Pro mundi beneficio | |||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Ciudad de Panamá | ||||

| Other cities | Colón | ||||

| Language | Spanish, Portuguese, English | ||||

| Government | International territory administered by South American Confederation | ||||

| High Commissioner | |||||

| Area | app. 4,500 km² | ||||

| Population | approx. 300,000 | ||||

| Currency | Peso Real | ||||

The story of the Panama Canal Zone since Doomsday is the story of today's world order. Traversing the most strategic 40-mile stretch on the planet, the Panama Canal has, more than any other place or issue, shaped relations between the world's major powers. Cooperation and conflict, violence and triumph have shaped the Canal Zone in different portions at different times. The canal brought the world dangerously close to a great-power war. Its peaceful conclusion laid the groundwork for the friendly world order promised by the League of Nations. Its governance became the model for other international territories. Today, the CZ is administered by a commission of the South American Confederation, although the League of Nations also has some supervisory role there. While the SAC reaps the profits from canal trade, it is obligated by treaty not to discriminate against ships by nationality, except in cases of war, and in case of South American and French ships, which have special rights in the canal stemming from earlier treaties.

1983[]

American troops had begun to withdraw from the Panama Canal Zone after the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaty, and in 1979 the United States ceded the Canal Zone to Panama. But six years later, the US still operated the canal itself, and its military presence remained substantial, especially at Fort Clayton and Howard Air Force Base, both near Panama City. Howard was the headquarters for all US operations in Latin America, making it a major target in the Soviet nuclear barrage.

| Permanent members | |

| Members until 2023 | |

| *High Commissioner |

Panama was struck by an MR-UR-100 "Spanker" missile with a total MIRV destructive strength of 1.6 megatons divided among 4 warheads. All four scored direct hits on American military targets. Howard AFB was wiped out, as were Fort Clayton and Fort Amador across the canal. These blasts obliterated Panama City's Balboa district, and the entirety of the city experienced blast and thermal damage. Some 50% of the urban population perished immediately, with more dying later from radiation, flooding, and shortages resulting from the attack. The fourth warhead struck Fort Sherman on the Caribbean end of the canal, breaking glass and causing severe burns throughout the city of Colón.

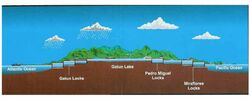

The warheads also did severe damage to the canal itself. The Miraflores Lock, nearest the city, was completely destroyed, and the Pedro Miguel Locks were damaged. The Gatun Locks near Colón received only very light damage. Released from its locks, the Pacific side of the canal began to drain into the ocean. The ruined city was badly flooded.

The attack found the Panamanian government in an unstable state. Manuel Noriega, head of the armed forces, had seized control of the government in August 1983 but was not yet firmly in power. No authority in Panama was strong enough to stem the chaos and looting that broke out after the attack, and there was no one to prevent the flooding that followed nor to clean up the damage. Panama City was soon a swamp, and the Republic of Panama did not take long to descend into total anarchy.

Aftermath[]

Cross-section of the canal showing the locks and their elevations

Surviving American troops did what they could to flee to higher ground and carve out a pocket of order. But armed Panamanian groups, some of them ex-military, opposed them. The Americans were also soon torn by factions of their own, with many choosing to cross the isthmus to make their way out of the country. Many ended up in American territory in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Those troops that remained were soon indistinguishable from the other guerrilla groups fighting for advantage in the countryside. Together they further destabilized the Panamanian state and extinguished any semblance of national unity.

Refugees from Panama City mostly headed eastward, toward the Darién rain forest region, where they settled in a string of dismal camps at the forest's edge. Colombia feared that their presence would aggravate the situation on the other side of the border, where numerous rebel groups threatened to destabilize the nation. The last thing Colombia wanted was for the Darién to become a rebel stronghold. Colombian troops were in Darién before the end of the year, cooperating with the Kuna tribal government to regulate and defend the camps.

Colombia's President Belisario Betancur negotiated a peace with the major rebel groups in 1984, and by 1985 they were participating in a unity government. Before long, Colombians were talking about Panama. It had once been Colombian, after all, and now it was a failed state. If they restored order there and re-opened the canal, it would benefit the entire region.

Meanwhile, the situation on the ground in Panama was in flux. Noriega had survived the first attack but was certainly dead by 1985, depriving the remnants of the army of their natural leader. The Americans, still the strongest military force in the country, had begun to leave in greater numbers by 1986. Rumors had begun to circulate that a surviving US contingent still existed out in the Pacific, and many soldiers attempted to cross the ocean in anything remotely seaworthy. Those that remained faced more pressure from Colombian forces on the edges of Darién, and most Americans still in Panama crossed to the west side of the canal before 1988.

Colombian Intervention[]

In 1986, late in Betancur's term, Colombia sent a team of military scouts to explore the canal's course, determine the damage, and inform the government whether rebuilding and re-opening it was feasible. The verdict: Locks were severely damaged on the Caribbean as well as the Pacific side, due to the guerrilla fighting. However, the channel itself remained intact. Radiation in the swamp around Panama City remained a hazard but was slowly dissipating. Rebuilding the canal would require a huge financial and military commitment from Colombia... but it was probably worth it. A restored canal would link Colombia's two coasts and improve commerce throughout South America. Colombia should take steps to secure the Canal Zone as soon as possible - before anyone else could.

It took three years for Colombia, now under the administration of Virgilio Barco, to begin carrying out this plan. In the meantime, it was increasing its presence in Panama, at least in the Darién. Colombia and the Kuna together created the Darién Regional Authority in 1988 to govern the refugee camps. Thanks to Colombia, part of Panama was peaceful again. In Colombia itself, cooperation with Venezuela revived the economy and kept the government solvent.

The success of the agreements with Venezuela convinced President Barco, never an enthusiastic free trader, to modify his views and make trade a priority. In a speech in 1988 Barco said that re-opening the canal was vital to Colombia's economic well-being. In 1989, Congress finally appropriated some money to rebuilding the Panama Canal.

Military action had to come before any rebuilding, however. Colombian troops established a beachhead near Panama City and another near Colón in 1988. Their objective was to secure control of the CZ from each direction. From its own civil war and its actions in the Darién, Colombia had learned how to cooperate with local armed groups in order to secure a region. A number of guerrillas were paid off to defend, rather than attack, Colombian-controlled areas. Nevertheless, it was a tough slog. The troops had to resort to naked displays of force more than occasionally. Casualties were high, especially among the local darienitas hired as auxiliaries. Militia groups proved unreliable, and Colombian troops often had to secure the same area more than once.

Soon, the Colombian government realized the work was too great to take on alone. Venezuela and Ecuador had both offered to cooperate in the project. At first Colombia had not wanted to give up sole control of Panama, which it regarded as a lost province. But the job was simply too big, and too many Colombians were dying. In 1990 the new Colombian President, Luis Galán, invited Venezuelan and Ecuadorian army troops to join the Colombian complement. Still, it was another year before any construction work could be done, and even then the entire length of the canal was not completely secure.

Engineers first came to Panama in 1991. The first area of focus was the Gatun Locks, on the Caribbean side. Fort Sherman's location at the end of a promontory meant that the warhead there had mostly spared the canal and locks, though guerrilla fighting in the late 80s had caused further damage. Work also began clearing debris from the abandoned city of Colón. Work on the Pacific side, where nuclear damage had turned Panama City into a wetland, took longer to get underway. When an American ship, the USS Benjamin Franklin landed near the ruined city in 1991, its explorers encountered the small Colombian outpost but saw no signs of rebuilding. The log simply reports the canal as "impassable". When Colombian officials met with the Franklins crew, they made no mention of their project, fearing US meddling. Their fears proved well founded.

International Conflict[]

It was almost a decade before another major worldwide expedition by American, Australian, or New Zealand ships (and after that, exploration was regularized with the creation of the WCRB.) However, many small voyages explored the west coast of the Americas throughout the 1990s, most of them leaving from Hawaii, which had recently been restored to democratic government. One such mission was sent in 1994 to do a more thorough survey of the Canal Zone. This time, they discovered the South American reconstruction project, which was now doing work in the channel on the Pacific side.

The American Provisional Administration and its allies did not respond right away. George Bush, President of the APA, was certainly ambivalent about intervening in Panama; it was hard enough to maintain U.S. control in Hawaii and Alaska, and the administration's top priority remained the dream of reestablishing a presence on the American west coast. Australia and New Zealand were also not prepared to get involved; Panama seemed too distant, and the project too unlikely to succeed.

But as work progressed, many began to see Panama as vital to their geopolitical interests. Australia and New Zealand's increasingly close and powerful union was helping to foster a wider outlook, and a restored canal could the door to commerce and influence in the Caribbean and Atlantic worlds. In 1996, the new Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand sent a message to Bogotá asserting that it had a stake in the restoration and governance of the Canal Zone. The legal basis for this claim was that when the American Provisional Administration dissolved, the ANZ Commonwealth took on its diplomatic commitments in the Pacific Ocean, which it now defined to include the CZ. And under the ANZC's interpretation of the 1977 treaty, the Canal Zone was to remain permanently neutral; the South American powers had no right to take it over unilaterally.

The claims were dubious: both parties to the treaty in question, Panama and the United States, had ceased to exist as coherent nation-states. It was far from clear what power, if any, had a legal claim to the canal. Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador mostly ignored ANZ's assertion. They had got to Panama first and were investing a great deal into it.

The conflict proceeded slowly. The ANZC was in no position to take the Canal Zone by force; not yet, anyway. Critics claim that it now planned to let the South American nations spend the money on rebuilding, only to swoop in and seize it after its completion. Whether the ANZC inner circle actually made this calculation is still a mystery. At any rate, it did nothing more for several years.

Meanwhile, another major power entered the Central America region. In 1997 Socialist Siberia, the successor to the Soviet Union based in Krasnoyarsk, sent an expedition of its own around South America in order to make contact with its old ally Cuba. Before long, Siberia and Sandinista-run Nicaragua also formed an alliance, and it actively began to support the Sandinista Party in Costa Rica, which captured the presidency in 2000. Siberian merchant ships quickly began a lively trade in the Pacific, and the country now had a strong interest in having easy and reliable access to the Panama Canal.

Finally, the United States Atlantic Remnant, based in the Virgin Islands, considered itself, not the APA or ANZC, to be the signatory nation to the Torrijos-Carter Treaty. Unlike Australia-New Zealand, the Atlantic Remnant realized that it had no chance of seizing the Canal from the South Americans. Its policy was to consider the South Americans successors to Panama and therefore its policy was to claim rights only before 1999, after which it would have no further stake in Panama. Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador welcomed USAR cooperation and even enlisted its help in defending part of the coastal area west of Colón. The USAR still maintains a contingent there, since 2000 as paid mercenaries.

Operation[]

South American crews continued to repair the canal. Work on all three major locks was finished in 1998; then hydrological work began to drain the swamps and fill the channel with water again. Meanwhile, Colombia took steps to increase its control over the rest of Panama. The Darién region, under the name Darién-Kuna-Emberá, had been organized into an autonomous state under Colombian protection in 1991. In early 1999, after a referendum, Colombia annexed the region outright. Soon after, Congress officially claimed all of Panama except the CZ, which it would have to share with Venezuela and Ecuador. An act of Congress created the "East Panama District" between the Darién frontier and the CZ, which it authorized the military to pacify by force. An expedition in 2000 failed completely, but Colombia was committed to reconquering its old province.

On May 1 of that year, the South American allies declared success. Colombian President Andrés Pastrana rode a ship with the Presidents of Venezuela and Ecuador from Colón to Panama City to celebrate the canal's completion and inaugurate a new era of South American control of the shipping lanes. It was a tremendous achievement for all three nations and a time for celebration. The tasks of conquest and reconstruction were over... now began the still greater tasks of defending the canal and putting it to good use.

Defending the Canal Zone remained a challenge. Several militia groups placed in charge of defending parts of it were still there in 2000, and they were demanding shares of the money that they knew would soon be pouring in. Like the ancient Romans, the South Americans feared their border guards as much as they feared the enemies beyond the border. Often they had little choice but to give in to their demands. Defending the CZ would continue to be a financial drain.

French Connection[]

Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador were immediately bombarded with requests for favorable access to the canal. Brazil and Argentina, the trading powerhouses of the continent, were especially insistent. So was a new nation on the scene: the Republic of the French Southern Territories. In 1999, the surviving French territories in the Pacific - French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, and New Caledonia - had formally united in what they hoped would be the first step toward restoring the French Republic. The French islands in the Caribbean - Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthélemy - were intermittently in contact with their co-nationals in the Pacific. As soon as the Canal was in operation, the islands' joint government, the French Antilles, voted unanimously to join up with them as soon as possible.

Representatives from the French Antillies approached Colombia seeking help. For seventeen years they had scrupulously resisted political encroachment by both the South American countries and the English-speaking East Caribbean Federation, all in the hope of eventually reuniting with a restored France. Now the opportunity had finally arrived, but the Pacific and Caribbean islands, together with Reunion and Mayotte in the Indian Ocean, could not communicate without cheap and open access to the Panama Canal.

Colombia, and its allies, granted special privileges to the French, but extracted significant economic advantages in return. Their ships obtained favorable trade terms not only in Martinique and Guadeloupe, but in Tahiti and New Caledonia as well, extending South American trade out into the Pacific. French ships could use the Panama Canal for practically nothing, but the new Republic had to adopt strict registration rules so that others could not use the French flag to avoid paying customs. The deal made the new world-spanning French republic possible, and it created close bonds between it and South America. Since the Pacific islands already had close relations with the ANZC, the canal treaty put the French republic in a strong position to act as a neutral arbiter between them.

Toward War[]

2000 was also the year of Australia-New Zealand's second major worldwide expedition. The ANZS Carl Vinson, a former American aircraft carrier, followed the route of the Franklin, anchoring in the Gulf of Panama after sailing down the coast of North America. This time, however, this course seemed far more threatening. A party was allowed to to speak at the end of a pier with the military commander in Panama City, but a dispute arose when he refused to allow the ANZ officers either to land or take a boat up the canal. The argument became heated. A shot was fired. The ANZ crew returned to their ships without returning fire. The Vinson bypassed Colombia and Ecuador and sailed on to Lima.

Relations between the ANZC and the canal powers just got worse from there. In 2001 the canal was opened to commercial traffic. Because of the dispute, ships registered in Australia and New Zealand were specifically excluded. This was a clear violation of the Panama Canal Treaty of 1977, and the idea that their ships would be essentially cut off from the Atlantic was unacceptable to commercial concerns in Australia and New Zealand. Most of the people agreed with them. On the other hand, many voices on both sides of the Atlantic continued to urge de-escalation. The presidents of Chile and Peru criticized Colombia's confrontational stance and sought ways to cooperate rather than compete with the ANZC.

In 2003 the ANZC dispatched a naval squadron to Panama. This expedition was even more provocative than the last: it not only anchored in the Gulf, but marines effected a landing on the Pearl Islands, which were not under any government's effective control and thus were undefended. Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela put their own forces on alert. Australia-New Zealand withdrew after a few days. The latest show of strength did nothing to change the stance of the three canal powers. Its major effect was to turn public opinion sharply against the Commonwealth all over South America.

The Australia-New Zealand superstate had alarmed South Americans since it had come to be eight years earlier. Its intimidation tactics only confirmed the common assumption that the Commonwealth was merely the latest incarnation of the infamous Anglo-American imperialism. The incident galvanized the South American nations into going forward with plans for a military and economic alliance of the entire continent. Whereas before the attack several countries had refused to discuss the alliance until certain issues were resolved, afterwards they had no choice but to bow to the people's demands. Diplomats and presidents met in May 2004, and on June 2 they declared the formation of the South American Confederation. The status of the Panama Canal was one of the issues discussed at the first meeting. It was agreed that control of the Canal Zone would be handed to the SAC at a future date, but that Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador, as the canal's builders, would have guaranteed seats on a five-seat commission to govern it. This model would later be adopted by the League of Nations for administering its international territories.

The following year, the ANZC tried again. This time it reached out to the other major power that stood to benefit from open access to the canal: Socialist Siberia . The Siberians also were alarmed at the consolidation of the South American bloc and its potential to dominate the world economy. They therefore agreed to conduct joint naval exercises in the central Pacific not far from Central America. It was a most peculiar fleet that gathered: Southern Crosses alongside Hammers and Sickles - both sides of World War III, coming together to show their strength. The Siberians and the Oz-Kiwis gambled that South America would not risk war with both powers.

Toward Peace[]

Ecuadorian Admiral José Noritz, the first High Commissioner of the Canal Zone (2007-2013)

The gamble paid off. The ANZ-Siberian fleet avoided open conflict. With the Panama Canal now subject to the control of all of South America, not just Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, cooler heads prevailed to avoid further escalation. All three sides met at Lima in late 2005 to finally re-negotiate the 1977 treaty that was causing so much trouble. In the new treaty, the ANZC recognized South America as the legitimate successor to the Panamanian government insofar as the Canal Zone was concerned. In return, South America dropped the ban against ANZ ships and agreed in principle never to exclude the Commonwealth or Siberia from using the canal for commercial purposes. The treaty was only temporary, with a term of only 5 years. But it successfully prevented a disastrous war.

Relations between the blocs improved after that. ANZC voters, tired of imperialistic grandstanding, sent enough Greens to the ANZ parliament in 2006 that they became part of the governing coalition for the first time. The same year saw the election of Juan Manuel Santos to the Colombian Presidency. Santos had been educated in US and Britain, which helped him be more receptive to Australia-New Zealand's friendly overtures. ANZ military policy shifted from competition with South America to cooperation. Australia-New Zealand forces joined with the newly united South American armed forces to establish new regimes in North America (the Municipal States of the Pacific) and South Africa (the RZA). And talk was beginning on a new forum for international diplomacy: the League of Nations.

When the LoN was founded in September 2008, relations between Oceania and South America were at a high point despite growing economic competition. Within weeks of the LoN's founding, they began to renegotiate the 2005 treaty. This time, a new power bloc had emerged in the Atlantic in the form of the Atlantic Defense Community, an alliance of states in Europe and North Afrrica, together with Canada. The ADC states joined with Siberia and Australia-New Zealand in pressuring South America to adopt a more expansive policy toward other countries' rights in the canal. Accordingly, the 2008 treaty states that the SAC may not discriminate against the ships of any nation passing through the Canal Zone, except in case of war. SAC nations and France are also allowed to keep their privileged status, since their treaty rights predate the 2005 settlement. In addition, the League of Nations was allowed to station a "supervisory" commission in the CZ. It has no actual power in the Zone's governance, but was put in place to monitor the CZ and make sure the treaty terms are carried out. Unlike the 2005 agreement, the Treaty of 2008 has a term of fifty years.

2008 was also the year the South American countries opened their borders. As part of that settlement, the five-nation commission officially took control of the Canal Zone's government. Besides the three permanent members, Brazil and Peru received seats, which were to rotate in 2013 and every five years after that. In the League of Nations, a few motions were made to transfer the CZ to direct LoN administration during 2008 and 2009; none of these advanced because they lacked support in the South American bloc.

The new administration also raised questions of representative government within the CZ. The only part of the Zone to enjoy democracy in 2008 was the Pearl Islands, which had been a fully self-governing community before being annexed in 2003. The mainland portion was administered directly by the SAC authorities, or by those militia groups still running their fiefs on the borders. A newly invigorated SAC military expelled several militias, or threatened or bribed them into leaving, over the course of 2009. By 2010 most of the CZ was under direct South American control. However, outside a few neighborhoods in the rebuilt Panama City, the inhabitants had no real say in their government.

As the citizens and leaders of the post-nuclear world did their best to build civilization and peace from the ashes of Doomsday, the Panama Canal has been at the center of their endeavors. With most of former Panama still in the hands of guerrillas and small groups of survivors, its story is far from finished.

See also[]

- Map of the Canal Zone under US administration

- Panama's population density (1980)

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Gathering Order

- USS Benjamin Franklin

| ||||||||||