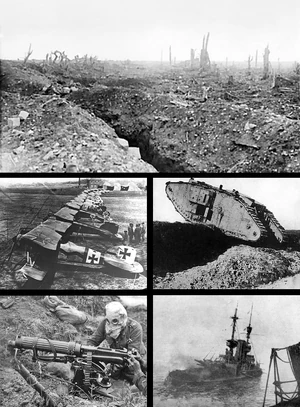

World War I also called the Great War or World War prior to 1939, and First World War interchangeably since then, was a global military conflict fought around the world but centered in Europe between July 28, 1914 and November 11, 1918. It involved a large number of the world's great powers who fought in two opposing alliances, the Allies with Great Britain, France and Russia, and the Central Powers, composed mainly of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire. Ultimately almost all of Europe was drawn into the war and in total around 70 million soldiers were mobilized in one of the largest wars in history. More than nine million combatants were killed with significant civilian casualties also suffered on both sides due to atrocities committed by the combating nations. The high casualties are attributed to new technologies and methods of war, old tactics from the 19th century early in the war and an increase in technology without corresponding improvements in protection or mobility for soldiers.

Long term imperialistic and nationalistic goals are considered to be the main causes of the war, as it broke out between Serbia and Austria-Hungary in July 1914 after Serbian nationalists killed a prince of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The subsequent political alliances that entangled Europe and Asia lead to the wide-scale of the war as Austria-Hungary posed to Serbia an outrageous ultimatum, which lead to a declaration of war by Austria-Hungary, Russia declaring war in Serbia's defense, and the remainder of joining nations did so early in the war after this. The German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Italy formed the Central Powers, named so because of their position in central Europe. The Entente (Allies) were made up of Great Britain, Russia, France, Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, and eventually Japan, Belgium, and Romania.

The war opened on July 28, 1914 when Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia, then followed by a German invasion of the neutral nations of Belgium and Luxembourg to achieve the Schlieffen Plan and invade France. After the German march on Paris was halted at the First Battle of the Marne River, a series of trench line defenses spread across Western Europe and turned into the stagnant trench warfare that would go on to define the war. In Eastern Europe the war was much more dynamic as lines constantly shifted between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. After the a subsequent Allied failure to knock the Ottomans out of the war in the Gallipoli campaign, the war spread to the Middle East as the British and Ottomans with their German allies fought a battle over Mesopotamia and Egypt. Eventually in 1917 the Russian Revolution knocked Russia out of the war, followed by the German Spring Offensive of 1918, which subsequently knocked France out of the war, the Allies fell one by one. By the summer of 1918, only the United Kingdom was left on the Allied side, and they themselves surrendered after an extensive German bombing campaign and naval and submarine blockade.

After the war the Russian Empire, Kingdom of Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg all ceased to exist. The Treaty of the Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919 in the Palace of the Versailles in France, dictated by the victorious Central Powers. The political map of Europe changed significantly as new nations were carved out of Eastern Europe and Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary made gains in the Balkan Peninsula. The reparations and economic and political backlashes that would occur following the Treaty of the Versailles would eventually go on to be some the recognized main causes of the Second World War.

Background

The background of the First World War goes back to the Napoleonic Wars of 1803-1815 when Napoleon spread the First French Empire to its maximum extent and with it the Napoleonic Code and lead to a flare in nationalism. As nationalism spread it would reach far and wide into Europe, especially in the ethnically-diverse Balkan Peninsula dominated then by the Austrian and Ottoman Empires. As Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece achieved independence in the 19th century and the Hungarians achieved co-habitation with the Austrians in the establishment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Eventually it was these nationalistic tensions in Southern Europe that would explode in 1912 into the Balkan Wars, one of the direct causes of the First World War.

After the Young Turks Revolution of 1908 forced the Ottoman Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, to reinstate the Turkish Parliament, the enemies the Ottomans had garnered or simply pondering European nations looked to the Ottomans as an easy target. Later in 1908 the Bulgarians declared their independence from the Ottomans which they had been guaranteed in the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano, as the weak Ottomans had been unprepared to stop them, the Bulgarians gained independence and were rapidly recognized by the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary. Italy then saw this as their chance to attack the Ottomans and seize Libya from them, and in the subsequent Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, the Italians gained the Turkish provinces of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan along with the Dodecanese Islands in the Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey was humiliated by yet another quick defeat by a young European nation, but by far the worst was yet to come.

In 1912 the Balkan League composed of Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece took advantage of the Ottoman's ill fortune and began the First Balkan War. They quickly defeated the Ottoman Army, by this point severely ill-equipped and untrained in warfare. The Peace of London that followed allotted most of the Ottoman territory left in Europe to the victorious powers, but left Bulgaria, by far the most powerful of the victorious powers, feeling it wasn't being given enough land. Thus they then launched the Second Balkan War, which Bulgaria began to lose after its Army had become overwhelmed and overextended. Germany intervened diplomatically and, with Russia, was able to negotiate the Treaty of Bucharest, signed on August 10, 1913.

Serbia won Macedonia from the Bulgarians in the Treaty of Bucharest, and after this felt more confident in pursuing its nationalist, Pan-Yugoslavic goals. Nationalists look to Austria-Hungary, which was then still home to a significant Serbian population, and sought separation of the Serbian regions in Austria-Hungary from the Empire and to transfer it to the Kingdom of Serbia. Ultimately it was these nationalists that began World War I when the Black Hand organization assassinated Prince Charles of Austria in Sarajevo, Bosnia, by Gavrilo Princip which lead Austria-Hungary to declare the July 28 Ultimatum, which directly lead to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia and the outbreak of World War I.

But another cause was the intertwining alliances built between European powers throughout the 19th century. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars the German Confederation was established as a replacement to the Holy Roman Empire, which Napoleon had dissolved in 1806. It was dominated in the north by Prussia, and in the south by Austria, which inevitably was to end in direct conflict between the two. In 1864, the two engaged Denmark in the Second Schleswig War which won them the province of Schleswig-Holstein, which they ruled co-operatively. In 1866 they engaged in war between themselves in the Austro-Prussian War, which lasted famously seven weeks and resulted in a decisive Prussian victory, allowing them to establish the North German Confederation. Then after the later War of Nations, between Austria, France and Bavaria on one side and Prussia and Italy the other side, Germany united under Prussian King Wilhelm II and the new German Empire.

The alliance between Germany and Italy that resulted became the core of the Central Powers, which would go on to include Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire in 1889 after the Treaty of Budapest. The Allied Powers or Entente was established officially in 1894 when Russia and France cemented an official alliance against Germany. In 1907, the Anglo-Russian Alliance was formed against Germany as well as the United Kingdom had become concerned with the rapid naval growth of Germany's High Seas Fleet which would appear to be trying to challenge the British Royal Navy. It was these alliances that would turn this into a world war, but it was the nationalist fervor and technology of the war that would incur such heavy casualties combined with old tactics. The Germans were drawn into the war by Austria-Hungary, Russia by Serbia, Britain in protecting Belgium, France by Russia, and eventually Italy by Germany. Eventually all of Europe and the Middle East was drawn into the "war to end all wars," and only weak and non-aligned nations like Spain and the Scandinavians were not drawn in. But regardless of any formal plan of attack the war would soon be fought on a scale and in a magnitude that no military planner could foresee.

Western Front

1914

The Western Front opened in Europe on August 4, 1914 well over a month into the war, when the Germans enacted their Schlieffen Plan, developed by Count Alfred von Schlieffen as a way for Germany to easily conquer the French via Belgium and then moving all of their forces East to fight Russia in the case of a two-front war. The plan was enacted as originally devised with a German invasion of Belgium on August 4, coming two days after the Germans invaded and conquered the small nation of Luxembourg. The German invasion plan required that Belgium's neutrality be broken by the German Army in order to attack the French on their left flank. Thus the German invasion of Belgium went ahead as planned, but the Belgian resistance was underestimated by the Germans, and the Germans were held at bay in Germany for one month before they could enter France en force. Belgian forts like Liege, Namur, and those at Antwerp were blown to pieces by the German "Big Bertha" heavy artillery guns, allowing the Germans sweep through the country, leaving only the city of Ypres unconquered by the Germans by October 10, 1914.

Meanwhile, further to the south in the Alsace-Lorraine region, the French Army went on the offensive in mid-August, enacting their own battle plan, Plan XVII. The French Army moved into the German province, with five objectives to achieve, but by August 25, 1914, the French had been beaten back by the Germans after suffering significant losses in the offensive, forcing them to retreat from the province. To go along with this early German success in the war, the Germans besieged Antwerp with the assistance of Austro-Hungarian soldiers from September 28-October 10, 1914, capturing the Belgian capital, and requiring 30,000 Belgian soldiers, one-third of the Belgian Army, to retreat to the Netherlands to the north, which the Germans had not invaded. Success in the war seemed certain for the Germans, and as they steamrolled in France the French Army and British Expeditionary Force retreated to the River Marne in what became known as the Great Retreat.

Then in September came the Miracle at the Marne, the British and French Armies, numbering at just over one-million soldiers, defended the river and Paris itself from a German force of 1,485,000 soldiers. After one German commander, General Alexander von Kluck, divided up part of his force to meet a potential threat to his right flank, Allied air reconnaissance was able to pick up on this gap in the German lines, and attacked, driving a wedge in the German lines. The German Army was close to enveloping the French Sixth Army, but with the assistance of reservists and taxi cars they held out against the Germans, and the German Second Army was then devastated in a night attack by General Franchet d'Esperey and his Fifth Army. The German First and Second Armies looked like they would be surrounded and destroyed, which caused German commander, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, to suffer a nervous breakdown, requiring his generals to coordinate a retreat. The retreating German Army was pursued by the Allies, but they only captured as much as 12 miles (19 km) in a single day, and the Germans successfully withdrew 40 miles northeast to the Aisne River. Afterward both sides dug into their trenches, beginning the trench warfare that would plague both armies throughout the war.

Shortly afterwards the Germans moved in to capture their only unaccomplished objective in Belgium, the western town of Ypres. After the Allies failed to break the German lines at the Battle of Aisne in late September 1914, the Germans moved in to captured Ypres, the remainder of the Belgian coast, and to move in to capture the French Calais region and the ports from which the British were crossing the Channel into. Their maximum objectives were to capture Dunkirk and Calais, but the Germans and Allies knew that Ypres had to be captured first. The Germans flung 5.4 million soldiers to capture the city and the remainder of the Flanders region of Belgium, attack the Allies on their northern flank. German improvements in reconnaissance gave them the advantage in the battle, allowing them to estimate the amount of force the Allies were throwing into the defense, the German offensive action began on October 19 and ended on November 24, at which point the Belgian and Allied forces defending the city surrendered, and the Allies retreated back into France. The city of Ypres was conquered, and the remainder of Belgium was knocked out, requiring King Albert I of Belgium to take what was left of his army and retreat into France.

The Race to the Sea was less successful from that point on as the French and British, having also lost the Battle of Nieuport to the north of Ypres, no longer worried about defending the Belgian coast, which was now all but lost. The Germans moved in to capture Dunkirk and the Calais region, but were then stopped at the Battle of Lille in which the French held their lines allowing them to force a stalemate in the offensive, and eventually by the end of November all mobile movement along the front had ceased and Calais and Dunkirk remained in Allied hands, keeping British supply lines open. Both sides then set themselves up for a long defensive battle, which only broke at Christmas. On Christmas Day, 1914, soldiers from sides met in No-Man's-Land, the land between two trenches, and celebrated with exchanges in gifts like boxes of cigarettes, alcoholic drinks, and even souvenirs from home. Although it was a nice break in the harsh fighting, both sides would not celebrate Christmas along the front again until the war finally ended in 1918.

1915

The opening of the new year in 1915 was met with anything but joy on the Western Front, but as the Allies began to outnumber their German counterparts, a breakthrough appeared to be on the horizon. In the past four months of fighting Germany had gained control of all of Belgium and trenches now lay across every mile from the Swiss border through France. The year opened with an Allied offensive on the German-occupied city of Champagne-Ardenne, which only resulted in a stalemate, but set the stage for the rest of the year as both sides incurred high casualties of around 90,000. The Allies then launched a counteroffensive into Southern Belgium in an effort to reconquer the strategic city of Ypres to open the Belgian campaign again. Eight Allied infantry divisions advanced on the city defended by seven German infantry divisions, with the Allies attacking strategic areas like St. Julien and Frezenberg in late April and early May, but then the Germans counterattacked. By officially being the first users of poison gas on the Western Front (they had already used it against the Russians on the Eastern Front), the Germans had incurred a new type of warfare, the kind with biological weapons. The Germans used chlorine gas shells, which was spread by the air and pushed towards the Allied lines, forcing greater casualties on the Allies, leaving some of them blind. After they were beat off and with poison gas used against them, the Allies retreated back to their lines, with the Germans failing to pursue them.

Then French General Philippe Petain prepared the Allied armies for another attempt at breaking the German lines at Artois. Although he had originally made some good advances, Petain's army was slowed down, and eventually pushed back, forcing another stalemate by the time that the offensive ceased on June 18 after over a month of fighting. The French Army under Joseph Joffre then launched another counterattack against the Germans in late September at the Second Battle of Champagne, which began rather successfully. The French made modest gains as their artillery pounded the German lines for three days prior to the beginning of the offensive. But the day after the offensive began, reserves arrived and the German reinforcements stopped the French advance, eventually ending the offensive on October the 6th. The attack on Champagne began again on October 30, but the initiative that the French had a month earlier was gone and they failed to make any gains, actually losing ground to a German counterattack. The French offensive battle plan for Champagne was finally ended on November 6, after the fighting neither side had advanced anywhere over a mile.

Meanwhile, further to the northwest in France, the British launched an offensive on the town of Loos, with the British Expeditionary Force being backed by reinforcements from the British Indian Empire. The British used two technologies to their advantage, using their own gas weaponry and planting mines under German lines for the offensive to exploded at zero hour. Ultimately the British flung 140 tons of chlorine gas at the Germans, but anti-gas methods, mainly early gas-masks, allowed many more Germans to survive the attacks. But the British did break through the weaker parts of the German lines, capturing the town of Loos, but German defenses geared up for a counterattack, and on September 28 the British retreated back to their lines. The Germans then launched a counterattack against the British lines on October 8, but failed to make any major gains and abandoned the offensive by nightfall due to high casualties. The British attempted a final offensive on October 13, which ended in failure due to lack of equipment, and heavy October and November rains prevented either side from launching another offensive. Ultimately, British Field Marshal Sir John French was fired as the head of the BEF as a result of the battle, as British losses had been twice the German losses, 50,000 to 25,000.

The last Allied attempt to break the German lines in 1915 came at the Third Battle of Artois, a combined Anglo-French force under the separate command of French commander Auguste Dubail and British commander John French launched an offensive to destroy the German Sixth Army under Bavarian Crown Prince Rupprecht. It was the last attempt by the Allies to exploit a numerical advantage over the Germans in 1915, but would ultimately end in failure. Originally meant to be concurrent with the attack on Champagne, the goal was to capture German rail supply centers at Attigny and Douai. Beginning with a four-day artillery bombardment, and after the offensive began on September 25, the French capture the town of Souchez on September 26. But they then made little progress in their attempt to seize the town of Neuville-St Vaast, and overall the Allies failed to break the German defensive lines and could not break through the German lines.

By the end of 1915 the Allies had failed to capture any major objective and had failed to use their numbers to achieve any great breakthrough of the German lines. In December 1915 as the BEF was in ruin, Sir John French was sacked as the commander of the force and was replaced by Field Marshal Douglas Haig. The Germans spent the winter of 1915 repairing their defenses and replacing their losses with new reservists, preparing for the up-and-coming action that was to take place in 1916.

1916

After the long stalemate of 1915, which not only introduced poison gas to the Western front, but ended with little-to-no gains being made by any fighting power, the combatants were ready to use whatever means necessary to achieve a breakthrough. German General Erich von Falkenhayn wanted a way to bleed the French dry, to attack an objective the French would blindly defend, and force them to suffer massive casualties in its defense. After the sieges of Liege and Namur, the French had seen that heavily fortified redoubts were defenseless against German heavy artillery guns, and so throughout 1915 the French depleted Verdun of 50 batteries and 128,000 rounds of artillery ammunition to be moved to the offensive to the north. As this process was still going on at the end of January 1916, the Germans selected Verdun, also a strategic railway location, as the target for Falkenhayn's "bleed them dry" offensive. The fact that it was surrounded on three sides by the German Army and had only one major supply line to the French Army was only icing on the cake.

The German Army moved in on Verdun on February 12, 1916 and began with a ten-hour artillery barrage that dropped 1,000,000 shells on the Verdun fortifications. This was followed by an attack by three German Army Corps on Verdun who used flamethrowers and storm troops to rid the area of what their artillery had not. Within 10 days the Germans had advanced 3.1 miles (5 km) into the Verdun sector, and it was only then that due to failure in the French communications did the upper command of the French Army realize the magnitude by which the Germans are attacking Verdun. The French then tried to mount a counterattack on February 23, only allowing the Germans to launch their own counterattack and capture the town of Bois de l'Herbebois. By the next day, February 24, German forces had reached the center of the French fortifications, Fort Douaumont. A raiding party lead by Captain Hans Joachim Haupt and Second Lieutenant Cordt von Bradis made up of 19 officers and 79 soldiers lead a successful raid, for which Haupt and von Bradis were awarded, which captured the fort.

Soon after, Philippe Petain took control of the Verdun sector command and reinforced it with the French Second Army. Petain ordered more defenses to be built-up within the center of the fortifications to allow for a better defense of the area. Eventually by the end of February the German offensive had slowed down after the Germans take the town of Douaumont, allowing the French to trickle in 90,000 soldiers into Verdun and 21,000 tons of ammunition to their artillery. The Voie Sacree (Sacred Way) allows the French to continue a steady flow in the defense of Verdun, but the Germans are reinforced in mid-March by two more army divisions, keeping the balance of power. In late March, the French launched a counterattack on Douaumont, which was preceded by a moderate artillery barrage, but ultimately the defense of the town was a German victory and the French lost four infantry regiments in the attack. As early April came around, the reinforced Germans stormed and captured both the Bois des Corbeaux and the Le Mort Homme. The French had lost crippling casualties defending these positions, and the Germans are certain their "bleed them dry" strategy is working.

After the Germans capture Cote 304 soon after the fall of Le Mort Homme, the French launch another counterattack on Douaumont in May, but again fail with high casualties. In late May the Germans launch a maneuver to cut the French off from behind, and to finally close their supply lines. The massive assault uses four divisions of infantry and is launched after a 12-hour artillery barrage, but the French, knowing their dire position, put more infantry on their rear to defend from the German attack. The Germans make good gains against French reinforcements, and the French begin to rush to put as much supplies around Verdun as they can before they are cut off. The Germans break the French defenses and the French city of Verdun is cut off from ground supply lines on May 21, 1916. The French then prepare to begin dropping in supplies by air, a strategy that had never been tried before, but decide to turn down this strategy by declaring it too risky. Instead the French decide to prepare for a counter-offensive around Verdun using reserves that have been defending the border with Italy in the case of the latter's attack.

As June rolls around, the Germans prepare for a renewed offensive on the French rear, and in anticipation for this offensive they reinforce their Army with 150,000 new soldiers to the front, preparing to combine storm troops, heavy artillery, and high numbers to overwhelm and obliterate the French defenses. The offensive begins on June 6, beginning by firing 116,000 gas shells at the French lines, claiming 1,600 French lives. The Germans first moved in on the flanks of the French rear, attacking the town of Dieue on the French right flank and the town of Montzeville on their left flank. The German offensive rolls over the French defenses and German soldiers prepare no longer for a frontal assault on Verdun, but now rather a rear attack. German soldiers press on the French flanks, and Petain, realizing this may be the decisive fight for Verdun, declaring to his soldiers "Ils ne passeront pas!" (They shall not pass) But the Germans continued to fight despite the French commander's words, and as the German pincirs met up at the roads where the Sacred Way had once lead to the city of Verdun.

After the offensive ended at the end of June, the Germans had failed to totally knock out the remaining French defenses, but had made considerable gains, leaving at most 7 miles between the lines by the beginning of July. Then in the dense July heat, the French launched a massive counterattack, including an entire French Army with which to either break the German lines and force a retreat, or the more likely event of breaking through to Verdun, allowing the remaining French troops to withdraw, and then retreating before the Germans could attack again. The offensive later turned into a complete debacle as the French failed to gain more than a mile of territory by the end of July, a German counterattack ultimately forces their defeat and French inside Verdun grow hopeless of victory. Thus in August of 1917 the final German attack blasts into Verdun, and at last the city falls to the German Army, and Germans win their "bleed them dry" victory. The Germans have lost 305,000 soldiers in the battle, while the French have lost over 670,000 soldiers, dead, wounded, and few captured, in the fight.

Meanwhile the British have launched their own offensive against the German Army farther north along the Somme River. As their French comrades moved towards defeat in the Verdun sector, the British launch the Somme Offensive on the Germans on July 1, 1916. Douglas Haig, the new commander of the British Expeditionary Force, made it to be the British effort in a combined Allied offensive on both the Western and Eastern Fronts to break the German lines. The Allied plan was revised after the Battle of Verdun opened on February 1, 1916 as the French no longer were able to put a great force into the battle, but still made a significant contribution. The British offensive began when the British set-off 40,000 lbs of mines beneath the German-controlled Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. After the shattering sound of this offensive was made, thirteen entire British divisions launched the beginning of their offensive.

After communication failures occurred the battle eventually advance began to turn into a complete failure, which required the use of British Commonwealth reserve units. But as these foreign soldiers marched into battle, they were cut down by German machine-gun fire. Famously the Tyneside Irish Brigade Regiment marches against German lines in full view of their machine-guns and is entirely cut down. The only assets to the British attack were surprise and numbers, allowing them to make slight gains against the Germans. But still then the British advances were very minimal and Douglas Haig pondered the idea of ceasing the attack and launching an offensive elsewhere. But as he decided to continue the attack at the Somme, the British continued to lose casualties, eventually losing around 60,000 total casualties in one day. July 1st was to become known as the "bloodiest day in the history of the British Army."

Throughout the next two weeks, the British and French continued to push their offensive against the Germans along the Somme River. Although the German General Staff had been set off-guard by the surprise offensive, Falkenhayn pushed to make sure the Allies did not break through. As the Germans had not planned on being on the defensive at any great extent in 1916, Colonel Fritz von Lossberg saw it as the perfect time to enact a new "defense in depth" strategy. German reserves would be held behind the front in defensive lines, while lighter amounts of soldiers would be placed on the front and this would ensure less casualties. The British had failed to make any great gains on the first day as they had hoped, but Haig saw modest gains being made in the South, and so saw to it that they focused there in the coming days. By July 3rd, the Allies had succeeded in partially capturing towns in the north, but witnessed greater success in the south. By July 14, 1916 the German's southern flank was hard-pressed while the British were held down in multiple forests to the north. Within just two weeks of fighting, with tens-of-thousands of deaths, the Allies had only gained six miles in their advance.

The British then planned for a breakthrough attack in the north at Bazentine Ridge, and after a lull in the fighting between July 11 and July 14, that is where they attacked. The British objective was to capture the towns of Bazentine le Petit and Bazentine le Grand, and the German objective was to make a decisive defense which could force the British into retreating by mounting casualties. The British won early success by launching a creeping barrage of artillery, which covered the British advance right up until they reached the German trenches. The British had managed then to punch a gap in the German lines, but then they failed to exploit it, and this was then followed by a failed cavalry charge. But here the Germans had the advantage due to "defense in depth," forcing on the British enough casualties that they did retreat, and were then followed for a short while by a German counterattack. The German counterattack in the north then pushed the Allies back to their lines held on July 14, meaning the Allies had totally failed.

The British then launched an offensive on the town of Pozieres, again the British were looking for a breakthrough to occur in the north. The British called on the power of their Anzac Corps, using soldiers of the Australian Divisions to launch the offensive. Beginning on July 23 at night, the offensive was also an early success after Major General Harold Walker had asked for emphasis on preparation and bombardment before the offensive. Although their first objective was achieved, the attempt to capture the German's second line had failed, and sat through three other British attacks until August 3. Then the Germans launched their own counterattack on the British, pushing them back again their original positions, further frustrating the British High Command. Then at last on August 5, the British made one final massive push on Mouquet Farm near Pozieres, but after another month of fighting for the territory with the Germans, the British were again forced to retreat.

The remaining month-and-a-half of fighting between the Allies and Germans was marred by attrition on both sides, and eventually later on by a British break-down in organization. In early September the British had launched two indecisive attacks on the towns of Guillemont and Ginchy, and much of the remainder of the time was fighting in the forests that dotted the German northern flank. In late September, the British, in need of a breakthrough, deployed two "tanks" in offensive actions against the Germans. Although they proved to be very big on scaring the Germans, they both had broken down on the same day they were deployed. Eventually a November chill set in and British finally gave up on breaking the German lines. The Allies had thrown 1.2 million soldiers against the Germans in an offensive that had cost the Allies 630,000 casualties, to German losses of 425,000. It was suggested by the German command to the General Staff that they retreat back to the Hindenburg Line defenses, prepared 40 miles (64 km) east, but the Germans decided to reinforce their lines instead, believing correctly that the British would not attempt such an attack again for quite some time.

The Germans had succeeded in forcing massive casualties on the French and British Armies in 1916, far greater then the Allies had on them. The French had made a dire mistake in moving soldiers from the border with Italy in the failed Verdun counter-offensive. Soon after in February 1917, the Italians joined the fight on the Western Front, and the British and French were forced to move roughly 600,000 reserve forces south from the fight with the Germans now to hold off their new enemy to the south.

1917

As the year opened, the Italian Army invaded France, beginning with a force of roughly 1.2 million that wasted no time after launching their invasion in mid-March, 1917. The first couple major objectives captured Monte Carlo, Monaco, and Nice, which quickly turned the invasion into a high priority for the defense of France. Now 800,000 Allied soldiers had to be moved to assist 250,000 French soldiers already on the border in reserve to hold off a possible Italian attack. By the middle of April the Italians had reached as far in as Toulon, but came just short of that objective, and their overall objective of Marseille. The Allies were supported by soldiers from Portugal who were vital in containing the Italian assault, but now the Allies were fighting a war of attrition on two fronts. The offensive was contained by the beginning of May and support of Portugal was the decisive force in this, allowing for the Allies to keep up to 200,000 soldiers on the Northern front.

Those soldiers became vital on April 9, as it was on that day that the Allies launched their latest counterattack on the German lines at Arras. The British launched the attack as a broad frontal assault between the cities of Vimy and Bullecourt, preparing the German lines for attack first with the usual massive artillery assault. Then Canadian forces marched out to capture the strategic point of Vimy Ridge, while British forces pushed on to the Scarpe River. But while the British made significant gains on Vimy Ridge, the British and Canadians were frustrated by repeated and failed attempts to break the German lines with their defense in depth. While the British were able to capture the Scarpe River by April 14, the Germans succeeded in forcing the British to stretch their communication lines. The last part of the British offensive was against Bullecourt, in which two whole divisions took place, one British, one Canadian. This was also a notable use by the British of tanks, 11 of which were deployed for use at Bullecourt. The tanks were delayed by weather on the 10th of April, but the British used them in their attack on the 11th. But German defenses managed to hold off the British attack, even with their tanks, two of which they then captured, studied, and used in battle with the German Iron Cross painted on the sides.

The British launched the second phase of the battle on April 23, launching a second offensive on the Scarpe River towards Vis-en-Artois. Although Commonwealth forces did capture the town of Guemappe, but suffered heavy casualties when they tried to push to Vis-en-Artois. The Germans then counterattacked and were able to push the British back, eventually slowing down after the British were reinforced. Eventually any further British attack on the Scarpe was called off on the 24th of April. The British then launched on April 28, the Battle of Arleux, hoping to secure their south-eastern flank, but again failed to do so, allowing for a German counterattack. The Germans then launched their main counterattack on the British gains, making Bullecourt their first priority. The Germans took two weeks to take back the town, but eventually when the British retreated from it on May 17, the Germans believed they had achieved a breakthrough. A massed German counterattack succeeded in taking two miles of British-controlled territory by the time the offensive was stalled by British reinforcements on the 29th of May.

The French then launched their own offensive on the German lines, aimed towards capturing an 80 kilometer long ridge, occupied by the Germans who used the quarries that protected them from French artillery. While the British and Canadians were busy attacking German lines at Arras, on April 16 the French threw 19 divisions at the German lines along the 80 km ridge between Soissons and Reims. The French used a strong artillery barrage to precede their attack, but as the Germans were able to once more hide in their quarries, the attack was to no avail. As they had been warned of the attack by the French artillery, they were able to concentrate their machine guns on high ground, overlooking the valley of the Aisne River. The German 7th Army was left to defend the valley, and on the first day of fighting did well at doing so as the French lost 40,000 men in all casualties to the Germans along with 150 tanks. Their attempts at using a creeping barrage were poorly executed and failed to cover the French advance as they moved towards the German lines.

The French then launched a second assault on the 17th, with the French Fourth Army making the push against the German First Army east of Reims towards the town of Mornvilliers. But even as the Germans easily repelled the assault, the French continued their attacks towards the Aisne River continued until the 20th of April. Some small gains were made to the west of Soissons, however, the attacks were continuously scaled back and the Germans were soon able to retake their losses. Eventually the French had gained only 4 km in the whole attack, but at the loss of 120,000 French soldiers to the German losses of 40,000. The attack had been a failure, but seeing as their attack towards Aisne and Arras had failed, the Allies against looked towards Ypres for their breakthrough attack.

The Third Battle of Ypres began on June 7 with the Allied attack on Messines, which held a ridge that created a massive ridge that made the natural defense of Ypres. The British began the battle of Messines by detonating 19 mines underneath German lines, which gave them not only surprise, but also a gap in German lines to attack through. Artillery fire, which had ceased at the point the mines were blown up, then continued again to keep the infantry protected with a creeping barrage. British and ANZAC troops advanced on Messines on three sides, overrunning German positions all over Messines, and forcing the Germans to surrender in droves. Five kilometers north, Scottish soldiers moved in towards the center of Messines, facing serious defenses along the Ypres-Comines canal, which itself was eventually captured. On June 11, the British were stopped just short of their second objectives, and the Germans launched a wide-ranging, but futile, counterattack. On June 14, the Battle of Messines ended, and the Allies moved in to again attack Ypres.

The Third Battle of Ypres began on July 31, launching attacks on Pilckem Ridge, the Allies besieged the ridge, throwing masses of artillery against the area. Eventually that too fell to the Allied advance, and by August 10, the city of Ypres was under direct fire from the Allied assault. Allied soldiers destroyed German forces at numerous battles along Ypres' defenses, but eventually their advance came to the town of Passchendaele. The British threw in five divisions, backed by three Australian divisions and 11 New Zealand divisions, launched the attack on October 12. The ground on which they advanced was horrid as the Commonwealth soldiers advanced, as bodies were left there after suffering from German sniper fire. Bad weather had made it muddy and wet, and the British had a hard time getting their artillery into position. Eventually the assault on Passchendaele turned into a quagmire, the Australians and New Zealand troops were unsuccessful in reaching their objectives and the advance eventually stopped. The Germans saw a chance to strike, and 60,000 German soldiers were brought in to support 35,000 front line soldiers for a renewed counter-offensive. Eventually the Second Battle of Passchendaele was a strong German victory, pushing the British back and capturing tens-of-thousands of Allied soldiers.

Eventually supported by 6 more divisions, the German offensive pushed at the over-extended Allied flanks, crushing them with artillery and requiring Douglas Haig to order the British to retreat on October 23. The Germans launched a general offensive, hoping to achieve a breakthrough by constantly pursuing the Allies as they retreated. Soon after, the British had retreated and a final German push knocked them out of Belgium, now once and for all. As October turned into November, the Germans advance stalled and ceased by around November 6, leaving the German General Staff disappointed but satisfied that they had dealt the Allies another decisive blow. Overall the Allied casualties were 400,000 killed or wounded, with 120,000 captured to German losses of 300,000 of all kinds.

But although the Allies had been defeated by the Germans, they had one more offensive action planned for the city of Cambrai. The British attack on Cambrai began on November 20, which began with a massive barrage by over 1,000 guns on German defenses along their lines. The British creeping barrage covered their soldiers for the first 300 yards ahead of their advance, but the advantage was now held by the Germans, who had anticipated the attack with superior intelligence. The battle opened with an attack by six entire infantry divisions backed up by 437 tanks, advancing five miles into the German lines. Eventually British tanks advanced beyond their infantry, and were then torn to bits by powerful and accurate German artillery, who had grown now adept to use anti-tank shells. Eventually destruction and breakdowns piled up and the British tanks advance stalled, waiting for the infantry to catch up. As the British swept through towns like Havrincourt and Graincourt, they reached the maximum of their advance. 180 tanks were out of action at the end of the first day, with only 65 being destroyed and 115 having broken down. The British infantry losses were light for the first few days as the tank battalions suffered the majority of the casualties.

Final British efforts reached out at Bourlon Ridge, but soon after the Germans sent in reinforcements and fighting began again on the 22nd after slowing down on the 21st. After the British infantry rushed to meet up to the advance of their tanks, they were setting themselves up for disaster. Their salient was exposed to German artillery fire, and they made few advances as the 23rd and 24th of November rolled around. The British began to suffer about 4,000 casualties a day, but the British now held a salient 11 km by 9.5 km by the time the offensive stopped on November 28.

But as the British stalled, the Germans geared up for a counterattack as reinforcements were rushed to the front. Twenty divisions of the British Commonwealth Army now law within the salient, the German thought that if a successful breach of the salient could be achieved, the British divisions would be exposed and defeated. The Germans prepared for a short, but precise and rapid, artillery assault on the British lines and following this up with a rapid assault of General Hutier's Storm trooper tactics. The storm troops attacked the British salient on its flanks at Havrincourt and Gonnelieu, they made quick advances by attack in groups as opposed to waves and bypassed strong enemy opposition. The German advance was swift and in their sweep through the British lines, capturing the commanders of the 12th and 29th British Divisions. The advance that followed enveloped the 12th and 29th Divisions, resulting in many British soldiers being captured and the British rear being cut off. The German advance spread broadly across eight miles, and the German General Staff was excited to learn that it had come close to capturing the historical and strategic town of Metz. Eventually only nightfall would stop the German advance, and while much of 12th and 29th Division was captured, the remaining divisions were able to retreat south. By December 3, the pressure of Germany's advance had successfully pushed the British beyond St. Quentin Canal. 75,000 British soldiers were killed in the battle, 25,000 were captured, while roughly 45,000 German casualties of all kinds were suffered.

1917 had given both sides valuable lessons, the British and French ceased offensive operation after the loss at Cambrai, but the Germans had learned even more. Cambrai had shown the Germans the power of their short and rapid artillery barrages, the strength of storm troops, and especially the capabilities of tanks. But before the Germans were ready to deploy their own tanks, they had to prepare their soldiers not only in the ways of battling in tanks but in maintaining them. The Germans meanwhile were now preparing for a massive offensive in the spring of 1918, using their combined force of tanks, air power, and especially reinforcements as they rapidly moved German soldiers from the Eastern Front to the Western Front as Russia collapsed to Soviet revolution. The Germans turned their efforts over the winter to creating tanks and transporting troops, little did either side know that next year the war would be over soon.

1918

On January 6, 1918, the Netherlands entered the war, as the British had hoped that when they could gather their forces up enough to push for a new offensive on the Germans, that having the Dutch to launch a pinsir movement on German-occupied Belgium would prove a decisive force by which they would then be able to force Germany into an armistice. Little did the British or Dutch know that the Germans were themselves preparing for a massed offensive across Northern France, whose goal was to push the Allies into one great defeat, and force the French to surrender. The Germans were prepared to use combined arms tactics, using a combination of co-ordinated assaults with air power, infantry, and tanks in one big offensive. They moved fifty divisions within Germany's borders from the Eastern Front to the Western Front in preparation for the attack. The Germans had been fighting a war of attrition for years, now they were ready to strike a decisive blow.

German A8V tanks rolling in line to prepare for the Spring Offensive.

The introduction of the Netherlands into the war in early 1918 had been unexpected was not inconvenient, the German General Staff, some still serving since the Dutch-German War, were happy to see all of Germany's enemies in Western Europe defeated in this offensive. Two field armies were prepared to strike into the Netherlands, this time from north and south rather than east and north as had been done thirty years earlier. The Germans had also at this point been drawing up the terms of a treaty to be signed after the war ended, and prepared to make the Netherlands into a client state along with Belgium. The German Armoured Battalions were equipped with two new tanks, the A7V and A8V, to be at the helm of this offensive. The Deutsche Luftstreitkrafte (German Air Force) had become adept to their fighting air tactics with planes like the Fokker D.VII and Albatross D.III, and using bomber and ground attack aircraft like Gotha G.V and AEG G.IV.

The Allies had tried to prepare for a likely German offensive in 1918 by employing the defense in depth concept to their own lines to a degree. Their front line was defended by snipers, patrols, and machine-guns posts meant to slow down or stop any infantry assault. Behind this Allied soldiers were held in the "battle zone" where they would be forming the majority of their resistance, behind the front line, and hopefully out of the range of the German artillery fire. Defenses were widely unprepared in this concept, however, with some areas being very lightly adapted to the new defense tactics. Germany began moving its soldiers into place in late January, mid-February for the most part, prepared to break into northern France, seize Paris, force the French into surrendering, while also invading and overwhelming Allied defenses in the Netherlands, forcing them to surrender quickly and avoiding another lengthy invasion. Although the German offensive action against Britain was still in the planning stages, the Germans also hoped that if France was defeated rapidly enough that the British may then sue for peace as well. By March 20, all of the German forces were in place for the offensive, all they waited for now was the final order to go "over the top."

Operation Michael, as the Germans had codenamed it, began on March 21, 1918 with the German Army crossing the St. Quentin Canal along their front lines. The German guns hit British positions about 4-6 kilometers out and at around 4:35 they began their heavy barrage along a front of 40 miles (64 km). Mortars, mustard and chlorine gas, tear gas, and smoke canisters were fired across the British front line, a total of 1.1 million shells in the span of five hours hitting an area of 150 sq miles. The British suffered 7,500 casualties along their front lines in the biggest barrage of the war, and as they had been anticipating an attack for a while, the massive bombardment was the greatest surprise. After the Germans finally crossed over the St. Quentin Canal, they pressed the defenses of the British Third and Fifth Army, forcing the British to retreat. To the north, the Flesquieres salient, defended by the 63rd Royal Naval Division, was broken and smashed back, and the Germans pushed the British back by weight of power and numbers.

By the second day of fighting, British troops across the front were in retreat, while maintaining a fight in whatever regions they could. As disaster loomed and the British Army retreated to meet up with reinforcements to the west only small pockets of British and Canadian soldiers were left along the lines to fight the German onslaught. While many British maintained a fighting retreat, some corps of soldiers had begun to fall back to as far back as the Somme River. Eventually on the 22nd the Germans had succeeded in separating the Third and Fifth Armies, against Haig's orders that they were to keep in direct contact with the rear lines at whatever cost necessary. The Germans then moved in to crush the Third and Fifth Armies, who, facing encirclement and imminent, surrendered en masse on March 25. The Allied armies, facing defeat, now retreated back to the Somme River, several miles behind the front line.

The Allies, as they fell back to the Somme River in the west, also faced defeat to the south as German soldiers pushed to break the Allied lines and hurl at their first major objective, Compiegne. German tanks moved in an armored salient, supporting infantry, and having their path paved out by a creeping barrage that moved them steadily towards their objectives. Their other main objective was at Amien, if Amien could be captured then the British and French Armies would be divided, but first they had to break the British defenses at Alberts. The town of Alberts was defended along its lines by only three British divisions, but they put up a strong defense against the two German Army Corps that they had coming their way. The Germans assault on Albert began on March 28, and with another successful maneuver of creeping barrage, combined with tanks and infantry, the Germans swept into Albert. Within four days of fighting the British had withdrawn from Alberts after suffering high casualties and the Germans captured the town.

Meanwhile, two German armies moved south to Compiegne and the battle over the city is primarily recognized to have begun on March 30. The Germans pushed into the city, with three tank battalions at the helm of the offensive, and three corps of infantry in support of them. Germany's rapid artillery assault proved to be a major force in the battle, as they assaulted the Allied lines with almost 4,000 guns to precede the assault. After the bombardment ceased a series of gas shells were dropped along the Allied lines, which coupled into heavy Allied casualties as the British had been ordered to mass up in their front trench line for defense against the German's main assault. After the gas lifted, the German Sturmtruppen divisions began their attack on Allied defenses, which had become spread thin. The attack opened up a 40 km-wide gap in Allied lines, using their tanks to exploit the breakthrough, and then smashing through eight Allied divisions in the process. At the end of the battle on April 6, the Germans registered 50,000 captured Allied soldiers, 800 captured Allied field guns, and a wide gap opened by the German tanks which the infantry could now exploit. The Germans were now just 40 miles from the outskirts of Paris.

As Compiegne fell, the German offensive began to engulf the the remainder of the River Somme in one last final sweep to take Amiens. After reinforcement the city was defended by six Commonwealth divisions, but was being attacked by ten German divisions, with four in reserve, supported by around 243 tanks. The final plan to begin the offensive revolved around the use of 800 German field guns in their rapid artillery assault on Amiens. Like many of the fields of France, Amiens was left a brown mess destroyed by the horrors of war, but it was here the Germans would have their finest hour. The German offensive was covered in the early morning by a dense fog that lay over the town, providing the cover for a frontal movement of 72 tanks and two divisions. The first German push captured 4000 yards (3,700 meters) of territory ahead of the German lines, and after reaching these objective three more German divisions moved forward under the shield of a creeping barrage. The British desperation was shown in one final attempt to break the German infantry lines with a cavalry charged, which was only mired by the fog. Although the cavalry did reach deep into German holdings in some places, machine gun fire quickly did away with it.

After a six-hour assault the Germans had reached as far in as three miles into British territory, so surprising in some sectors that British officers were captured while eating breakfast. By the end of the day a 15 km gap existed in the British lines, with 13,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers having been taken prisoner. A further 3,500 French were captured in the assault while the German losses remained at only 8,000 in all types. The Germans had lost about two dozen tanks in the assault, but these new weapons of war were seen as having been irrelevant losses. Amiens was captured and five British divisions were lost in the subsequent week-long assault the Germans made to the English Channel. The Germans had finally cut the British and French lines in half, and some German soldiers, exhausted, collapsed at the site of the waters of the Channel. The day was called the "darkest day in the British Army," and it would soon only get darker as the British struggled to find a reason to continue to fight.

In their final push for Paris, 52 German divisions were brought up to the front line on April 25, prepared to strike the decisive blow to end the war. Twenty-three of the divisions attacked the French Fourth Army east of Chantilly, set there to defend in the case of a German breakthrough. Alongside this, the German Seventh and Ninth Armies attack the French stationed to Chantilly's west, as the German commander Ludendorff had wanted to split the French lines in two. The Germans fired their guns for thirteen straight hours, and under the cover of this gunfire the German Sturmtruppen crossed the banks of the River Oisne, preparing for their decisive blow to the French Fourth Army. Eventually the Germans moved three divisions around the Oisne River to attack the French from behind, and the were then supported by the German's main offensive, which slowly, but surely, enveloped the French. Although the French fought valiantly, even being supported by 225 French bombers, who, in a useless effort, risked German controlled skies to bomb the bridges the Germans were using to cross the Oisne, the German captured Chantilly on the morning of April 26. In the end 85,000 French soldiers of the French Fourth Army and their supporting units surrendered after the battle, knocking the entire field army out of the war.

At last having reached their final objective, Paris was now in the German's sights, but then the Germans purposely stalled. They awaited as 15 more German divisions moved up from the reserves to the front line between April 27 and May 4, allowing the French in Paris some time to ready themselves for the coming offense. The German besieged the city beginning on May 5, 1918, surrounding it with 60 Divisions, supported by 700 heavy siege guns and 1,000 field guns. German air power dropped bombs night-and-day on the French lines and in Paris itself in preparation for a main German assault. The German's cut the city's railroads off to ensure that no reinforcements would reach the city and Paris' supply lines were cut, forcing the city to eat what the citizens had within its borders. The Germans had been at the gates of Paris in 1870, and then they had simply starved the city out and defeated multiple break-out attempts. But now the Germans wanted to see the city fall by direct attack, and the German's began their first assault on the city on May 10, 1918.

The Germans decided to best way to do so was in massive waves along the massed Parisian defenses, supported by tanks and air power. The first of such assaults was relatively successful, but at the loss of 5,000 soldiers the Germans had gained just about 1,000 yards, less than a mile, but the city of Paris was still defended by a series of fortresses and redoubts that surrounded its outskirts. The French defenses were centered around the south-east of the city, while the French position much more dense forces of infantry and machine-guns to the north-west where the Seine River flowed, only guarded by one redoubt. But as the Germans had learned how to use heavy artillery to their advantage against French redoubts ar Verdun and Belgian ones at Liege, the Germans decided to attack towards to the south-east. The Germans began to attack the redoubts, one-by-one, on May 20, seizing three redoubts within three days, and opening a gap in the French defenses. But these forts were the second ring of defense around Paris, ones that wee twenty kilometers from Paris itself, they still had more, but older forts, to destroy.

German artillery at that point had only two major forts to break on Paris' southwest side, just 5 kilometers out from the city. The Germans send Sturmtruppen units to raid and take the forts, while Fort Charenton fell rather easily to the German assault, Fort Nogent was a tougher nut to crack. German soldiers failed in a single assault to take the city, but support from German Paris-long range guns made a second assault possible and the fort fell to that attack. A German assault on the line of defense between these two forts required 12 divisions to break, but when it did, Paris was left hopeless. News came to the German command that Paris' defenses had been breached, and Germany sent 10 more divisions into the city to support the original 12 divisions, which pushed to seize the War Ministry, the seats of the French Parliament, and the Eiffel Tower, the symbol of French Republicanism. The French Army was forced to withdraw into the city in order to defend it, opening the door for a massive German onslaught. Two entire field armies attacked the city, finding only modest resistance as the French had retreated to surround the German divisions in the city. As they themselves were surrounded by German soldiers, Erich Ludendorff likened the situation of the French to situation of Caesar at the Battle of Alesia in 52 BCE.

But unlike Caesar, the French would not be breaking out, and the Germans surrounded the French Army, which had now begun to surrender in waves. The French government, besieged and hopeless, finally sued for peace with the Germans, signing the Armistice of Compiegne on June 11, leaving the French people devastated. France was forced to cease all military engagements with the Germans within six hours of the armistice, France was to immediately remove all soldiers from Paris and the Pas de Calais region for the German occupation until the end of the war, the French fleet was to not leave its ports until the war ended, and the French were to surrender all of their railroad access to the German Army. As the French collapsed, the Italians launched their own offensive from May to early June, hoping to gain more of a say in the coming treaty. The French were left with no choice but to accept the armistice, and with this German seemed to have finally reigned victorious over Western Europe, all that was left was Britain and the Netherlands.

The Netherlands was attacked when the German Spring Offensive began in March, as they had only been in the war for several months but German still had a grudge against them for their war 30 years ago. Along with this, German also envisioned the Low Countries as a buffer zone with France in the years to come. Two German Armies, roughly numbering at 450,000 soldiers, backed by 150,000 later soldiers, invaded the Netherlands on March 22, and the Dutch again put up a resistance. The Dutch Army by this point was only at 350,000, just under the 380,000 the Belgian Army had had just years before. The Germans made rapid advances throughout early-to-mid-April as the Dutch Army fell back, allowing the Germans to capture Maastricht, Arnhem, Eindhoven, and Enschede. But the British remained able, despite naval setbacks, to reinforce the Dutch with soldiers, but only about 100,000, that allowed the Dutch to hold out against the Germans into May, when the 150,000 reinforcements arrived. Then into June, as the French fell to the south, the Germans launched a renewed assault on the Dutch, seizing the cities of Rotterdam, Utrecht, and finally Amsterdam. The Dutch surrendered to the Germans on June 20, and the 80,000 British soldiers who hadn't been killed or captured retreated like their counterparts in France across the Channel to defend Britain.

The German Army quickly moved in to occupy Calais, Dunkirk, Amsterdam, and Paris, employing martial law in urban areas until the British were subdued. Superior German naval power was able to put the pressure required on Great Britain, but Ludendorff and Hindenburg also wished for an aerial campaign to reign terror on the British. The German Air Force was determined that once its air fields could be paved down that a rapid campaign of aerial bombardment on London, Bristol, and as far north as Cardiff and Oxford would compliment the naval campaign to starve Britain out. The British public knew that the war had turned against the British favor, but the British Foreign Ministry wished to simply communicate with the Germans and co-ordinate a ceasefire agreement to end British participation. The British would not admit defeat in the war, but the Germans were determined to bring upon them a crippling piece, one of their main purposes for fighting the war was to replace Britain as the premier world power. To the Germans, if Britain were to exit the war as anything less than Germany's subordinate on the world stage then that would be unacceptable.

The Germans began their combined aerial and naval offensive on Britain on August 8, 1918 as evening raids of 20 Zeppelins and 120 bomber aircraft. The German High Seas Fleet moved around the coast of the English Channel, beginning their major blockade of the British Isles. Over the next two weeks the campaign escalated and the Germans began daily night-and-day bombings of southern British cities and the blockade cut Britain off with its strangling grip from their foreign food supply. The Suez Canal was closed to British shipping after the Ottomans seized it in 1917, and by this point the British depended mostly upon food shipments from South America and those Indian ships who could make it around Africa. The United States had shifted most of its agricultural business to Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans, who now required massive shipments of food to support growing populations and to feed expanded armies. But the United States still did ship food to the British, but the Germans did not want to destroy American ships as they though if the United States entered the war it would severely prolong it. They simply blockaded the foreign shipments and forced them to turn their ships around, which angered, but did not provoke foreign nations.

The situation for the British continued to get progressively worse over the next couple of months as rationing harshened, bombings destroyed public offices, and the government of David Lloyd George seemed powerless to stop the German siege. As November opened the German Army began to argue that perhaps only a land invasion of Britain would force them to surrender, but the German General Staff and the Naval Ministry stretched the idea of not wasting any more German lives, especially in what seemed like a war that had already ended. The German Air Force requested permission to begin the bombing of national British landmarks like Westminster Abbey and Number 10 Downing Street, but the General Staff again said no, thinking that such attacks would only serve to galvanize the British populace. So at the beginning November the British Foreign Ministry accepted a communication line with the Germans, who offered them light terms: British shipping lanes would be re-opened, Britain would not be occupied, Britain would not have to have its fleet interred like the French, and the British would be allowed to keep a standing army of 100,000 in the British Isles. The British government agreed to the terms, and an armistice was agreed to on November 11, 1918, finally ending World War I.

Eastern Front

The Eastern Front of World War I began on August 17, 1914 when hostilities were opened between the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires. This front would be unlike the Western Front as it would be almost no-where as nearly as static as the fighting in the West. Although it would not be unlike the Western Front in the end, the aftereffects in the East would be just as repercussive as its Western counterpart in the coming years. Eventually Romania would enter the war too, they themselves would only suffer the same fate as their Russian allies. It would be on the Eastern Front the Germans would have their finest moment in this part of the "War to End All Wars."

1914

The Front opened with the Russian Army going on the offensive and invading East Prussia, a historic home province of the German Empire and core part of Prussia. The opening battle of the offensive was also on August 17 at Stalluponen when the Russian First Army under General Paul of Rennenkampf continued its march to the East Prussian border. von Rennenkampf approached the German defenses around Stalluponen, but was essentially marching unopposed, but for some reason did stop his forces just five miles (8 km) from the German defenses. Then German General Hermann von Francois decided to, without orders, use his I Corps of the Eight German Army to attack a resting Russian division near his defenses. The frontal assault broke the Russian divisions light defenses and they fled eastward, losing 5,000 men and 3,000 soldiers being taken prisoner. Although Francois had then been ordered to cease his pursuit of the Russians, he communicated back that he would so "when he has defeated the Russians." The first battle on the Eastern Front was then turned into a German victory as they broke the Russian Army and began a pursuit.

German commander on the Eastern Front, General Maximilian von Prittwitz, wished to see his German Eight Army keep its defensive position in East Prussia as the Russians heavily outnumbered the Germans. But with the German's successful offensive action at Stalluponen, Francois convinced Prittwitz to launch an offensive action as the German's had better training and equipment than their Russian counterparts. As the German soldiers under Francois were mostly Prussians, and specifically East Prussian, he felt it would be demoralizing to either retreat or be on the defensive while their home fell to the Russians. Prittwitz finally agreed and was given the chance after a skirmish between German and Russian soldiers on August 19 outside the town of Gumbinnen. After this Prittwitz was convinced by Francois to launch a counterattack, and on August 20 the I Corps of the German Eight Army attacked the Russian 28th Division. The Russian artillery launched a counterattack, but quickly used up its ammunition and left the Russians at the mercy of German artillery, which later required them to retreat eight kilometers at the end of the day. German advances further to the south failed after the Russian heavy artillery defeated a German reserve division and the Russian were able to attack the German flanks.

Subsequent German retreats lead to 6,000 prisoners being taken by the Russians, the battle was a near disaster for the Germans and Prittwitz was devastated. Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, the Chief of Staff of the German Military had Prittwitz's recalled and replaced with Paul von Hindenburg. Hindenburg ordered Prittwitz's command of retreating to the Vistula river revoked, and moved to keep the German Army in East Prussia. The Russians suffered from a poor series of supply line, which caused serious problems for the Russian Second Army as it tried to advance. And Paul von Rennenkampf's First Army was delayed after Rennenkampf wanted it to regroup so it could prepare for a possible German counterattack. But the Russians still held a numerical advantage over the Germans, and as the German Eighth Army's position was standing they could not meet the numbers of even most of the Russian Second Army. But Hindenburg believed that the Germans could regain the advantage if only they could move up their reserve corps to the west.

Russian General Samsonov pushed his Army to attack the German XX Corps, which faced encirclement and between 22-24 of August was in a state of skirmish and retreat with the Russians. Samsonov's original objective was the city of Seeburg, but as his flanks were exposed when he advanced he ordered his soldiers to move to the northwest and towards the Vistula. To avoid being flanked Francois was ordered to push towards the Russians' left flank, but Francois said no and waited until August 27 when they would have artillery support. Ludendorff and his deputy, Hoffmann, traveled directly to Francois' Headquarters and ordered him to move against the Russians, which he then promptly agreed to on August 26, ordering his soldiers to charge the enemy with bayonets. Just as General Hoffmann had hoped for, the Russians continued their march to the west and Hoffman had hoped that the further advance of the Russian Second Army would intercept the recently reinforced German lines, allowing for a decisive battle to destroy the Russian Second Army. The battle to come occurred at Allenstein in East Prussia, but would later be named Tannenberg to relate it to the 1410 battle which destroyed the Teutonic Knights.

On the 26th of August, the Russian First Army began its main offensive towards Königsberg and met little resistance along the way. As they moved, they hoped to expose the Second Army's right flank and open a gap between the two armies, which was then reported on by the Russians and intercepted by the Germans. The German XVII Corps began the German attack by fighting the divided Russian VI Corps, which had been divided up into its two divisions. The Corps retreated and the right flank of the Second Russian Army was now open for the German offensive. The Russians were then blocked from a further advance to the south by the German XX Corps, but the center of the Russian advance continued unopposed. Francois lead an attack on the Russian left flank on August 27, which was defended by the Russian I Corps, in which his artillery proved decisive and the Corps was retreating by nightfall. Samsonov ordered his advancing XIII Corps to cease movement while the Russian XII and XV were trapped with the XIII corps in the Tannenberg area. By the end of August 28, the Russian I and VI Corps were retreating and the Russian Second Army's left and right flanks were left exposed.

Rennenkampf was ordered back from the advance to Königsberg to assist the trapped Second Army and the XVII Corps moved southwest to assist the Second Army. But by August 29 the Second Army was trapped and being bombarded daily by German artillery, leaving them nearly hopeless. The Russian First Army attempted to assist the trapped Second Army, but they were delayed by German cavalry. By the end of August 29, the Russian First Army's XVII and VI Corps were still 70 kilometers from the Second Russian Army and the First Army was now stretched out and scattered, leaving the entire Russian advance in a very dangerous position. By the end of August 30, the battle was over and the Second Russian Army was completely destroyed: 78,000 killed or wounded, 92,000 captured and 500 guns seized by the Germans. The First Russian Army was still in danger, however, and the Germans were ready to exploit this and finally stop the Russian invasion of East Prussia. When the news of the Second Army's destruction reached him, General Alexander Samsonov committed suicide.

The remains of the Second Russian Army were gone by September 2, and the German Army was moved to meet the Russian First Army under Rennenkampf's command. The right flank in the north was under the protection of extensive defense works outside of Königsberg, but the Germans were able to reinforce for the attack by providing two new corps to the Eight German Army. Rennenkampf moved his new forces to the northern defenses and prepared the First Army for a counter-offensive to the south. Ludendorff moved two corps to the south to defend the area around the Masurian Lakes and covered any gaps along his lines during this time. Then the 3rd Reserve Division was moved 30 miles south from Rennenkampf's lines to provide for a secure defense in the case of a Russian attack to the south. But then Ludendorff ordered his soldiers in the south to attack the Russians before they could attack him on September 7th. The Germans then pressed the defensive northern flank of the First Russian Army, bombarding them with their artillery. The Russians in the north retreated in good order, but to the south the Russian II Corps was being attacked by both the XVII and I Corps.

The Russian II Corps fell back to the south and Rennenkampf ordered his northern forces to push the German XX Corps back, which they only slightly succeeded in doing. But eventually the Russian II Corps was itself forced to fall back because otherwise it would have been surrounded by the Germans. By September 11, the Russians retreated to the north, but news was now developing in Russia's HQ that encirclement appeared possible. As Rennenkampf wished to avoid the same fate as Samsonov he ordered a retreat by the First Army to the Russian border. A strong rear guard allowed the Russian retreat to occur rapidly, but Ludendorff had succeeded in setting up a trap but news of a possible Russian counterattack stopped the Germans and their advance stalled. The Russian First Army suffered 170,000 casualties, 125,000 killed or wounded and 45,000 captured, the First and Second Russian Armies were destroyed, but General Paul von Rennenkampf managed to survive the struggle. The Russian Tenth Army waited for the retreating Russians at their border and the Germans were forced to cease their advance, but the Central Powers were not finished yet.

By August 26, the Austro-Hungarian Army and its highest commander, Chief of the General Staff Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, were ready for a Central Powers offensive into Russian Poland. But as the Germans were busy fighting and destroying two Russian field armies off to the north, they were convinced otherwise and the Austro-Hungarians prepared for the Russian defeat in East Prussia before launching an offensive into Poland with Germany. By mid-September, September 13 to be exact, the Austro-Hungarians and Germans were ready, but Hötzendorf had worried that if they didn't act rapidly that Russia's numbers could be brought to bear against the Central Powers. First the Austro-Hungarians attack Krasnik, attacking with superior numbers and a better physical position. The Austro-Hungarians also possessed superior cavalry, which was on the Eastern Front a great advantage with mobile warfare. The Russian Chief of Staff, General Mikhail Alexeyev ordered the Fourth and Fifth Russian Armies to stand their ground against any Austro-Hungarian attack, dooming these two armies. The Austro-Hungarians attack on September 23, using their cavalry in a flanking attack on the Russian Fourth army and a frontal infantry assault backed by artillery to destroy the Russians. The Russian Fourth Army was demolished and many soldiers were taken prisoner, the Austro-Hungarian had begun to gain momentum.