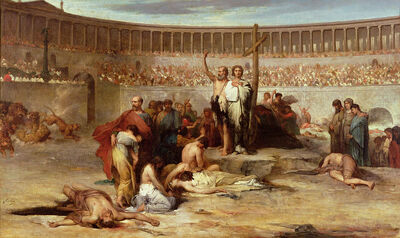

19th Century depiction of the crucifixion of Quintillus in the Flavian Amphitheater.

The Crucifixion of Quintillus in 271 was the most public and violent account of regicide during the crisis of the 3rd century. Following the Battle of the Caelian Hill, Rome erupted into a riot over coinage reforms. This tipping point led to a precipitious downfall of order in the capital city, and the riot became a full-blown revolt. Quintillus, still shamed by the Battle of the Caelian Hill, insisted on leading Rome's forces against the revolt. Instead, disloyal elements in the army and a senatorial scheme led to near anarchy. Quintillus was wounded during the fighting and dragged into the Roman Coliseum where he was publically crucified before his own population. Rome had lost Augusti to humiliating means, but for the Emperor's own citizenry kill him in a frenzy was a signal that the unified Imperial regime over the Mediterranean was in the throes of death.

Background[]

Though the lives of citizens are rarely affected by the passing of one emperor to the next, the capital city was in a state of turmoil and had been for nearly a decade. The Plague of Cyprian at its height killed thousands of Romans per day while famines and draughts in Italy due to the disruption of grain supply out of Egypt killed many more. As farmers abandoned their farms and relocated to urban areas, an influx of desperate people from the outside intermingled with a desperate population already in the city. Rome was a hotbed of violence, teetering on the brink of total eruption.

The months following the succession of Quintillus saw a popular candidate in the military rise against the new Emperor and almost successfully seizing the throne. Despite the usurper's death, confidence in Quintillus remained shaky. Though he was known as a competent administrator, he was not known for his military exploits. During this particularly turbulent period, martial prowess was critical. Quintillus had a number of chances to prove his talent during the Juthungi invasion of Italia. Instead, he was soundly defeated on two occasions before holding the line against the Germanic invaders during the Battle of the Caelian Hill. Though the Juthungi were soundly defeated, the fact remained that Quintillus had all but allowed them to reach the capital city.

To quell an otherwise upset populace, Quintillus spent time in Rome and gather support. He also began enacting a number of coinage reforms to combat the rampant inflation crippling Rome's economy. During this process, he discovered evidence of a conspiracy in the Roman Mint. The chief of coin and a number of other wealthy Romans were discovered to have been tampering with coins and adulterating the amount of silver in each coin. This scheme was making them rich men while the rest of the Empire suffered. Quintillus decided to act and arrest the chief of coin. Upon apprehending him, the workers whipped into a frenzy while the senators profiting from this plot began goading other disloyal elements into a revolt.

Quintillus would not take this sitting down. He sent his armies and a sizable militia to secure the city, with himself fighting in the streets of Rome. His humiliation at allowing the Juthungi to reach Rome, he reasoned, would be outshone by bringing the capital of his empire back from anarchy. This days-long skirmish led to Quintillus being wounded in the fighting and captured. Though it is believed that disloyal senators took advantage of a demoralized army, Quintillus was stabbed in the leg by rioters. That he was escorted to the Coliseum rather than torn apart in the streets suggests that the army played some role in this.

Chronology of Events[]

The wounded Quintillus was dragged from the Caelian Hill by an armed group of revolters. It is likely that these were disloyal soldiers in his army or militia, given that they were able to navigate the mass chaos to the Coliseum. That this event took place at all implies some prior preparation. Whether this was a plot orchestrated by the senate or the military is unknown. In one telling of the narrative, the group carrying the emperor tore off his military garb and clothes, hoisting them on spears and sticks to parade around the streets, chanting about the capture of the Emperor. Other narratives state that the group made their way to the coliseum as quickly and quietly as they could to avoid Quintillus being recaptured by his forces.

The captured Emperor was taken to the Coliseum, where he was quickly and unceremoniously nailed to a cross. According to the most popular and dramatic narratives of the event, the angry mob descended upon the Coliseum. In short time, the entire arena and the seats around it were flooded with people come to see the dying Emperor. The massive crowd gathered at the Coliseum created such a cacophony that they could be heard across Rome. Fighting across the city died down as some people went to the Coliseum to see for themselves while others, hearing the cheers of the masses, knew something had happened and chose to remain inside.

Quintillus' men attempted to seize the Coliseum and drive the crowds out. However, when they heard of the death of their Emperor, the army largely stood down. The riots continued for days around Rome as order continued to break down. At some point, Quintillus' body was stolen and never recovered. When the fighting simmered down enough for the senate to choose another Emperor, the Coliseum was in a complete state of disrepair, with many surfaces heavily vandalized and parts of the arena floor caved in from where it could no longer hold the sheer amount of crowds.