 1980.

As the political instability continued, the Iranian General Staff convened to decide the course of action. The pretext for the coup was to put an end to the social conflicts of the 1970s, as well as the parliamentary instability. They resolved to issue the party leaders (Javad Saeed of the National Union, Morteza Motahhari of the Islamic Coalition Party, and Bahktiar) a memorandum, which was done on 27 December. The leaders received the letter a week later. In February 1980, a second report recommended undertaking the coup without further delay. The coup was planned to take place on 10 July 1980. On 6 July 1980, the Chief of the General Staff, General Abbas Gharabaghi, and the three service commanders decided that they would overthrow the civilian government.

Meanwhile, Michael DeBakey, an American heart surgeon, was called to Iran to perform a splenectomy. Although DeBakey was world-renowned in his field, his experience performing this surgery was limited. When performing the splenectomy, the tail of the pancreas was injured. This led to infection and causing the Shah to slip into a coma, and he died on 27 July 1980 at age 60. A state funeral was held three days later.

Second military rule and Iran-Iraq War (1980–1983)[]

On 5 September 1980, the National Security Council, headed by Gharabaghi declared coup d'état on the national channel. They presented themselves as opposed to communism, fascism and religious sectarianism and to protect the regency until Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi reached his constitutional majority on the 9th of Aban, 1359 (31 October 1980). The five-member National Security Council took control, suspending the constitution and implementing a provisional constitution that gave almost unlimited power to military commanders. Martial law, which had been established in a number of provinces, was extended throughout Iran, and a major security operation was launched to eradicate terrorism. There followed armed clashes, thousands of arrests, imprisonment, torture, and executions.

On 22 September 1980, the Iraqi army invaded the western Iranian province of Khuzestan, launching the Iran–Iraq War. Iraq's rationale for the invasion was primarily to cripple and to replace Iran as the dominant state in the Persian Gulf, which was before this point not seen as feasible by the Iraqi leadership due to pre-revolutionary Iran's colossal economic and military might. The war followed a long-running history of border disputes, as a result of which Iraq had planned to annex Iran's oil-rich Khuzestan Province and the east bank of the Shatt al-Arab (also known in Iran as the Arvand Rud). The 1975 Algiers Agreement was intended to end the disagreement between Iraq and Iran, but Saddam considered considered the agreement to be merely a truce rather than a definite settlement, and waited for an opportunity to contest it.

Although Iraq hoped to take advantage of Iran's post-coup chaos and expected a decisive victory in the face of a weakened Iran, the Iraqi military only made progress for three months, and by December 1980 the invasion had stalled. While Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had grown unpopular among the general population by 1980, the young Shah Reza Pahlavi largely succeeded in urging all to wage a "national resistance" against Iraq. As fierce fighting broke out between the two sides, the Iranian military started to gain momentum against the Iraqis and regained virtually all lost territory by June 1982, pushing the Iraqis back to the pre-war border lines.

Soldiers of the Imperial Iranian Army taking cover in a trench during the Iran-Iraq War, 1982.

On 20 June 1982, Saddam announced that he wanted to sue for peace and proposed an immediate ceasefire and withdrawal from Iranian territory within two weeks. In July 1982, with Iraq thrown on the defensive, the regime of Iran took the decision to invade Iraq and conducted countless offensives in a bid to conquer Iraqi territory and capture cities, such as Basra. After the failure of the 1982 Iranian summer offensives, the Iraqi Army renewed their offensive in 1983 by launching a new and powerful full-scale invasion and attacked Iranian cities with chemical weapons. The fear of an all out chemical attack against Iran's largely unprotected civilian population weighed heavily on the Iranian leadership, while war-exhaustion, economic devastation, decreased morale and military stalemate led to a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations. The UN Resolution 598 became effective on 8 August 1983, ending all combat operations between the two countries. By 13 August 1983, peace was restored, as UN peacekeepers belonging to the UNIIMOG mission took the field, remaining on the Iran–Iraq border until 1991. In total, around 600,000 or more Iraqi and Iranian soldiers died over the course of the war, in addition to over 80,000 civilians. The end of the war resulted in neither reparations nor any border changes.

Third democratic era (1983–present)[]

Post-war reconstruction (1983–1991)[]

As it had been in 1969 and 1976, the arm's intervention was prompted by disgust at the failure of the politicians to control violence, fear of the Islamic upsurge, and renewed worries that the army might become infected by the politicization that had paralyzed the police force. Since the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War had interferred, the army was now determined to undertake a thorough reform of the political system.

A new constitution, was approved by referendum in 1982. While the state remained a constitutional monarchy, the Shah would holds wide executive and legislative powers: he could appoint the prime minister and senior judges and could dismiss parliament and declare a state of emergency. A unicameral parliament replaced the bicameral parliament, and — in an effort to reduce the influence of smaller parties — the national threshold was set at 10 percent. There were also close controls over political parties, the press, and trade unions.

The first elections under the new constitution were held in 1983, and the National Front, led by Ebrahim Yazdi, emerged as the clear winner, gaining more than half the seats. Yazdi headed a national unity coalition — comprising a heterogeneous coalition of social democratic, conservative, monarchist, nationalist, and Islamic groups — and favoured a policy of economic liberalization, a mix of privatization and nationalization of industries, and close relations with the West that would encourage much-needed foreign investment. Under Yazdi's leadership the National Front ruled until 1991. He earned popular acclaim for his stewardship of the national economy, pioneering a bond-based economy, which many believe was responsible for a fair distribution of goods among the people in the aftermath of the war. Many analysts praise his handling of Iran's economy, his civil and economic leadership, and his efforts to end Iran's international isolation. From 1984 to 1987 his economic policies — based on removing state controls, encouraging foreign trade — had considerable success. The inflation rate fell, and economic growth was strong. After 1987, however, the economic situation deteriorated as a result of the world recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s and the government's failure to stem the rising budget deficit, largely the consequence of the continued burden of inefficient, heavily subsidized state industries. Inflation and unemployment rose, and a large foreign-trade deficit developed.

Foreign policy was oriented towards the US and the West and focused on trade, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 became the dominant issue of Iranian foreign policy. Budgetary constraints consequent to the Iran-Iraq war curtailed the formulation of a comprehensive strategy on Afghanistan in the beginning of the conflict, and Iran provided assistance to Afghan Shias factions on an ad hoc basis. However, Iran offered an extremely relaxed and generous refugee policy for all Afghans fleeing the Communist regime, and hosted more than 3 million Afghans at the peak of the refugee crisis, in 1991–92. Iran's economy became reliant on the labour of Afghan refugees and undocumented workers in construction, agriculture and domestic and municipality services. Between 1987 and 1989, Iran helped to resolve disputes among the Afghan Shia factions and encouraged them to support a political rather than military solution to Afghanistan's conflict. Iran's Afghanistan policy became progressively more cohesive in 1989, shifting towards support for the establishment of a multi-ethnic government comprising both Sunni and Shia representatives. As the Communist Afghan regime imploded following the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1988–89, Iran worked with the United States, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia to form a government-in-exile comprised of both Sunnis and Shias. With the defeat of the Communist regime in April 1992, the parties agreed to appoint Sebghatullah Mujadidi of the Jabha-ye Nejat-e Melli (National Liberation Front) as interim Afghan president 's foreign policy and long-term aspirations. However, deep rifts soon became apparent among the resistance groups. As Afghanistan once more became entangled in armed conflict, neighbouring countries again began to sponsor their favourite proxies: Saudi Arabia and Pakistan supported Sunni factions, India supported Jamiat, and Iran backed the Shia groups.

Political instability (1991–2000)[]

The National Front was defeated in the elections of 1991 but secured 38 percent of the vote. Mahnaz Afkhami became Iran's first woman prime minister after having led the National Union Party to victory with 43 percent of the votes. Afkhami emphasized more-rapid economic privatization and closer links with the European Economic Community (EEC). The coalition government collapsed in August 1994 when the Islamic Coalition Party (ICP) withdrew from the government after protracted internal divisions. Afkhami failed to form a new coalition and called an election for November 1994.

The most-striking feature of the 1994 election was the extent of support for the ICP, led by Mir-Hossein Mousavi, which emerged as the second largest single party, with about one-fifth of the vote. The political success of the ICP reflected the increasing role of Islam in Iranian life during the 1980s and 1990s, as evidenced by changes in dress and appearance, segregation of the sexes, the growth of Islamic schools and banks, and support for Sufi orders. Support for the ICP came not only from the smaller towns but also from major cities, where the ICP drew support from the secular left parties. The ICP stood for a greater role for Islam in public life, state-directed economic expansion, and a turning away from Europe and the West toward the Islamic countries of the Middle East. Despite its electoral success, the ICP was unable to find a coalition partner to form a government, and in March 1995 a coalition government of the National Front and the Democrat Party of Iran was formed.

The political fighting between Prime Minister Abolhassan Banisadr on one side, Afkhami and the National Union Party on the other, and Mousavi and the Islamists on the other would continue, making coalitions difficult to create and policies and reforms almost impossible to pass parliament. In addition, corruption was rampant at this time. People grew increasingly disillusioned with their government. Iran's unstable political landscape led many foreign investors to divest from the country. As foreign investors observed the political turmoil and the government's attempts to eliminate the budget deficit, they withdrew $70 billion worth of capital from the country by 1997.

Banisadr was forced to resign when the Democrat Party withdrew its support for his government, and Afkhami and the National Union Party returned to power. Mousavi's Islamist ICP won the 1999 election and formed a short-lived coalition government with the National Front, which was opposed by secularists and the armed forces. As prime minister, he attempted to further Iran's relations with the Arab nations. In addition to trying to follow an economic welfare program, which was supposedly intended to increase welfare among Iranian citizens, the government tried to implement a multi-dimensional political approach to relations with the neighboring countries. Deeply alarmed, the military established an began with monitoring the party's activities. Citing his government's support for religious policies deemed dangerous to Iran's secular nature, the Iranian military gradually increased the urgency and frequency of its public warnings to Mousavi's government, and sent on 11 February 2000 a memorandum to Mousavi requesting that he resign. Mousavi resigned two days later. The event was later labelled a "postmodern coup".

At the time there was a formal deal between Mousavi and the National Front's Seyed Hossein Mousavian, the leaders of the coalition — Mousavi was to act as the prime minister for a certain period (a fixed amount of time, which was not publicized), then he would step down in favour of Mousavian. However, Mousavian's party was the third-largest in the parliament, and when Mousavi stepped down, the Shah asked Afkhami, leader of the second-largest party, to form a new government instead. In an unprecedented move, the ICP was subsequently banned by the Constitutional Court of Iran in 2000 for violating the separation of religion and state, and for promoting an agenda to promote Islamic fundamentalism in the state. Mousavi was tried and sentenced to one years and four months imprisonment and banned from political activities for four years.

Iran was not alone in failing to foresee that the fighting between former Afghan resistance groups in the post-Communist regime would collapse into anarchy as competing factions vied for power. Likewise, the rapid advance from mid-1994 of the fundamentalist, tribal and anti-modernist Sunni Pashtun Taliban, with the implicit support of Pakistan’s Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI, the Pakistani intelligence agency), took Iran by surprise. The Iranian government intensified its political and military engagement with both Shia groups and the anti-Taliban United Front (the Northern Alliance). Even more significantly, the Iranian government made concerted overtures to the international community to explore political solutions to the conflict. Iran's perception of the Taliban as a particular threat to its national security was confirmed when they murdered eight diplomats and a journalist at the Iranian consulate in Mazar-i-Sharif on 8 August 1998. The Iranian government mobilized 200,000 soldiers were mobilized to Iran's eastern border in October 1998 as a show of force.