| ||||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Palmyra | |||||||

| Language | Palmyrene Aramaic, Greek, Latin, various local languages. | |||||||

| Religion main |

Canaanite and Hellenic Polytheism | |||||||

| others | Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, various local religions and cults. | |||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||

The Palmyrene Empire is the name used by historians to refer to the regions under the control of the city of Palmyra during the late 3rd century and early 4th century (c. 270 - 313). Before its revolt, the oasis city enjoyed privileges very few other settlements in the late imperial period were afforded. In 260, the Sassanid king Shapur I managed to capture Roman emperor Valerian in battle. The Roman Empire splintered into multiple warring factions, though the Palmyrene king Odaenathus swore loyalty to Valerian's son Gallienus. Because of Palmyra's favored position, as well as a weakening of the central authority of the Roman Empire, Odaenathus was able to build a series of alliances in the east which challenged and expelled the forces of Shapur I. Under Odaenathus, Palmyra became the center of a quasi-indendent, but nominally loyal, faction of the Roman Empire.

In 268, Odaenathus died and Palmyra fell into the hands of Odaenathus' wife Zenobia, who ruled it as a queen regant for their young son Vaballathus. By force, she occupied Odaenathus' former allies and reunified his power base. She then named Vaballathus Augustus as well as Shahanahah, thus making Palmyra the head of a de facto independent realm. The death of Gallienus and subsequent short succession of emperors had weakened the Roman Empire such that Palmyra was able to take these regions relatively uncontested.

Following a decisive battle against Emperor Marcian of the Roman Empire at Byzantium, Queen Zenobia took advantage of the volatile situation in the Sassanid Empire and began a campaign into Mesopotamia, citing her late husband Odaenathus' reign over the region. By 284, the Palmyrene Empire had reclaimed Trajan's eastern border. These wars further decentralized the Sassanid Empire and were very costly to the Palmyrene Empire. Though they were successful, the revolt of the Theban Legion and rise of Christianity in the east shook Palmyrene stability to its core.

Further invasion by both the Romans and the Sassanids caused the region to fall into chaos. Palmyra was occupied along with the rest of the Levant and Anatolia in 309, ending the Palmyrene Empire. Though the kings would never again be styled as shahanshah, the Palmyrene Kingdom would be restored as a satrapy to the Sassanid Empire. Under the Komare dynasty, Palmyra would regain its status as an economic hub. Standing at the crossroads between a religiously-devided Persia, a Christian kingdom in Africa, and a Heliotheistic Roman Empire, Palmyra would become a religious battleground. However, the ruling Komare dynasty under Dacanathus would become intensely hostile to Christianity. An intense persecution followed, expelling most of the Christians from the city for decades. So great was the persecution that the Christians who survived were oftentimes Anchorites, while those who rejected the religion at the time of the Dacanathan Persecution were ostracized by those who refused to convert in a schism similar to the Donatist controversy of our timeline. In 319, Dacanathus died and was replaced by his brother Saballathus who converted to Christianity in 322. The already-radical Syrian Christians, whom had adopted very ascetic practices before the Dacanathan Persecutions, would form a hermetic sect of Christianity known as Aphrahatism. The Kingdom of Palmyra would exist as a client state of either the Kemetic Empire or the Sassanid Empire for centuries following its 3rd century apex, being the object of envy between the competing states.

History[]

Background[]

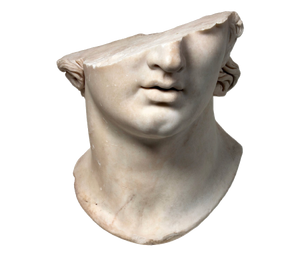

Bust of Odaenathus, King of Palmyra 260 - 267 AD.

Palmyra was an oasis city in Syria located in a key region of east-to-west trade. It was a wealthy city and it enjoyed privileges within the Roman Empire that most client states of Rome hadn't seen since the days of the Republic. By the 3rd century, the free city of Palmyra had remained a staunch ally of the Romans. The various crises that befell the Roman Empire spread from the west to the east, devastating Palmyra. The natural crises affecting the Empire softened the region up for an attack from the Sassanid Empire. The eastern Mediterranean became embroiled in a decades-long war culminating in the Battle of Edessa in 260, in which Emperor Valerian of the Roman Empire was captured by Shapur of the Sassanid Empire at Edessa. News of this shocking defeat utterly shattered Rome's control over the region. Odaenathus of Palmyra was forced to take matters into his own hands. He was declared King of Palmyra and began gathering an army to challenge the Persians.

Gallienus was able to dispatch the usurpers and granted Odaenathus a number of titles granting him effective and legal control of the east. These titles included "king of kings," frequently used by Persian kings. With his army, Odaenathus was able to deal a massive blow to the Sassanid Empire, ending their occupation of the region. In true Roman fashion, he pursued the Sassanid armies into their own territory in a series of punitive battles meant to discourage any further attacks. As the Sassanid Empire fell into a state of near-anarchy not unlike that of Rome in the 3rd century, Odaenathus made a name for himself as one of the few truly competent people remaining in the Roman Empire.

In 267, Odaenathus and his primary heir Hairan died. The circumstances and exact dates are unknown, but it is typically assumed that the two were assassinated. According to the notoriously unreliable Historia Augusta, the assassinations were carried out on the orders of Maeonius and backed by Odaenathus' second wife Zenobia, who wished for her sons to rule Palmyra, though this ancient source also suggests that Maeonius was the primary conspirator and was acting out of greed and depravity. The throne passed to Zenobia's eight-year-old son Vaballathus almost immediately, suggesting that Zenobia was with Odaenathus when he died. Though Maeonius also claimed the throne, he was captured and murdered almost immediately.

Zenobia ensured Vaballathus retained all the titles of his father. Because these titles were granted by Gallienus, they were recognized by his successors. Though there is little record written of what happened between 267 - 270 AD, it is clear Zenobia was ensuring the Kingdom of Palmyra and its supremacy over the region would continue.

Rise of Queen Zenobia[]

A painting of Zenobia surveying Palmyra, 1888.

The network of alliances held by Odaenathus were not inheritable by Vaballathus and, in light of recent victories by Claudius Gothicus, many formerly-rebellious provinces swore allegiance to his banner, though his sudden death threw the fate of the Roman Empire into question once more. The point of divergence from our universe occurred in 270 when Aurelian dies of plague. The new emperor Quintillus showed further ineptitude the next year, when an invasion force by the Juthungi reached the outskirts of Rome herself. Word of this alone was enough to prove to Zenobia that the time was right to send armies to re-secure allegiances with Palmyra through force.

Zenobia marched an army into Egypt in 271 to secure its grain supplies for Syria. The province had seen a cascade of disasters grip its large population, from famine to flood to the Plague of Cyprian. Its garrisons were not prepared to defend themselves and instead surrendered fairly peacefully. This was seen as an act of war in Rome, though there was presently very little the Roman Empire could do about it. Likewise, the Sassanid Empire was thrown into a miniature succession crisis following the death of Shapur I, meaning the Palmyrene eastern flank was secure for the time being.

To codify Odaenathus' network of alliances, Zenobia named Vaballathus Augustus as well as Shahanshah - king of kings. Her true ambitions are unknown in OTL, so we can only wonder if she wanted to place Vaballathus on the Romam or Sassanid throne or if she intended to carve out a new empire just for her son. Zenobia had also secured the loyalty of the Tanukhids following a brief conflict in 270. Syria was a melting pot of various ethnicities and creeds, and the Palmyrene Empire was to be an extension of this.

After securing Egypt, Zenobia ordered general Zabdas to march on Asia Minor, taking the coastal cities with some resistance. Palmyra had forced Cilicia into an alliance by the end of the year, then engaged Roman forces at Nicomedia in 272. The interior province of Cappadocia held out last. Garrisoned by Legio XV Apollinaris, the province surrendered in 273 after a brief fight as the provincial governor did not wish to risk weakening the border against Sassanid Armenia.

The riots in Rome and constant invasion of the borders required the constant attention of Roman emperor Marcian. In our timeline, Aurelian came to power during a very crucial period, and without a stabilizing presence, the Roman empire's schisms would have only grown deeper. The Gallic Empire had already lasted over a decade because the Roman Empire could not afford to divert its attention to the north. Without a clear and decisive blow such as the one delivered by Aurelian, the Palmyrene Empire would have remained as an independent power for much longer.

The Battle of Byzantium shattered the Roman army and secured Palmyrene independence.

It was not until 274 that Marcian could afford to launch an attack against the Palmyrene Empire. He commanded a numerically inferior army and held Byzantium. The fortifications there, which had long since been destroyed by Septimius Severus in 196, were reconstructed out of wood and refuse. The Romans were also protected by the natural geography of Byzantium. Marcian could not cross into Asia Minor without risking his position and Zabdas could not allow the amassed army to grow stronger at Byzantium. He ordered an assault on the city, risking and losing much of the Palmyrene army. His numerical advantage and tactical ability secured a victory against Rome.

Palmyra Ascendant[]

The Battle of Byzantium was so decisive not because of what happened during the battle, but what followed. Many expected the Palmyrene armies to launch further attacks into Greece and Thrace, and perhaps under more favorable circumstances they would have. Instead, the Palmyrene armies regrouped in Nicaea, unable to push forward without risking their position to the Heruli or to the Romans. Marcian, in the meantime, fell back to Thessalonika, which he used as an auxiliary capital for the rest of his reign. By the time this standstill ended, Palmyra was engaged in another fight.

Depiction of Palmyra as it may have appeared in antiquity.

This marked a true distinction between Zenobia's revolt and any other revolt from Rome. There were no true independence movements in the era. Any credible leader wanted one thing: to rule the empire. The Gallic Empire, though de facto independent, did not wish to be independent. It was merely a sustained rebellion which claimed its own line of succession, intending to one day march into Rome and become uncontested emperors. By not pursuing the Romans into Thessalonika, the argument can be made that the Palmyrene Empire truly became the first independence movement against Rome.

In 276, Hormizd I Kushanshah launched a revolt against his brother Bahram II of the Sassanid Empire. Though the resurgent Persian empire had made considerable victories in the past, the period following Shapur I's death saw the Sassanian dynasty fracture into rival sides. With most of his men fighting in the east, Bahram II left his western flank exposed, underestimating the fractured Roman imperium. He left his uncle Narseh in charge of this front, but he led a relatively small force overseeing Armenia. Zenobia, seeking to strengthen the border with Persia, invited the exiled Tiridates III to Palmyra. She offered to restore his position on the Armenian throne in exchange for loyalty.

The Roman Empire had been embroiled in civil war for decades, and the Persians did not expect an invasion on that border. In 277, the Palmyrene general Zosimus led an army into the ancient Armenian city of Carcathiocerta, taking it without much resistance. Towns and cities along the Tigris were sacked, providing the army with food and resources to continue its offensive. The hostile terrain of Asia Minor greatly impeded Zosimus and resulted in a temporary setback the next year when Narseh routed the Palmyrene forces at Ervandashat. Pursued by Sassanid forces, Zosimus retreated to Arsenias, where the Palmyrene forces were able to force the Persian armies to retreat. A large contributor to Narseh's trouble in expelling the Palmyrene armies boiled down to the lack of reinforcements from Bahram II. While the argument could be made that Bahram needed all the troops he could get, there is a very real possibility he was hoping Narseh would perish in the fighting.

Later that year, a Sassanid army threatened Nisbis, forcing the Palmyrene armies south while the Arsacid armies held the line in Armenia. Both armies were becoming exhausted by the end of the year. Neither were willing to commit to an assault in the mountainous terrain, the Sassanids were receiving minimal support, and the Palmyrene armies were not used to fighting in the mountains, contributing to their casualties. After defending Artaxata, the Palmyrene Empire halted its offensive for a time. Narseh attempted to dislodge the Armenian armies to little avail, and hoped to convince his brother to lend aid against the Palmyrene Empire. After receiving an insultingly-low number of reinforcement from Bahram, Narseh began to ask local kings for assistance. This came in the form of an attack by the vengeful Lakhmids.

A reconstruction of the Sassanid capital Ctesiphon.

As Vaballathus grew older, he exercised more power over Palmyra. Zenobia retained many of her titles, though she was no longer the sole person in command of the new empire. Sharing power with his mother into his adult life was seen as an embarrassment by some, and in 280 when the Lakhmids attacked, Vaballathus led the army in retaliation alongside Zabdas. This army trampled the Arab tribe and moved on to occupy Ctesiphon. This, along with Armenian offensive, forced Narseh out of the region. He would return at the head of an army in 284 to try to take Edessa. This time, Narseh fought on terrain favorable to both himself and Vaballathus. The heavy cavalry of Palmyra made the difference and again Narseh was routed.

To secure an alliance with the Arsacid Armenians, Vaballathus married Princess Khosrovidukht. In 285, she gave birth to a son - Septimius Timolaus. Named after the late son of Odaenathus, Timolaus' birth coincides with Zenobia's political sidelining. This may be due to influence by Khosrovidukht or, more likely, Vaballathus' coming of age and production of an heir. The empire, however, had seen most young emperors delve into unproductivity at best and violent insanity at worst. Zenobia still attended meetings of the boule and had a part in commanding troops for another several years until her exile in 292.

Vaballathus' capture of Ctesiphon could not have come at a worse time for the Sassanids, and the young emperor held a triumph in Palmyra. The boule named him Persicus Maximus. He declared that the land would fall under the governorship of Mesopotamia, as it had during the reign of Trajan. He would defend Ctesiphon from a Persian counteroffensive in 286, though the defense of the region became increasingly difficult later into the decade, as the Goths and Sarmatians made overtures into Asia Minor, requiring immediate attention.

The Sassanid Empire was forced to halt its offensive against the Kushano-Sassanian kingdom, resulting in Hormizd I Kushanshah retaining his independence from his brother. In our timeline, Carus similarly took advantage of the divided Persian Empire to launch a raid on Ctesiphon. In the world of Vastator Orbis, Vaballathus seems to be there to stay. The Sassanid Empire had a number of auxiliary capitals at the time, though the prospect of Ctesiphon not only being raided, but actually being occupied gave Bahram II pause in carrying on with his attack on the Kushano-Sasanian Empire. Generals were assigned to hold the eastern borders and Bahram returned west at the head of an army. In 288, a massive Persian counterattack retook Ctesiphon. Vaballathus attempted to defend the city at great cost, though his armies were forced to retreat along the Tigris.

St. Maurice & the Theban Legion[]

A depiction of St. Mauritius with the Theban Legion. After being proclaimed emperor by his armies, Mauritius would lead what would become the Kemetic Empire.

Alexandria, like Palmyra, was a metropolitan center of commerce, home to a wide array of peoples. At the time, Egypt was at the center of a growing movement of Christians and Manichaeans. This religion had faced persecution fairly recently at the time. While the Decian persecution had cemented martyrdom as a cornerstone of religious praxis, it had not specifically targeted Christians. The actions carried out by Valerian, however, certainly were. Furthermore, persecutions were carried out by Probus and Saturninus as a result of lower-class uprisings. While many Christians converted to save themselves and their families, there were some who evaded persecution, either due to secrecy or less-than-thorough efforts by local officials. However, the prospect of returning items and estates owned by Christians back to the state kept urban enforcers of these persecutions busy. Local persecutions continued after Valerian's reign and tensions between radicals on either side grew by the day. To add to this, Egypt had born the brunt of many of the crises of the 3rd century, especially plague and famine, their cities had been occupied by Palmyra, and still the resources the province so desperately needed were seized to feed the rest of the east. Many in Egypt did not approve of the reign of Zenobia and Vaballathus. The region was a powder-keg for insurrection.

In 285, Mauritius of Thebes was placed in command of the Theban garrison. As the Sassanids pressed an assault on Palmyra's eastern borders, the Lakhmids again revolted in favor of Bahram II. As much of the Palmyrene army was busy defending the border elsewhere, Vaballathus was forced to draw forces from Egypt to put the Lakhmids down. This coincided with a revolt of several nearby small Arab tribes. Mauritius was expected to launch an attack against the tribe, many of whom were Christians. Very few Lakhmids were involved in fighting and yet he was expected to exact heavy punishment on the tribes.

According to Christian hagiography, Mauritius and his armies mutinied, believing their order to attack other Christians to be just another bloody chapter in the persecutions. The historicity of this account is debated, as Maurice had gathered many non-Christian allies. It is possible he revolted for more material and worldly reasons. Vaballathus, furious, ordered the army decimated. The army instead marched to Alexandria, perhaps intending to gather allies in the city. The gates were opened and Maurice was allowed inside. There, he was proclaimed augustus. It is typically assumed he was not attempting to usurp the Palmyrene Empire and may have been an attempt at usurping the Roman Emperor. He had the support of many religious groups outside of the Christian faith, including Manichaeans, though the fact someone in Egypt was bold enough to rise to the occasion at this point was enough for many Hellenic polytheists to flock to his banner.

There are problems with this account. Most historians believe Mauritius was not yet Christian, or at the very least outwardly so. There is little historical evidence to support his adherence to the religion this early in his reign, but sources on his life before being proclaimed emperor are scarce and often fabricated. Historical accounts written well after the fact also draw familial links between Mauritius and Philip the Arab. This is also generally discounted. He faced turmoil within his reign almost immediately, and later that year a revolt of mint workers in Alexandria, which was put down in short order. Sparse references to trouble further down the Nile can be found, though details are unclear.

Up until this point, Palmyra had risen to each occasion to challenge a revolt. Egypt was an important food-producing province, but it was also a resource sink. During the war with the Sassanids, Vaballathus had made a name for himself and wanted to continue to portray strength to appear as the senior Augustus in the Palmyrene Empire. Zenobia believed it was important to hold this line and capture Egypt later, a sentiment which many of the forces fighting along the Euphrates shared. Vaballathus, however, was not willing to allow the province of Egypt to rebel. While he diverted a large amount of forces to quickly overwhelm Mauritius, Zenobia rallied a number of generals fighting along the Euphrates to hold the line and fall into a defensive position in preparation for a Sassanid attack.

Zenobia in Chains, statue produced late 19th-century depicting the exile of Zenobia.

Zabdas, a long-time ally of Zenobia, was sent to Egypt to put the rebellion down and ensure Zenobia's orders were being carried out. The 289 invasion of Egypt was absolutely disastrous. Mauritius' legion met Zabdas' army and was able to route the army, killing the general in the process. When word of this spread back to Palmyra, the narrative that Zenobia had sent her friend to die on purpose was spread around the city. This scandal, along with a number of long-standing rumors involving the death of Odaenathus, was the straw that broke the camel's back. Troops in her army loyal to Vaballathus mutinied and began to march on Palmyra, probably to murder Zenobia. To save his mother, Vaballathus ordered reinforcements to the Palmyrene city guard, putting down the rebellious legion. However, Vaballathus had been searching for a reason to remove her from her position altogether, and Zenobia was formally stripped of her titles. Heliotheist historian Lucio Attalus writes in his 5th century work that Zenobia stepped aside peacefully to avoid further bloodshed. Zenobia would live out the rest of her days in Beirut.

Vaballathus would never again be able to make an assault on Egypt. A massive Sassanid counterattack forced his troops out of Mesopotamia in 292, and an invasion by the Roman Empire into Asia Minor prevented him from retaking Egypt. The breakaway province would defend against a naval invasion by Maximian in 293 and would go on to take Carthage and Aelia Capitolina. These regions and their administrations saw a large influx of Christians, splitting the Roman Empire along religious lines and solidifying its fall. This Kemetic Empire would outlast the Palmyrene Empire by well over a thousand years.

Fall of the Palmyrene Empire[]

Government[]

Artist's depiction of Palmyra's agora with the tetrapylon in the foreground.

The evidence we have of the Palmyrene government largely comes from the imperial Roman era. The city of Palmyra was governed by a boule modelled after other Hellenistic cities. This was typically a body of 600 elites from various Palmyrene families which grew increasingly Romanized (but still distinctly Palmyrene) throughout imperial Roman history. Military leaders were appointed by this body and laws were proposed, though they were subject to review by the Roman provincial government. The boule was led by archons, which typically carried seniority vote and were considered leaders of Palmyra.

Palmyra was allowed a great number of freedoms compared to other cities in the empire. Palmyra's allegiance to Rome resembled those seen during the Roman Republic. Because it was considered a Roman ally rather than a proper member for quite some time, the Parthian Empire was willing to trade with it, making Palmyra an important nexus in trade. Under Caracalla, Rome granted Palmyra the status of colonia, further increasing Palmyra's ability to act independently from Rome.

A radical shift in Palmyra's government began with Odaenathus, who assumed an autocratic position over the city. He was styled as ras or "lord" of Palmyra and was given the rank of legatus of Phoenice in the empire, tying the Palmyrene army with that of the province. This political sway was what allowed him to build his power in the first place. Following the collapse of the Palmyrene Empire, the title of ras was used for the lord of Palmyra for centuries to come. The title of archon or duumviri is no longer extant in Palmyra following his reign. Following his declaration of monarchy, Odenaethus appointed a governor to oversee the city of Palmyra.

Following Odaenathus' death, Zenobia again dramatically changed the structure of the city when she emulated the Palmyrene monarchy to resemble that of imperial Rome. Vaballathus and Timolaus would style themselves as both augustus and king of kings. The boule became a senate and Vaballathus would revive the office of duumviri as consul, naturally with Zenobia serving in her position as consul until her son reached adulthood. The Palmyrene senate was not interested in engaging in the affairs of others cities and were reluctant to open the city to further Greek and Latin influence. This allowed the Palmyrene emperors to enjoy virtually unchecked political power.

Zenobia relied on the army to keep the Palmyrene Empire stabile, meaning the politics of the legions were ultimately the politics of the Palmyrene Empire. After the Battle of Byzantium, Zenobia placed three generals in charge of overseeing assigned groups of provinces under military control. These districts were called Praetorian Eparchies and the generals overseeing them were named praetors. These offices would become adopted in the west in the 4th century.

Four Tribes of Palmyra[]

Pre-Roman Palmyra had tribal origins and much like the patrician families of Rome, connections to these founding tribes was important to one's political career. This was retained to a certain degree into the 3rd century, though the rise of Odaenathus' family led to this equilibrium disintegrating by the early 4th century. Inscriptions with the Bene Maazin family exist dating from the 7th century and a noble family from Beirut during the medieval period claimed descent from the Bene Komare.

- Chomarenoi/Bene Komare: A priestly family sharing a cognate with the Hebrew Cohen. Associated with Malakbel.

- Bene Maazin: An originally-nomadic Arabic tribe with a large trading presence in the region, associated with Baalshamin.

- Bene Mattabol: A western tribe noted for frequent feuds with Bene Komare. Its priests typically served the fertility goddess Atargatis.

- Claudius: Inscriptions refer to a fourth tribal family with western ties. Whether they were Romans themselves or the name is a Romanization of a Palmyrene tribe is unclear and much of their history is lost to time.

Egypt was the first of these administrations, with Septimius Zabbai leading it. The administrations of Syria Coele, Syria Phoenice, Syria Palestinia, and Arabia were rolled into the Eparchy of Anatolis (east in Greek). This word was used interchangeably with the Syriac madnkho, and the term would again be used by Christians as Mizrah, which would become a common name to describe the entire Middle East. The last administration was Asiana, controlling the entirety of Asia Minor. Its capital was Ephesus.

Kings of Palmyra[]

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odaenathus |

c.260 - 267 (Roughly 7 years) |

Proclaimed himself emperor shortly after the Battle of Edessa. Ruled alongside his son Hairan who died around the same time. |

c.220 - 267, assassinated, possibly by his nephew or even by Zenobia herself. | |

|

Vaballathus |

c.267 - 24 January 294 (Roughly 27 years) |

Succeeded his father, ruled with Zenobia until 289. Also styled king of kings and augustus. |

c.259 - 24 January 294, died in battle against Narseh. | |

|

Zenobia |

c.267 - 18 July 289 (Roughly 22 years) |

Succeeded his father, ruled with Vaballathus until 289. Also styled augusta. |

c.240 - 1 June 307, died in exile in Antioch. |

Military[]

Being situated between two rival empires in a lucrative position along trade routes, Palmyra had a strong, martial culture. Its armies were frequently used to defend the eastern stretches of the Roman Empire. Depictions of the exploits of Palmyrene soldiers can be found in iconic reliefs around the empire, most famously on Trajan's column. Palmyrene forces were instrumental in many of Rome's wars with the Parthian empire, and if they were not being led by the emperor to strike against Rome's enemies, the Palmyrene armies formed a cornerstone of the Limes Arabicus. This prowess is what allowed Odaenathus to expel the Sassanid forces from the Roman Empire. While Palmyra owed its prosperity to trade, it owed its position in power to its mighty legions and a large sum of mercenaries.

Religion[]

The Temple of Bel as it appeared in our timeline prior to its destruction in 2015 by ISIL. Malak-bel was the head of the Palmyrene pantheon.

Syria was a cultural melting pot before and during the time of the Roman Empire. It was the crossroads of many different empires throughout history and was home to a number of religious movements. The peoples of Syria practiced a multitude of both old and new religions, making Palmyra a vibrant city with various temples to various deities from a myriad of different pantheons. While most people in Palmyra prescribed to a hybrid of Semetic and Roman cults, many monotheistic religions were practiced in the city. There were temples to Babylonian, Levantine, and Arabic deities in Palmyra. Additionally, a number of monotheistic religions had either taken root or originated entirely in Syria.

Naturally, there was something of a divide between the followers of established religions and those following new religions. Most of the aristocracy practiced Hellenic or Hellenized Aramean faiths while Christianity became increasingly favored by the lower classes in Palmyra. There are not any recorded interactions between Christians and non-Christians in Palmyra prior to 270. The city was also home to worshippers of Elagabalus, a solar deity analogous to Helios or Sol Invictus. Many historians believe Aurelian adapted these cults when he named Sol Invictus as Rome's primary deity in OTL. For this reason, Sol Invictus has oftentimes been named a separate deity from Helios or Sol. However, many modern historians have begun to assert that these deities were one in the same. Furthermore, the emperor Elagabalus introduced this cult to Rome decades prior. Vastator Orbis therefore assumes the trajectory of religion in the Roman Empire was pointed towards adopting a central solar deity.

Bel and the Trinity of Baalshamin[]

Limestone relief from Palmyra depicting the moon god Aglibol, the supreme god Baalshamin, and the sun god Malakbel (left to right). The Roman style of armor should be noted.

The majority of Palmyrene people worshipped a Hellenized variant of Aramean polytheism. Though many of these deities had been worshipped in Palmyra for centuries, the city assigned unique characteristics to these deities. These figures were further transformed by centuries of Greek influence under the Seleucid and Roman Empires. The chief diety worshipped in Palmyra was Bel. The word 'Bel' was an honorific in Syriac meaning "lord" and had been the name of Palyra's central deity since the 3rd century BC. This is similar to how "deus" or "god" evolved from a title to the accepted name of the Christian god.

Bel was one of two primary deities in Palmyra, Baalshamin being the other. Both shared similarities but did not appear to be mutually exclusive. They were lords of heaven and wielded thunderbolts. They were synonymous with Zeus and Jupiter in the Roman world, Ahura Mazda in Zoroastrianism, and Yaweh in Christianity and Judaism. They also existed in a trinity with Malakbel and Aglibol, gods of the sun and moon respectively. Temples to each divinity could be found throughout Palmyra, with shrines to each in the Temple of Bel.

Also occasionally in this trinity (especially in cases where Bel and Malakbel are treated as one in the same) was Yarhibol, god of justice. There were roughly sixty ancestral gods of the families of Palmyra. These deities acted as personal gods (Gads) for their respective members. Because of this, the priest caste was typically the highest in Palmyra, as they were all believed to be descended from gods. The ancestry of important political families also frequently traced back to Gads.

Bel is typically identified with similar solar deities in the Roman and Persian realms. The god is synonymous with Ba'al, a sun god which appears in many different forms throughout Syria. Due to hostilities with the Parthian and the later Sassanid Empires, the Roman Empire maintained a constant presence along the border, resulting in the adoption of many of these solar cults by the soldiers stationed there. This includes the worship of Elagabalus/Helios which some barrack emperors espoused in the later Roman Empire. Another notable example is the mystery cult of Mithraism, which spread throughout the Danube and Rhine provinces. By the late 3rd century, much of the soldiery had been exposed to some form of solar cult one way or another, making the transition to heliocentric paganism in Rome a much easier process.

Adherence to the Cult of Bel waned in Syria after the 4th century. Persecutions in the 5th century followed, and many temples were converted to cathedrals, including the main temple in Palmyra. Bel would survive as a figure in syncretic faiths such as Manichaeism and the Roman solar cult would preserve Malak-Bel. A small minority of adherents to Palmyrene polytheism would exist in some shape or form for centuries.

Christianity and Judaism[]

Syria was the birthplace of many religions, though very few had as much impact on world history as Judaism and Christianity. The Kingdom of Judah had a marked impact on the region in the 9th and 10th centuries BC and, according to the Hebrew Bible, Palmyra, known locally and to the Jews as Tadmor, had been founded by Solomon of Israel. This is highly disputed by historians. It can be assumed there was a Jewish community in Palmyra as of the point of divergence from our timeline due to inscriptions in the Palmyrene language exist in the necropolis of Beit She'arim.

Jerusalem itself had been all but destroyed in 70 AD and Jews were banned from the city, resulting in a Jewish diaspora, especially throughout Syria. This led to the growth of the Jewish community in Palmyra. In our timeline, the city would become a haven for Jews well into the era of Islam. Jewish tribes and communities could be found all over Syria, many of whom faced persecution following the rise of Christianity. Jerusalem was renamed Aelia Capitolina under Hadrian and the decree banning Christians and Jews from the city remained until the Sassanid Empire captured the city in the 4th century.

Evidentially, many Jews supported Rome over Palmyra. Leading rabbi Johanan bar Nappaha was quoted in the Mishnah saying, "Happy will he be who sees the fall of Tadmor." Though this does not speak for all contemporary Syrian Jews, Johanan bar Nappaha was a leading Jewish figure in the region. His role in compiling the Jerusalem Talmud means he played a central role in contemporary Jewish politics, and his opinions on the matter are quite interesting, especially considering typical Jewish opinion of Roman occupation. This paints a picture of what local politics in Syria was like during the time of the Palmyrene Empire. Many of these cities were established powers retaining an identity well into Roman occupation, and the oasis city of Palmyra was a relative newcomer to power.

As a Syrian city, Palmyra likely would have been home to many Christians. Indeed, Syria and Egypt, both of which were under Palmyrene control, were hotbeds of Christianity. Many of our best sources of the crisis of the 3rd century come from Christian writers, particularly Cyprian of Carthage and Dionysius of Alexandria. Christian discourse at the time allows us a glimpse at the turmoil in the Roman Empire other sources tend to glance over. At the same time, they depict a grim populace convinced of apocalyptic prophesies. Many believed the end of the world was at hand, and given the events of the period they cannot be blamed.

The east had been the target of the Decian persecution in 250 AD, which had specifically targeted Christians in 257 under emperor Valerian. During this period, Fabian, bishop of Rome, set an example of martyrdom. This powerful act of self-sacrifice became a cornerstone of Christian praxis and would heavily influence their actions during times of persecution throughout the world, both in our timeline and in that of Vastator Orbis. Persecutions after the point of divergence in both universes would take place under different circumstances, though in the Vastator Orbis timeline the persecutions could only target Christians in Italy, Greece, and Gaul. Vaballathus attempted to ally himself with Christian leaders to prevent a fifth column from rising in the Palmyrene Empire, though following the revolt of Maurice and the Theban Legion the Palmyrene Empire adopted an anti-Christian policy.

Other Faiths[]

|

Timeline of the Fifth Century

|

|

Britannic Empire Palmyrene Empire Bagaudae |

Rome in Late Antiquity Imperial Cult |

Kemetic Empire List of Kemetic Emperors Kemetic Christianity Katholicos of Carthage Alexandria

|

|

Zoroastrianism Manichaeism |

Armenian Empire Armenian Christianity Katholicos of Armenia Cathedra of Babylon

|