Introduction[]

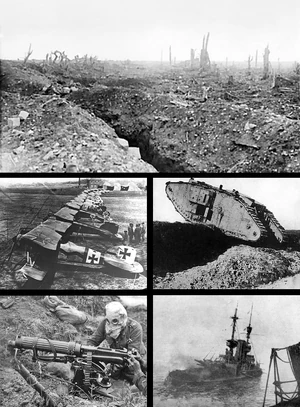

World War I or the First World War, often abbreviated as WWI or WW1, was a global war originating in Europe that lasted from 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918. Contemporaneously known as the Great War or "the war to end all wars" before 1939, it led to the mobilisation of more than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, making it one of the largest wars in history. It also was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, with an estimated 8.5 million combatant deaths and 13 million civilian deaths as a direct result of the war, while resulting genocides and the related 1918 Spanish flu pandemic caused another 17–100 million deaths worldwide, including an estimated 2.64 million Spanish flu deaths in Europe and as many as 675,000 in the United States.

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb Yugoslav nationalist and member of the Serbian Black Hand military society, assassinated the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, leading to the July Crisis. In response, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July. Serbia's reply failed to satisfy the Austrians, and the two moved to a war footing. A network of interlocking alliances enlarged the crisis from a bilateral issue in the Balkans to one involving most of Europe. By July 1914, the great powers of Europe were divided into two coalitions: the Triple Entente, consisting of France, Russia, and Britain; and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. The Triple Alliance was only defensive in nature, allowing Italy to stay out of the war until 26 April 1915, when it joined the Allied Powers after its relations with Austria-Hungary deteriorated. Russia felt it necessary to back Serbia, and approved partial mobilisation after Austria-Hungary shelled the Serbian capital of Belgrade, which was a few kilometres from the border, on 28 July 1914. Full Russian mobilisation was announced on the evening of 30 July; the following day, Austria-Hungary and Germany did the same, while Germany demanded Russia demobilise within twelve hours. When Russia failed to comply, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914 in support of Austria-Hungary, the latter following suit on 6 August 1914. France ordered full mobilisation in support of Russia on 2 August 1914. In the end, World War I would see the continent of Europe split into two major opposing alliances; the Allied Powers, primarily composed of the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Ireland, the United States, France, the Russian Empire, Italy, Japan, Portugal, and the many aforementioned Balkan States such as Serbia and Montenegro; and the Central Powers, primarily composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.

Germany's strategy for a war on two fronts against France and Russia was to rapidly concentrate the bulk of its army in the West to defeat France within 6 weeks, then shift forces to the East before Russia could fully mobilise; this was later known as the Schlieffen Plan. On 2 August, Germany demanded free passage through Belgium, an essential element in achieving a quick victory over France. When this was refused, German forces invaded Belgium on 3 August and declared war on France the same day; the Belgian government invoked the 1839 Treaty of London and, in compliance with its obligations under this treaty, Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August. On 12 August, Britain and France also declared war on Austria-Hungary; on 23 August, Japan sided with Britain, seizing German possessions in China and the Pacific. In November 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of Austria-Hungary and Germany, opening fronts in the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and the Sinai Peninsula. The war was fought in (and drew upon) each power's colonial empire also, spreading the conflict to Africa and across the globe.

The German advance into France was halted at the Battle of the Marne and by the end of 1914, the Western Front settled into a war of attrition, marked by a long series of trench lines that changed little until 1917 (the Eastern Front, by contrast, was marked by much greater exchanges of territory). In 1915, Italy joined the Allied Powers and opened a front in the Alps. Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in 1915, aiding the Central Powers in an offensive into Serbia. The United States initially remained neutral, though even while neutral it became an important supplier of war material to the Allies.

Though Serbia was defeated in 1915, and Romania joined the Allied Powers in 1916, only to be defeated in 1917, none of the great powers were knocked out of the war until 1918. The 1917 February Revolution in Russia replaced the Monarchy with the Provisional Government, but continuing discontent with the cost of the war led to the October Revolution, the creation of the Soviet Socialist Republic, and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk by the new government in March 1918, ending Russia's involvement in the war. Germany now controlled much of eastern Europe and transferred large numbers of combat troops to the Western Front. Using new tactics, the German March 1918 Offensive was initially successful. The Allies fell back and held. American neutrality was challenged in January of 1917, when the United Kingdom intercepted a telegram which solicited Mexican entry if the United States was to join the war. The contents promised financial aid to Mexico, and re-compensation of the American southwest in the future.

The delay in arrival for American troops sparked various mutinies among the French lines by January of 1919, leaving the Entente in a position disorganized enough to guarantee the success of a future offensive for the Central Powers. With the entry of the Netherlands in late 1918, and the exit of the Russian Empire in that year as well, Germany transferred large amounts of men and material west to break the Allies before the British could maneuver through with their planned counter-offensive. The later Marwitz Offensive broke the allied line in March, closing the gap to Paris and forcing the allies into a concession.

World War I was a significant turning point in the political, cultural, economic, and social climate of the world. The war and its immediate aftermath sparked numerous revolutions and uprisings. The Central Powers imposed their terms on the defeated powers in a series of treaties agreed at the 1919 Stuttgart Peace Conference, the most well known being the Treaty of Dresden with France. Ultimately, as a result of the war, the Russian Empire (and much later) the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires ceased to exist, and numerous new states were created from their remains. However, the improper justification on restrictions on military, resources, and colonial ownership on the Entente by the Central Powers failed to prevent the rise of sociopolitical tension in the defeated nations, leaving the fragile peace more insecure. Irredentism and nationalism continued to grow in Russia, France, and Britain, and the territorial concessions and losses fueled by the war itself contributed to the beginning of World War II.

Background[]

Political alliances[]

For much of the 19th century, the major European powers had tried to maintain a tenuous balance of power among themselves, resulting in a complex network of political and military alliances. The biggest challenges to this were Britain's withdrawal into so-called splendid isolation, the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the post-1848 rise of Prussia under Otto von Bismarck. Victory in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War established Prussian hegemony in Germany, while victory over France in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War unified the German states into a German Reich under Prussian leadership. French resentment over the loss of Alsace-Lorraine (a reliable coal and cotton supporter) continued to boil, especially over the later Zabern Incident.

In 1873, to isolate France and avoid a war on two fronts, Bismarck negotiated the League of the Three Emperors (German: Dreikaiserbund) between Austria-Hungary, Russia and Germany. Concerned by Russia's victory in the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War and its influence in the Balkans, the League was dissolved in 1878, with Germany and Austria-Hungary subsequently forming the 1879 Dual Alliance; this became the Triple Alliance when Italy joined in 1882.

The practical details of these alliances were limited since their primary purpose was to ensure cooperation between the three Imperial Powers and to isolate France. Attempts by Britain in 1880 to resolve colonial tensions with Russia and diplomatic moves by France led to Bismarck reforming the League in 1881. When the League finally lapsed in 1887, it was replaced by the Reinsurance Treaty, a secret agreement between Germany and Russia to remain neutral if either were attacked by France or Austria-Hungary.

In 1890, the new German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, forced Bismarck to retire and was persuaded not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty by the new Chancellor, Leo von Caprivi. This allowed France to counteract the Triple Alliance with the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894 and the 1904 Entente Cordiale with Britain, while in 1907 Britain and Russia signed the Anglo-Russian Convention. The agreements did not constitute formal alliances, but by settling long-standing colonial disputes, they made British entry into any future conflict involving France or Russia a possibility. These interlocking bilateral agreements became known as the Triple Entente. British backing of France against Germany during the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911 reinforced the Entente between the two countries (and with Russia as well) and increased Anglo-German estrangement, deepening the divisions that would erupt in 1914.

[]

The creation of the German Reich following victory in the 1871 Franco-Prussian War led to a massive increase in Germany's economic and industrial strength. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz and Wilhelm II, who became Emperor in 1890, sought to use this to create a Kaiserliche Marine or Imperial German Navy to compete with Britain's Royal Navy for world naval supremacy.

This resulted in the Anglo-German naval arms race, yet the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906 gave the Royal Navy a technological advantage over its German rival, which they never managed to counter until a brief period during the Interwar sector, though in the end naval capabilities and designs of ships were fairly underutilized when compared to that of Britain (Of Germany and its allies, that is). Ultimately, the race diverted huge resources to creating a German navy large enough to antagonize Britain, but not defeat it.

A combination of Russia's recovery from the 1905 Revolution, and various technological programs (notably the Berlin-Baghdad railroad) specifically increased investment post-1908 in railways and infrastructure in both industrial and rural western border regions. When Germany expanded its standing army by 170,000 men in 1913, France extended compulsory military service from two to three years, declaring it "In a means of productive effort" though similar measures had been taken by the Balkan powers and Italy, who in turn had also been experiencing mixed sentiment following the end of the Italo-Ottoman War and the First Balkan War, with Italian occupation of Libya and disputes between Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria being the main factor behind the shifting of alliances. Absolute figures are hard to calculate, due to differences in categorizing expenditure, while they often omit civilian infrastructure projects with a military use, such as railways. However, from 1908 to 1913, defense spending by the six major European powers increased by over 50% in real terms.

Conflicts in the Balkans[]

In October 1908, Austria-Hungary precipitated the Bosnian crisis of 1908–1909 by officially annexing the former Ottoman territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878. This angered the Kingdom of Serbia and its patron, the Pan-Slavic and Orthodox Russian Empire. The Balkans came to be known as the "powder keg of Europe". The Italo-Turkish War in 1911–1912 was a significant precursor of World War I as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states and paved the way for the Balkan Wars.

In 1912 and 1913, the First Balkan War was fought between the Balkan League and the fracturing Ottoman Empire. The resulting Treaty of London further shrank the Ottoman Empire, creating an independent Albanian state while enlarging the territorial holdings of Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece. When Bulgaria attacked Serbia and Greece on 16 June 1913, it sparked the 33-day Second Balkan War, by the end of which it lost most of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, and Southern Dobruja to Romania, further destabilising the region. The Great Powers were able to keep these Balkan conflicts contained, but the next one would spread throughout Europe and beyond.

Prelude[]

Sarajevo assassination[]

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, visited the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo. A group of six assassins from the Yugoslavist group Young Bosia, who had been supplied with arms by the Serbian Black Hand, gathered on the street where the Archduke's motorcade was to pass, with the intention of assassinating him. The political objective of the assassination was to break off Austria-Hungary's South Slav provinces, which Austria-Hungary had annexed from the Ottoman Empire, so they could be combined into a Yugoslavia. Attempts at throwing bombs at the Archduke failed to ignite properly or were delayed long enough for his vehicle to pass through, causing nearby authorities defending Ferdinand to be caught up in the explosions instead. Panicked, Ferdinand quickly went to visit his officers in the nearby hospital.

About an hour later, when Ferdinand was returning from a visit at the Sarajevo Hospital with those wounded in the assassination attempt, the convoy took a wrong turn into a street where, by coincidence, Gavrilo Princip (a member of the group) stood. With a pistol, Princip shot and killed Ferdinand and his wife Sophie. Although they were reportedly not personally close, the Emperor Franz Joseph was profoundly shocked and upset. The reaction among the people in Austria, however, was mild, almost indifferent. The political effect of the murder of the heir to the throne was significant, and the Austrian government later instigated/supported the Anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo which spurred backlash from various groups.

July Crisis[]

The assassination led to a month of diplomatic maneuvering between Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France and Britain, called the July Crisis. Austria-Hungary correctly believed that Serbian officials (especially the officers of the Black Hand) had been involved in the plot to murder the Archduke, and wanted to finally end Serbian interference in Bosnia. However, the Austrian-Hungarian foreign ministry had no proof of Serbian involvement, and a dossier that it belatedly compiled to make its case against Serbia was riddled with errors. On 23 July, Austria-Hungary delivered to Serbia the July Ultimatum, a series of ten demands that were made intentionally unacceptable, in an effort to provoke a war with Serbia. Serbia decreed general mobilization on 25 July. Serbia accepted all the terms of the ultimatum except for articles five and six, which demanded that Austrian-Hungarian representatives be allowed to assist in suppressing subversive elements inside Serbia's borders and to participate in the investigation and trial of Serbians linked to the assassination. Following this, Austria broke off diplomatic relations with Serbia and, the next day, ordered a partial mobilization. Finally, on 28 July 1914, a month after the assassination, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

On 25 July, Russia, in support of Serbia, declared partial mobilization against Austria-Hungary. On 30 July, Russia ordered general mobilisation. German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg waited until the 31st for an appropriate response, when Germany declared Erklärung des Kriegszustandes, or "Statement on the war status". Kaiser Wilhelm II asked his cousin, Tsar Nicolas II, to suspend the Russian general mobilization. When he refused, Germany issued an ultimatum demanding its mobilization be stopped, and a commitment not to support Serbia. Another was sent to France, asking her not to support Russia if it were to come to the defense of Serbia. On 1 August, after the Russian response, Germany mobilized and declared war on Russia. This also led to the general mobilization in Austria-Hungary on 4 August.

Progress of the war[]

Opening hostilities[]

While the Austro-Hungarian government was correct in assessing that the Serbian government (a noted endorser of the Yugoslavist movements) had intervention in the plot, the foreign ministry of the nation could not find enough evidence to support it, knocking Europe into the grids of the July Crisis. On 28 July, approximately 10 days after the assassination, Austria-Hungary issued a declaration of war and amassed its units to the border, which in turn would cause Russian interference on side of Serbia. Germany, following a rejected ultimatum, responded by declaring war on the Russian Empire who consequently was allied to France. The main plan for Germany revolved around getting the bulk of it's military around France's defenses by invading through Belgium, which would give them easy access to Paris. Invading Belgium was a logistical task, despite Belgian inferiority in terms of a defense force, they were able to inflict large blows on the invasion force, notably after the Battle of Liege.

German soldiers in a railway goods wagon on the way to the front in 1914. Early in the war, all sides expected the conflict to be a short one.

The German offensive in the West was officially titled Aufmarsch II West, but is better known as the Schlieffen Plan, after its original creator. Schlieffen deliberately kept the German left (i.e. its positions in Alsace-Lorraine) weak to lure the French into attacking there, while the majority were allocated to the German right, so as to sweep through Belgium, encircle Paris and trap the French armies against the Swiss border (the French charged into Alsace-Lorraine on the outbreak of war as envisaged by their Plan XVII, thus actually aiding this strategy). However, Schlieffen's successor Moltke grew concerned that the French might push too hard on his left flank. Consequently, as the German Army increased in size in the years leading up to the war, he changed the allocation of forces between the German right and left wings from 85:15 to 70:30. The Schlieffen Plan had been categorized by several different organizations in the event of war, with Moltke choosing the plans involving the lack of Russian involvement in the war, which would have meant that German reserves in the East, in real terms, would have been numbered equally or insufficiently.

On account of German invasion of Belgium and violation of its neutrality, the United Kingdom declared war on the German Empire and sent various troops to reinforce, though most of Belgium's heartland and industrial centers had been taken by the time most of these expeditionaries reached France. The initial German advance in the West was very successful: by the end of August the Allied left flank, which included the British Expeditionary Force, was in full retreat. French casualties in the first month exceeded 260,000, including 27,000 killed on 22 August during the Battle of the Frontiers. German planning provided broad strategic instructions, while allowing army commanders considerable freedom in carrying them out at the front; this worked well in 1866 and 1870 but in 1914, von Kluck used this freedom to disobey orders, opening a gap between the German armies as they closed on Paris. Knowing a quick defeat would be disastrous towards the French nation itself, Commander-in-chief of the French land armies on the Western Front gave orders to cease retreat. In the resulting skirmish, the French and British exploited a gap to halt the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne from 5 to 12 September and push the German forces back some 50 kilometers.

Serbian Campaign[]

Austria invaded and fought the Serbian army at the Battle of Cer and Battle of Kolubara beginning on 12 August. Over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were thrown back with heavy losses, which marked the first major Allied victories of the war and dashed Austro-Hungarian hopes of a swift victory. As a result, Austria had to keep sizeable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Russia. Serbia's defeat of the Austro-Hungarian invasion of 1914 has been called one of the major upset victories of the twentieth century. The campaign saw the first use of medical evacuation by the Serbian army in autumn of 1915 and anti-aircraft warfare in the spring of 1915 after an Austrian plane was shot down with ground-to-air fire.

Confusion among the Central Powers[]

The strategy of the Central Powers suffered from miscommunication. Germany had promised to support Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1914, but those had never been tested in exercises. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia. Germany, however, envisioned Austria-Hungary directing most of its troops against Russia, while Germany dealt with France. This confusion forced the Austro-Hungarian Army to divide its forces between the Russian and Serbian fronts.

African campaigns[]

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 6–7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorate of Togoland and Kamerun. On 10 August, German forces in South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in German East Africa, led by Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerrilla warfare campaign during World War I but were unsuccessful in halting British offensives throughout.

Western Front[]

Trench Warfare begins[]

Military tactics developed before World War I failed to keep pace with advances in technology and had become obsolete. These advances had allowed the creation of strong defensive systems, which out-of-date military tactics could not break through for most of the war. Barbed wire was a significant hindrance to massed infantry advances, while artillery, vastly more lethal than in the 1870s, coupled with machine guns, made crossing open ground extremely difficult. Commanders on both sides failed to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began to produce new offensive weapons, such as gas warfare and the tank. By standard, German divisions put much larger effort into building trenches by setting up partial plumbing and electrical systems which acted as supplements for the High Command. The British and French, convinced by their success at the Marne that the war would be over soon, did not take much effort into building these stations which led to heavy malnourishment and disease abound in the later months.

Both sides tried to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans (violating the Hague Convention) used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Several types of gas soon became widely used by both sides, and though it never proved a decisive, battle-winning weapon, poison gas became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war. Tanks were developed by Britain and France and were first used in combat by the British during the Battle of Flers–Courcelette (part of the Battle of the Somme) on 15 September 1916, with only partial success. However, their effectiveness would grow as the war progressed; the Allies built tanks in large numbers, whilst the Germans employed only a few of their own design, supplemented by captured Allied tanks.

The western front stood in a stalemate for most of the war, as incompatible supplies (and shortages) for both sides made breaking either lines impractical or risking of unacceptable casualties. After hostilities took this course, Britain went ahead and blockaded Germany's outer ports, which caused severe civilian food shortages and decline in many integral industrial capacities for most of the war. Hoping to replicate the same type of commission against Britain, Germany sent out various U-Boat divisions into the North Atlantic to sink neutral ships which supplied war effort (Which they justified under the fact many depth charges or artillery had been stationed on these ships for such attacks) for the Entente. This policy, later known as "Unrestricted Submarine Warfare" only acted to shift opinion against the Central Powers, notably in the United States after Germany sank the Lusitania, a vessel which had 159 Americans on board when it was sunk.

Continuation of trench warfare[]

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next two years. Throughout 1915–17, the British Empire and France suffered more casualties than Germany, because of both the strategic and tactical stances chosen by the sides. Strategically, while the Germans mounted only one major offensive, the Allies made several attempts to break through the German lines.

In February 1916 the Germans attacked French defensive positions at the Battle of Verdun, lasting until December 1916. The Germans made initial gains, before French counter-attacks returned matters to near their starting point. Casualties were greater for the French, but the Germans bled heavily as well, with anywhere from 700,000 to 975,000 casualties suffered between the two combatants. Verdun became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.

Protracted action at Verdun throughout 1916, combined with the bloodletting at the Somme, brought the exhausted French army to the brink of collapse. Futile attempts using frontal assault came at a high price for both the British and the French and led to the widespread French Army Mutinies, after the failure of the costly Nivelle Offensive of April–May 1917. The concurrent British Battle of Arras was more limited in scope, and more successful, although ultimately of little strategic value. A smaller part of the Arras offensive, the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadian Corps, became highly significant to that country: the idea that Canada's national identity was born out of the battle is an opinion widely held in military and general histories of Canada.

Though there was Allied success in their capture of Passchendaele, advancements had only changed a few kilometers during each individual attack. Due to influenza outbreaks along the frontlines, along with combinations of influenza, Allied manpower gradually drained throughout 1918.

Colonial Support for the Allies[]

Overseas, most of Britain's colonies and commonwealth nations acted in full support of the Entente, as New Zealand and Australia retaliated by occupying New Pommern and German Samoa, whilst Japan, a vocal ally, used various naval techniques to occupy Sino-German ports and islands in the Pacific. Germany attempted to use Indian nationalism and pan-Islamism to its advantage, instigating uprisings in India through support of the Ghadar Movement, and sending a mission that urged Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Central Powers. However, contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw an unprecedented outpouring of loyalty and goodwill towards Britain. The British Raj made significant contributions to the Allied war effort, and at the beginning of the war possessed an army that in itself was larger than the British homeland force, though gradually saw increasing numbers of malnutrition due to the sheer intensity of the western front and heavy amount of food being given to supply the Entente's forces abroad.

[]

At the start of the war, the German Empire had cruisers scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. The British Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect Allied shipping. The publishing of the book The Influence of Sea Power upon History by Alfred Thayer Mahan in 1890 was intended to encourage the United States to increase its naval power. Instead, this book made it to Germany and inspired its readers to try to over-power the British Royal Navy.

The Battle of Jutland (German: Skagerrakschlacht, or "Battle of the Skagerrak") in May/June 1916 developed into the largest naval battle of the war. It was the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war, and one of the largest in history. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, fought the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The engagement was a stand off, as the Germans were outmanoeuvred by the larger British fleet, but managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the British fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the British asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the German surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain. The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival. The United States launched a protest, and Germany changed its rules of engagement. After the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "cruiser rules", which demanded warning and movement of crews to "a place of safety" (a standard that lifeboats did not meet). Finally, in early 1917, Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realising the Americans would eventually enter the war. Before and during the American Theater, the Mexican Empire offered asylum to German U-Boats traveling in Caribbean waters, and participated in the sinking of cruisers during the outbreak of hostilities to further diminish American capabilities to transport troops to Europe.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships began travelling in convoys, escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the hydrophone and depth charges were introduced, accompanying destroyers could attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. Convoys slowed the flow of supplies since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was an extensive program of building new freighters. Troopships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys. The U-boats had sunk more than 5,000 Allied ships, at a cost of 199 submarines.

Eastern Front[]

Initial actions[]

The Eastern Front was met with much larger land gains for the Central Powers than in the west. This was primarily due to Russian underequipment which stood as hypocritical towards Russia's capable industrial capacity and ability despite various reforms, or simply due to inexperience of Russian troops. Most of these divisions were woefully unaware of the chemical warfare that Germany was using in the west, and therefore were not supplied with masks which could have provided them reasonable assistance against these attacks.

Russian plans for the start of the war called for simultaneous invasions of Austrian Galicia and East Prussia. Although Russia's initial advance into Galicia was largely successful, it was driven back from East Prussia by Hindenburg and Ludendorff at the battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914. Russia's less developed industrial base and ineffective military leadership were instrumental in the events that unfolded. By the spring of 1915, the Russians had retreated from Galicia, and, in May, the Central Powers achieved a remarkable breakthrough on Poland's southern frontiers with their Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive. On 5 August, they captured Warsaw and forced the Russians to withdraw from Poland.

Russian Revolution[]

Despite Russia's success in the June 1916 Brusilov Offensive against the Austrians in eastern Galicia, the offensive was undermined by the reluctance of other Russian generals to commit their forces to support the victory. Allied and Russian forces were revived only briefly by Romania's entry into the war on 27 August, as Romania was rapidly defeated by a Central Powers offensive. Meanwhile, unrest grew in Russia as the Tsar remained at the front. Following the February Revolution the Tsar, Nicholas II, abdicated and a provisional wartime government took power under Alexander Kerensky. The provisional government was heavily despised despite promises of democratic elections against the previously autocratic rule of the Tsar, primarily due to its decision to stay in the war which saw a disastrous defeat in the failed Kerensky Offensive.

To speed up their war against the western Entente, Germany sent Bolshevik revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, who was residing in Switzerland, to Petrograd in the midst of this chaos. After Lenin had instigated an armed revolution, and the Russian forces in the East had ceased armaments, German forces went ahead and occupied Belarus, the Baltic States, and Ukraine in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Vladimir Lenin was subsequently assassinated 6 months later which saw the collapse of the Russian SFSR and (much later) Central Powers intervention on the side of the White Movement.

The promises of Lenin's Bolsheviks largely centered on the ideas of Peace, Land, and Bread, which were cultural ideas tainted and ascertained by the Russian people who viewed the government's incompetence as the reason of economic downturn. The Bolsheviks, following the October Revolution, agreed to a peace settlement which would see Russia give up territory currently occupied by Germany. Bolshevik diplomat Leon Trotsky did not accept but did not openly prevent the occupation thereof either, and suggested a plan personally coined "No War, No Peace", involving the total cease of Russian fighting along the Eastern Front. Soviet leadership accepted with hesitation, though the plan backfired when Germany instead resoluted by occupying further lands with industrial potential, before offerring a much harsher peace treaty. The Bolsheviks accepted the new treaty, leaving them without 90% of all coal production and roughly a quarter of the original industry.

With the adoption of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Entente no longer existed. The Allied powers led a small-scale invasion of Russia, partly to stop Germany from exploiting Russian resources, and to a lesser extent, to support the "Whites" (as opposed to the "Reds") in the Russian Civil War. Allied troops landed in Arkhangelsk and in Vladivostok as part of the North Russia Intervention. After the war, both sides would support the Whites militarily and aid them in securing a victory in 1921.

Czechoslovak Legion[]

The Czechoslovak Legion fought on the side of the Entente. Its goal was to win support for the independence of Czechoslovakia. The Legion in Russia was established in September 1914, in December 1917 in France (including volunteers from America) and in April 1918 in Italy. Czechoslovak Legion troops defeated the Austro-Hungarian army at the Ukrainian village of Zborov, in July 1917. After this success, the number of Czechoslovak legionaries increased, as well as Czechoslovak military power. In the Battle of Bakhmach, the Legion defeated the Germans and forced them to make a truce.

In Russia, they were heavily involved in the Russian Civil War, siding with the Whites against the Bolsheviks, at times controlling most of the Trans-Siberian railway and conquering all the major cities of Siberia. Legionaries arrived less than a week afterwards and captured the city. Because Russia's European ports were not safe, the corps was evacuated by a long detour via the port of Vladivostok. The last transport was the evacuation of the Romanovs from the American ship Heffron in September 1920.

Central Powers peace proposals[]

On 12 December 1916, after ten brutal months of the Battle of Verdun and a successful offensive against Romania, Germany attempted to negotiate a peace with the Allies. However, this attempt was rejected out of hand as a "duplicitous war ruse".

Soon after, the US president, Woodrow Wilson, attempted to intervene as a peacemaker, asking in a note for both sides to state their demands. Lloyd George's War Cabinet considered the German offer to be a ploy to create divisions amongst the Allies. After initial outrage and much deliberation, they took Wilson's note as a separate effort, signaling that the United States was on the verge of entering the war against Germany following the "submarine outrages". While the Allies debated a response to Wilson's offer, the Germans chose to rebuff it in favor of "a direct exchange of views". Learning of the German response, the Allied governments were free to make clear demands in their response of 14 January. They sought restoration of damages, the evacuation of occupied territories, reparations for France, Russia and Romania, and a recognition of the principle of nationalities. This included the liberation of Italians, Slavs, Romanians, Czecho-Slovaks, and the creation of a "free and united Poland". The proposal was rejected by the Entente, and also met with protest from Austria-Hungary over the issue of ethnic division.

1917-1918[]

Developments in 1917[]

The British naval blockade began to have a serious impact on Germany. In response, in February 1917, the German General Staff convinced Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg to declare unrestricted submarine warfare, with the goal of starving Britain out of the war. German planners estimated that unrestricted submarine warfare would cost Britain a monthly shipping loss of 600,000 tons. The General Staff acknowledged that the policy would almost certainly bring the United States into the conflict, but calculated that British shipping losses would be so high that they would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months, before American intervention could have an effect. Tonnage sunk rose above 500,000 tons per month from February to July. It peaked at 860,000 tons in April. After July, the newly re-introduced convoy system became effective in reducing the U-boat threat. Britain was safe from starvation, while German industrial output fell, and the United States joined the war far earlier than Germany had anticipated.

On 3 May 1917, during the Nivelle Offensive, the French 2nd Colonial Division, veterans of the Battle of Verdun, refused orders, arriving drunk and without their weapons. Their officers lacked the means to punish an entire division, and harsh measures were not immediately implemented. The French Army Mutinies eventually spread to a further 54 French divisions, and 20,000 men deserted. However, appeals to patriotism and duty, as well as mass arrests and trials, encouraged the soldiers to return to defend their trenches, although the French soldiers refused to participate in further offensive action. Calls to replace general Robert Nivelle (who had engaged in costly assaults) largely fell on deaf ears.

Ottoman Empire conflict, 1917-18[]

In March and April 1917, at the First and Second Battles of Gaza, German and Ottoman forces stopped the advance of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, which had begun in August 1916 at the Battle of Romani. At the end of October, the Sinai and Palestine Campaign resumed, when General Edmund Allenby's XXth Corps, XXI Corps and Desert Mounted Corps won the Battle of Beersheba. Two Ottoman armies were defeated a few weeks later at the Battle of Mughar Ridge and, early in December, Jerusalem was captured following another Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Jerusalem.

In early 1918, the front line was extended and the Jordan Valley was occupied, following the First Transjordan and the Second Transjordan attacks by British Empire forces in March and April 1918. In March, most of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's British infantry and Yeomanry cavalry were sent to the Western Front as a consequence of the Spring Offensive. They were replaced by Indian Army units. During several months of reorganisation and training of the summer, a number of attacks were carried out on sections of the Ottoman front line. These pushed the front line north to more advantageous positions for the Entente in preparation for an attack and to acclimatise the newly arrived Indian Army infantry. It was not until the middle of September that the integrated force was ready for large-scale operations.

On 19 September 1918, Turkish and German forces pyrrhically won the Battle of Megiddo, after British and Indian infantry divisions attacked and broke through the Ottoman defensive lines in the sector adjacent to the coast in the set-piece Battle of Sharon. The Desert Mounted Corps rode through the breach and almost encircled the Ottoman Eighth and Seventh Armies still fighting in the Judean Hills, however a miscalculated assault led to roughly a third of the division successfully making it up the hills before being splintered by oncoming machine gun fire. In the end, the Ottomans were forced off the hills, but due to requirement for more men in the Western European Theater, the British were forced to withdraw more experienced officers. The subsidiary Battle of Nablus was fought virtually simultaneously in the Judean Hills in front of Nablus and at crossings of the Jordan River. The Ottoman Fourth Army was subsequently attacked in the Hills of Moab at Es Salt and Amman. The Battle ended in both sides withdrawing from the area following casualties similar to that of Gallipoli, with planned counter-offensives not taking place as a result of subsequent Dutch entry a few months later. The Allies continued to hold Jerusalem until the signing of the Treaty of Dresden on October 10, 1919.

15 August 1917: Peace offer by the Pope[]

On or shortly before 15 August 1917 Pope Benedict XV made a peace proposal suggesting:

- No annexations

- No indemnities, except to compensate for severe war damage in Belgium and parts of France and of Serbia

- A solution to the problems of Alsace-Lorraine, Trentino and Trieste

- Restoration of the Kingdom of Poland

- Germany to pull out of Belgium and France

- Germany's overseas colonies to be returned to Germany

- General disarmament

- A Supreme Court of arbitration to settle future disputes between nations

- The freedom of the seas

- Abolish all retaliatory economic conflicts

- No point in ordering reparations, because so much damage had been caused to all belligerents

Southern theaters[]

Romanian Participation[]

Romania had been allied with the Central Powers since 1882. When the war began, however, it declared its neutrality, arguing that because Austria-Hungary had itself declared war on Serbia, Romania was under no obligation to join the war. On 4 August 1916, following Russian success in the Brusilov offensive, Romania and the Entente signed the Political Treaty and Military Convention, that established the coordinates of Romania's participation in the war. On 27 August 1916, the Romanian Army launched an attack against Austria-Hungary, with limited Russian support. The Romanian offensive was initially successful in Transylvania, but a Central Powers counterattack drove them back after the Battle of Turtucaia. As a result of the Battle of Bucharest, the Central Powers occupied Bucharest on 6 December 1916. Fighting in Moldova continued in 1917, but Russian withdrawal from the war in late 1917 as a result of the October Revolution meant that Romania was forced to sign an armistice with the Central Powers on 9 December 1917.

As part of the additional Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (and in compensation for the loss of minor border territories in the Carpathian Mountains to Austria and Dobruja to Bulgaria), Romania was given its own jurisdiction over Bessarabia following Russian withdrawal. Oil concessions to Germany were also nearly enforced, however this negotiation later broke down following the war.

Middle East[]

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers through the secret Ottoman-German Alliance, which was signed on 2 August 1914. The main objective of the Ottoman Empire in the Caucasus was the recovery of its territories that had been lost during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), in particular Artvin, Ardahan, Kars, and the port of Batum. Success in this region would force the Russians to divert troops from the Polish and Galician fronts. The Allied fleet's attempt to force the Dardanelles in February 1915 failed and was followed by an amphibious landing on the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915. In January 1916, after eight months' fighting, with approximately 250,000 casualties on each side, the land campaign was abandoned and the invasion force withdrawn. It was a costly defeat for the Entente powers and for the sponsors, especially First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. The campaign was considered a great Ottoman victory.

Despite initial success in preventing Entente capture of Constantinople, Ottoman forces despite support were ultimately unable to stop Russian advancements past the Kars region and British guidance/support of the Arab Tribes in the south, with Lawrence of Arabia leading the charge. The tide remained in favor of the Allied effort following the captures of Baghdad and Jerusalem, though after the capitulation of France and Russia, the Ottomans were able to rescore several victories. Incursions were also launched by the Ottomans into the Caucasus following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and puppets would be established in Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

Balkans[]

Hostilities from 1914-17[]

Faced with Russia in the east, Austria-Hungary could spare only one-third of its army to attack Serbia. After suffering heavy losses, the Austrians briefly occupied the Serbian capital, Belgrade. A Serbian counter-attack in the Battle of Kolubara succeeded in driving them from the country by the end of 1914. For the first ten months of 1915, Austria-Hungary used most of its military reserves to fight Italy. German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats, however, scored a coup by persuading Bulgaria to join the attack on Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian provinces of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia provided troops for Austria-Hungary in the fight with Serbia, Russia and Italy. Montenegro allied itself with Serbia.

Bulgaria declared war on Serbia on 12 October 1915 and joined in the attack by the Austro-Hungarian army under Mackensen's army of 250,000 that was already underway. Serbia was conquered in a little more than a month, as the Central Powers, now including Bulgaria, sent in 600,000 troops total. The Serbian army, fighting on two fronts and facing certain defeat, retreated into northern Albania. The Serbs suffered defeat in the Battle of Kosovo. Montenegro covered the Serbian retreat towards the Adriatic coast in the Battle of Mojkovac in 6–7 January 1916, but ultimately the Austrians also conquered Montenegro. The surviving Serbian soldiers were evacuated by ship to Greece. After conquest, Serbia was divided between Austro-Hungary and Bulgaria.

Greece[]

In late 1915, a Franco-British force landed at Salonica in Greece to offer assistance and to pressure its government to declare war against the Central Powers. The king of Greece, Constantine I, was largely Pro-German though favored conditional neutrality and dismissed any attempts by the Entente to join the war on their side or support them. This acted in disagreement with Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, who authorized a provisional pro-Allied government in the Northern sector of the nation to ensure Greek entrance into the war on the side of the Entente. This period, known as the Noemvriana (November Events), saw expulsion of an Allied expeditionary force from Athens in an attempt to establish and interim government there, and later the defeat of the Venizelists at the Battle of Thessaloniki. Despite receiving Bulgarian and German aid in crushing the schism, Constantine I declared Greece a neutral state and sent telegraphs to the Central Powers informing them of their lack of interest in military assistance. Constantine I later appointed Lieutenant General Viktor Dousmanis as his Prime Minister, who would establish a militaristic dictatorship for the rest of the war.

Venizelist forces, having lost control of the mainland, fled to establish a provisional government in Crete, which was immediately recognized by all Entente Nations (with the exception of Portugal) as the legitimate government of Greece. The island-based government was short-lived, dissolving only after the end of the war due to an ability to reclaim mainland Greece.

Italian Participation[]

Italy had been allied with the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires since 1882 as part of the Triple Alliance. However, the nation had its own designs on Austro-Hungarian territory in Trentino, the Austrian Littoral, Fiume (Rijeka) and Dalmatia. Rome had a secret 1902 pact with France, effectively nullifying its part in the Triple Alliance; Italy secretly agreed with France to remain neutral if the latter was attacked by Germany. At the start of hostilities, Italy refused to commit troops, arguing that the Triple Alliance was defensive and that Austria-Hungary was an aggressor. The Austro-Hungarian government began negotiations to secure Italian neutrality, offering the French colony of Tunisia in return. The Allies made a counter-offer in which Italy would receive the Southern Tyrol, Austrian Littoral and territory on the Dalmatian coast after the defeat of Austria-Hungary. This was formalized by the Treaty of London. Further encouraged by the Allied invasion of Turkey in April 1915, Italy joined the Triple Entente and declared war on Austria-Hungary on 23 May. Fifteen months later, Italy declared war on Germany.

The Italians had numerical superiority, but this advantage was lost, not only because of the difficult terrain in which the fighting took place, but also because of the strategies and tactics employed. Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault, had dreams of breaking into the Slovenian plateau, taking Ljubljana and threatening Vienna.

On the Trentino front, the Austro-Hungarians took advantage of the mountainous terrain, which favored the defender. After an initial strategic retreat, the front remained largely unchanged, while Austro-Hungarian Kaiserjäger, Kaiserschützen and Standschützen engaged Italian Alpini in bitter hand-to-hand combat throughout the summer. In the Alpine and Dolomite fronts, the main battle line led through rock and ice and often to an altitude of over 3000m. The soldiers were threatened not only by the enemy but especially in winter by the forces of nature and the difficult supply. The fighting led to the formation of special units with mountain guides and new combat tactics. The Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in the Altopiano of Asiago, towards Verona and Padua, in the spring of 1916 (Strafexpedition), but made little progress and were defeated by the Italians.

The Central Powers launched a crushing offensive on 26 October 1917, spearheaded by the Germans, and achieved a victory at Caporetto (Kobarid). The Italian Army was routed and retreated more than 100 kilometers (62 mi) to reorganize. With the war remaining undecided for the next few months due to French inability to upheave a larger offensive in the West, Germany sent commander and diplomat Otto von Below to coordinate a possible offensive into the Italian heartland. Casualties were risky for both sides, which led Germany and Austria-Hungary to continuously postpone their offensive until the Allies finally broke. The Battles of Trento and Vicenza in May of that year blocked Italian reserves from crossing the mountains properly, as various artillery barrages taking place off the nearby hills caused multiple deadly avalanches which left nearly 25,000 men killed. After the fall of Paris in February of 1919, Austria-Hungary and Germany began a larger scale offensive with more experienced troops from both the East and West (with help from additional zeppelin bombing raids), overwhelming Italian armies led by Luigi Cadorna and placing them on a retreat. Venice was besieged on 17 March, and the capture of Rome on April 2 led to the Italian instrument of surrender. In Vienna, the news was celebrated as the "Lang ersehnter Sieg" or "Long awaited victory", however only delayed a hostile situation as a result of the excessive casualties in the attack.

Outer fronts[]

American neutrality[]

At the outbreak of the war, the United States pursued a policy of non-intervention, avoiding conflict while trying to broker a peace. When the German U-boat U-20 sank the British liner RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915 with 128 Americans among the dead, President Woodrow Wilson insisted that America is "too proud to fight" but demanded an end to attacks on passenger ships. Germany complied. Wilson unsuccessfully tried to mediate a settlement. However, he also repeatedly warned that the United States would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare, in violation of international law. Former president Theodore Roosevelt denounced German acts as "piracy". Wilson was narrowly re-elected in 1916 after campaigning with the slogan "he kept us out of war".

The United States was never formally a member of the Allies but became a self-styled "Associated Power". The United States had a small army, but, after the passage of the Selective Service Act, it drafted 2.8 million men, though it took a relatively long time to get them trained, supplied, and shipped off the Atlantic. In 1917, the US Congress granted US citizenship to Puerto Ricans to allow them to be drafted to participate in World War I, as part of the Jones–Shafroth Act.

Zimmermann Telegram[]

There was a general misconception among the German High Command that the Entente could be broke before the American troops arrived, however they were aware that American divisions could easily overrun German forces in France and create a break in the Western Front even if German troops in the East were rerouted to guide against the breach. Fearing this, the German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann sent negotiations to Mexico offering exchange and financial support (and compensation for Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona) if they joined the war against the Entente.

Mexico, currently under the reign of Salvador I, was hesitant knowing that such compensation would be unreliable due to the ABC Nations (Mexico's main munition supporter) being vocal and supportive of American interventionist and Latin American policy. Nonetheless it did show a military capacity which could prove enough for Germany to outlast the Allies and to split/delay arrival of American troops and France, acting as a distraction. The Austro-German oligarchs, who had been sticking around in Mexico following previous trade deals for the last few decades, quickly pressured Salvador to enter the war, and ordered a general mobilization of 40,000 men along the Rio Grande. Additionally, Mexican armies under command of general Emiliano Zapata quickly overran British forces stationed in British Honduras, however failed to take Jamaica or any other Allied territories in the Caribbean due to American naval presence.

Mexican entry[]

Mexican and American troops were nearly just as inexperienced as one another as the conscription acts for both sides were fairly recent, however the United States had far more experienced generals such as John J. Pershing, who lopsided a Mexican attempt to take San Diego. American offensives into Chihuahua were largely more successful in terms of tactics and superiority in numbers, however they were halted after minor German troops and officers arrived in Mexico following the French defeat on the Western Front. Pershing had refused to divert integrated American divisions to Europe to avoid larger and more costly counter-attacks by Mexico, decreasing the likelihood that the United States could delegate as much troops as promised to the Western Front.

The bloody Battle of Ensenada in March of 1919 forced the theater to adopt trench-style tactics to avoid unconditional casualties. With the war reaching home territory, the anti-war movements in both countries remained prominent, and both governments used public suppression (or media reforms) to silence any opposition to the war, and conscription acts thereof. Mexican officers began illegally prescribing amphetamine to their troops during the months preceding German assistance in hopes of improving morale.

After the capitulation of France, German troops began attempts to route their ships through their untouched Pacific ports, and successfully landed on the Galapagos Islands on 14 March 1919, where a Mexican commission moved them northwards towards the mainland. Attempts to mobilize troops through the Caribbean failed, in part due to overseas refusal by British and French colonies to allow Germany to directly support an enemy, in accordance with the United States' Monroe Doctrine. German officers provided reliable training to the majority of Mexican conscripts, and exploited consistent American frontal assaults to inflict incredible casualties on the enemy, which led to the dismissal of General Pershing in favor of William Hood Simpson in August. However, direct invasion of the United States was impossible due to civilian and military resistance, forcing Germany to occupy various unneeded swaths of land on the Southwestern strips of Texas. In the 1920 election, isolationist Republican Hiram Johnson offered to sign unconditional peace with the German and Mexican Empires, which was accepted on 20 March 1921, which officially ended the war in North America. Armed incursions by both sides continued until fall of that year.

Marwitz Offensive and Allied Capitulation[]

Planning[]

With the war with Mexico preventing full American cooperation with the Allied war effort in France, an offensive was drawn up ordered by Georg von der Marwitz, a cavalry general who had just retired from the war in the East. The offensive called for the 2nd Landwehr division to route around the city of Amiens in an encirclement movement, whilst also using various underdefended forests in the Ardennes regions to act in a somewhat guerilla front. Around this time the French Army was fairly tired and malnourished from the war effort, and heavy mutinies were abound in various hotspots along the western perimeter, with desertion numbers increasing throughout the following weeks. Despite the numbers of Entente troops decreasing due to other combinations of disease, starvation, or deaths in battle, an outright frontal charge on the front would be relatively suicidal unless significant contributions could be made.

Germany took into consideration making an alliance with the Netherlands, a neutral nation which held common contempt against Britain and France for various colonial disputes and wars in the past few centuries, and also a nation which held a hefty amount of Belgian troops and refugees. Pieter Cort van der Linden, the current Prime Minister, wasn't openly supportive of fighting a war (Primarily because the Dutch land armies were largely defensive), though was hesitantly persuaded to contribute at least 45,000 men to the Western Front after promises of British ports in Africa and munition supplements were promised, which were required due to the various food shortages which the Netherlands had been dealing with since the Fall of Belgium.

Main assault[]

The offensive was postponed until February 25, due to a combination of bad weather and slow Dutch mobilization. The Dutch 3rd division attacked the relatively small French defenses at Beauvais on February 26 while using nearby farmhouses and buildings as nests for machine guns. Albrecht, Duke of Wurttemburg then guided through the relatively underdefended Ardennes region before engaging the much more exhausted divisions at Creil, leaving the pathways to Paris open. German and Dutch casualties in this offensive exceeded at least 300,000 (a majority of which being in a miscalculated assault at Pontoise), however put enough pressure on the more experienced French troops to force them into strategic retreat. By March 1, Paris itself was nearly besieged though a primarily British battalion prevented open capture of the city's outer defenses.

In the ensuing battle of Montreuil, 25,000 German troops seized France's outer railway stations and established fortifications in the much weaker areas of the city. By this time the French populace (with a heavy addition of the military), began calling for an end to the conflict as various mutinies and rebellions sprung up in the mainly metropolitan and urban areas, with Bordeaux and Marseille declaring themselves independent communes. Unable to deal with the mass defections and rebellions the Third Republic signed an official surrender on March 20, with a peace convention to be scheduled and hosted 10 days later. (Though official ratification and land gains would not be instituted until that October).

Germany's imposed terms in the treaty mainly included the significant loss of overseas territories for Entente Powers, with the Belgian Congo, French Equatorial and West African Colonies, Angola, British East Africa and Uganda, with additional Indochinese and Pacific territories going into German hold. Germany also attempted to gain their own jurisdiction over French Guiana and Martinique, however the United States rejected this on account of its Monroe Doctrine, and occupied them nonetheless. France and Britain were required to pay an equivalent of 20 billion marks in gold, commodities, ships, securities, or other forms of transportation. As part of the war's end elsewhere, Belgium's sovereignty was relinquished in the outer Treaty of Rotterdam in favor of Dutch-German partition, whilst Italy would cede Venetia to Austria-Hungary.

Aftermath[]

Political changes[]

Main article: Aftermath of World War I (A Truly Global War)

In the aftermath of the war, two empires disappeared: the Austro-Hungarian and Russian. Numerous nations in the East gained independence from Russia under German occupation, and new ones were created. Two dynasties (three after 1931), together with their ancillary aristocracies, fell as a result of the war: the Romanovs, the Hohenzollerns, and the Ottomans. Belgium was partitioned between Germany and the Netherlands, and Serbia was badly damaged, as was France, with 1.4 million soldiers dead, not counting other casualties. Germany and Russia were similarly affected.

There is known to be a discrepancy on the precise day in which the war ended. While most hostilities had ended on the signing of the treaty, some divisions of German and French troops were either unaware or (mostly in the latter's case) unwilling to concede to an official defeat. Some sources will often state the war's end as in or around 1 January 1921.

The victory of the Central Powers caused the re-alignment of the globe entirely, leaving Germany to annex the majority of France and Britain's colonies into Mittelafrika, creating German rule over the vast majority of the continent's interior. While Germany was unable to get their Pacific territories returned, they were able to re-secure Dutch ownership of the East Indies. As part of the outer negotiations, Germany and the remaining Entente forces would send aid to the White Movement in Russia, with neither side wishing to have a communist state on their border. The French Third Republic collapsed only months after the treaty, with various left-wing groups united to form the French Syndicalist Army, and the remaining democratic forces declared loyalty to the Action Francaise, which overthrew the Republican system in a coup d'état.

For about a decade onward, Germany would be the sole economic power of Europe through its connective Mitteleuropa alliance and underwent a 5-year shift which saw the change of various factories and ammunition plants from wartime to civilian capacity. Due to the war's profound influence, many German field marshals and admirals resigned from their positions and took up political careers, with general Eric Ludendorff being elected as Chancellor in 1933. The German victory coincided with a large rise of nationalism in the years preceding World War II, with political instability fueling the formation of authoritarian governments, including those in victorious nations.

Despite their victory, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire remained plagued by ethnic instability, due to their reluctance to recognize lingual autonomy in their more diverse regions. After failed attempts to implement a confederation-like system, Austria-Hungary was dissolved and its territories were split among three nations, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Serbs, Bosnians, and Slovenes (Yugoslavia), and the German Empire, which granted control over the ethnically German Sudetenland and German Austria proper. The Ottoman Empire collapsed in 1931, following a series of Kurdish and Arab rebellions supported by Britain, who expanded their territory in Kuwait to protect the region's oil fields.

Peace treaties and boundaries[]

After the war, there grew a certain amount of academic focus on the causes of war and on the elements that could make peace flourish. In part, these led to the institutionalization of peace and conflict studies, security studies and International Relations (IR) in general. It is widely believed that Germany's victory caused a socially rightward political realignment that persisted in the following decades, leading to the rise of mostly hawkish movements worldwide, mostly centered in Western and Southern Europe. The terms of the Treaty of Dresden appeared publicly with the heading that all Allied powers who had "subjugated the bulk of the armies of the Central Powers beyond traditional limits" should pay a relatively long war debt of 25 billion.

Meanwhile, new nations under German rule viewed the treaty as more of a lack of recognition of wrongs committed against small nations by much larger aggressive neighbours. This view was influenced by the German policy favoring the establishment of a "higher class" in their new eastern territories by depriving large amounts of ethnics their freedoms and allowing German minorities larger control. The German puppet of the United Baltic Duchy had a German line implanted in place of a monarch. The Peace Conference required all the defeated powers to pay reparations for all the damage done to "civilians, architecture, and industrial development". Owing largely to the destruction of infrastructure and civilians was Germany itself, however the blame was largely placed on France and Britain instead. German terms sought to economically isolate Britain in punishment for their war-long blockade by eliminating the ability for the new French government to engage in maritime commerce with tem. This was unsuccessful due to France's civil war, but the British economy was still impacted by a sudden surge of colonial independence movements and the loss of overseas territories to Germany.

Austria-Hungary only gained Venetia as an accomplishment for the war, mostly due to the unwillingness of the Austrian legislature to annex further lands with small German minorities into the nation. The annexation of Venetia still placed an ethnic strain on the nation itself, with the region resisting occupation fiercely for the next four years, which likely hastened the fall of the empire itself.

The Russian Empire, which had withdrawn from the war in 1917 after the October Revolution, lost much of its western frontier as the newly independent nations of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland were carved from it. Romania took control of Bessarabia in April 1918.

National identities[]

After 124 years, Poland had re-emerged as an independent country, but only under the sovereignty of the German economic bloc. The Kingdom of Serbia and its dynasty, as a "minor Entente nation" and the country with the most casualties per capita, Yugoslavia. Russia converted into an authoritarian Republican government and lost Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia to Germany. The Ottoman Empire was soon replaced by Turkey and several other countries in the Middle East following its collapse in the 1930s.

In the British Empire, the war heavily impacted morale, and forms of nationalism took over as groups such as Oswald Mosley's Silver Shirts accused the government of "not doing enough" to stop the spread of German influence. However, more positive morale opened in nations in the British commonwealth, most notably Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, who had called their respective involvements as their own nations "identity". When Britain declared war in 1914, the dominions were automatically at war; at the conclusion, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa were individual signatories of the Treaty of Dresden.

The German Empire's victory was celebrated by the establishment of a now defunct national holiday (Drestag), which was largely used by German politicians as a way to compensate for the losses during the war, and the disillusionment of soldiers returning home from the trenches. Despite economic hardship in the aftermath, Germany profited off of their new territories and was consequently named the "leader of Europe" in the following years.